Over a decade has passed since the Institute of Medicine’s reports on the need to improve the American healthcare system, and yet only slight improvement in quality and safety has been reported. The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) initiative was developed to integrate quality and safety competencies into nursing education. The current challenge is for nurses to move beyond the application of QSEN competencies to individual patients and families and incorporate systems thinking in quality and safety education and healthcare delivery. This article provides a history of QSEN and proposes a framework in which systems thinking is a critical aspect in the application of the QSEN competencies. We provide examples of how using this framework expands nursing focus from individual care to care of the system and propose ways to teach and measure systems thinking. The conclusion calls for movement from personal effort and individual care to a focus on care of the system that will accelerate improvement of healthcare quality and safety.

Key words: QSEN, quality, safety, systems, QSEN competencies, education, measurement

...national healthcare quality organizations, such as the Leapfrog Group, report that the majority of hospitals have demonstrated little progress in improving quality and safety.Over a decade has passed since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, and the follow-up report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, which turned healthcare professionals’ attention to the importance of improving healthcare outcomes (IOM, 2000; Committee on the Quality, 2001). These reports highlighted the need to redesign systems of care to better serve patients in the complex healthcare environment. During the last decade, national initiatives to improve quality and safety have been implemented, such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) Transforming Care at the Bedside, 5 Million Lives Campaign, and the Triple Aim (IHI, 2013a; IHI, 2013b; IHI, 2013c). To accelerate change, regulatory agencies have implemented National Patient Safety Goals, Core Measures, (Joint Commission, 2013a; 2013b; 2013c), and Hospital Acquired Conditions (HAC) Never Events (Kuhn, 2008). Yet national healthcare quality organizations, such as the Leapfrog Group, report that the majority of hospitals have demonstrated little progress in improving quality and safety. For example, although we know that zero central line infections should be a reality in hospitals, thousands of infections are still reported each year (Clark, 2013).

QSEN is a national movement that guides nurses to redesign the ‘what and how’ they deliver nursing care so that they can ensure high-quality, safe care. In 2005, nursing leaders responded to the IOM call to improve the quality of healthcare by forming the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) initiative funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The QSEN initiative consisted of the development of quality and safety competencies that serve as a resource for nursing faculty to integrate contemporary quality and safety content into nursing education (QSEN Institute, 2013). The focus of QSEN, now the QSEN Institute, has expanded from undergraduate nursing students’ education to include quality and safety education for all nurses. The mission of QSEN is to address the challenge of assuring that nurses have the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSA) necessary to continuously improve the quality and safety of the healthcare systems in which they work. QSEN is a national movement that guides nurses to redesign the ‘what and how’ they deliver nursing care so that they can ensure high-quality, safe care. Linda Cronenwett, PhD, RN, FAAN, the founder of QSEN, often states that QSEN helps nurses to identify and bridge the gaps between what is and what should be and helps nurses focus their work from the lens of quality and safety (Personal Communication, 2013).

Viewing nurses’ work through the lens of quality and safety requires a contemporary approach that incorporates systems thinking. A crucial skill, systems thinking helps nurses to meet the challenge of improving healthcare as they move beyond the application of the QSEN competencies from individual patients and families to accelerate the overall improvement of healthcare quality and safety. In this article, we review the history of QSEN and propose a framework that expands nursing focus from individual care based on personal effort and care of the individual to systems thinking and care of the system. Examples are provided to demonstrate how to integrate systems thinking in the application of QSEN competencies and how systems thinking can be taught and measured.

QSEN History

Although QSEN competencies have spurred quality and safety in nursing education, it is now time to accelerate their use and impact. In response to calls for improved quality and safety, leaders from schools of nursing across the country joined forces to create the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) initiative. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in 2005 funded QSEN Phase 1 and three subsequent phases followed (Table 1). The major QSEN contribution to healthcare education was the creation of six QSEN competencies (modeled after the IOM reports) and the pre-licensure and graduate-level knowledge, skills, and attitude (KSA) statements for each competency (Cronenwett et al., 2007). The competency statements provide a tool for faculty and staff development educators to identify gaps in curriculum so that changes to incorporate quality and safety education can be made (Barnsteiner et al., 2013). The QSEN website serves as a national educational resource and a repository for nurses to publish contemporary teaching strategies focused on the six competencies: patient-centered care, teamwork and collaboration, evidenced-based practice, quality improvement, and informatics. Currently, there are over 100 teaching strategies posted.

|

Phase |

Details |

Websites and References |

|

Phase 1a October 2005-March 2007 |

QSEN competencies and their requisite KSAs QSEN.org website |

qsen.org/competencies/pre-licensure-ksas/ |

|

Phase 2a April 2007–October 2008 |

Funded 15 pilot schools to use the IHI Learning Collaborative method to develop, test, and disseminate teaching strategies Peer reviewed teaching strategies on the website |

|

|

Phase 3a November 2008-February 2012 |

National forums to educate nursing faculty Incorporation of nurses into the Veterans Affairs (VA) Quality Scholars program (VAQS- 2 year pre or post-doctoral fellowships in quality and safety) Faculty modules to the QSEN website 8 regional Faculty Development workshops (train the trainer) were coordinated by the AACN |

|

|

Phase 4a March 2012-March 2014 |

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) funded to further develop graduate competencies and coordinate 5 graduate level faculty development conferences |

|

|

San Francisco Bay Area (SFBA) QSEN Faculty Development Instituteb 2009-2013 |

AACN implementation and evaluation of impact of incorporating the QSEN content into 22 schools of nursing in the San Francisco Bay area. Funding for a series of workshops for faculty and clinical leaders |

|

|

Academic/Clinical Partnership and collaboration in QSEN Lourdes University and ProMedicac |

Innovative educational model for undergraduate education that includes a clinical integration partner to assist with the QSEN-based clinical education model |

|

|

QSEN Institute July 2012 to present |

The Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at Case Western Reserve University continues to host the website and the National QSEN forum |

|

|

aRobert Wood Johnson Foundation funding |

||

QSEN competencies have been used by national nursing organizations and are the central focus of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (n.d.) Nurse Residency program, the foundational concepts in the Massachusetts Future of Nursing Framework (Massachusetts Department of Higher Education, 2010), and the Ohio Hospital Association (Ohio Organization of Nurse Executives, 2013). The QSEN competencies also have been incorporated into nursing textbooks such as the medical-surgical text by Ignatavicious and Workman (2013), and other books, such as Quality and Safety in Nursing: A Competency Approach to Improving Outcomes (Sherwood & Barnsteiner, 2012), Second Generation QSEN, a special issue of the Nursing Clinics of North America (Barnsteiner & Disch, 2012) and Quality and Safety for Transformational Leadership (Amer, 2012).

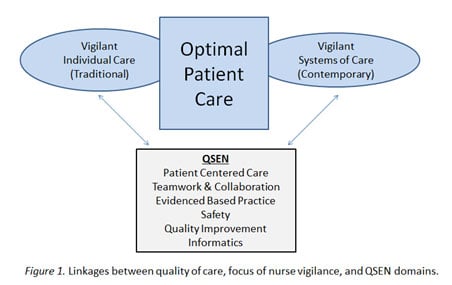

Systems Thinking

Although QSEN competencies have spurred quality and safety in nursing education, it is now time to accelerate their use and impact. The full effect of the QSEN competencies to improve the quality and safety of care can only be realized when nurses apply them at both the individual and system levels of care. Many nurse educators report that the QSEN competencies are already integrated into their curriculum, but in our practice, we have noted that often this integration is at the individual level of care, rather than at the level of the system of care. The full effect of the QSEN competencies to improve the quality and safety of care can only be realized when nurses apply them at both the individual and system levels of care. Figure 1 provides a display of how the six QSEN domains are linked to optimal patient care through both vigilant individual care and vigilant systems of care. Traditionally, nurses have focused primarily on vigilant individual care; less attention has been given to assisting nurses to provide vigilant systems of care. We propose that in addition to the emphasis on teaching critical thinking skills (Simpson & Courtney, 2002), nurses also need to be taught the knowledge and skills associated with systems thinking. In their day-to-day work, nurses’ abilities to engage in better problem-solving, priority setting, delegation, interactions and collaborations, decision making, and action-taking are greatly influenced by their ability to view how any one component of their work system is related to other components and to the whole.

|

| Figure 1 Source: Authors |

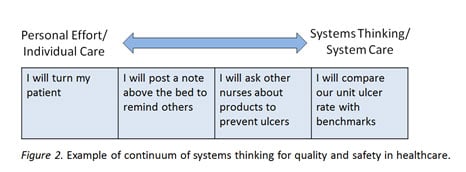

Systems thinking is the ability to recognize, understand, and synthesize the interactions and interdependencies in a set of components designed for a specific purpose. This strategy includes the ability to recognize patterns and repetitions in interactions and an understanding of how actions and components can reinforce or counteract each other. These relationships and patterns occur at different dimensions: temporal, spatial, social, technical or cultural (Oshry, 2007). Systems thinking links a person’s environment to his/her behavior. In the delivery of nursing care, this involves the nurse’s understanding and valuing how components of a complex healthcare system influence care of an individual patient. Systems thinking can be viewed as a continuum, ranging from the individual to the larger internal and external environmental components. Figure 2 shows examples of care approaches that represent increasing levels of systems thinking.

|

| Figure 2 Source: Authors |

Systems thinking links a person’s environment to his/her behavior. How nurses view both themselves as nurses, and their work, is shaped by the structures and processes of the systems in which they work. Most nurses provide care in healthcare organizations that are characterized as complex, multilevel, and multifunctional. Greater knowledge and application of systems thinking skills by nurses have the potential to mitigate errors in practice, improve nurse priority setting and delegation, enhance problem solving and decision-making, improve timing and quality of interactions with other professionals and patients, and enhance workplace quality improvement initiatives. The ability to engage in systems thinking has been viewed as a key component in the successful delivery of safe and high quality care (Bataldan & Mohr, 1997; Bataldan & Leach, 2009; Batalden & Stoltz, 1993; Senge, 2006). Systems thinking is required to redesign healthcare to improve the quality and safety of care.

The importance of systems thinking in quality improvement (QI) initiatives was identified in early literature on application of QI techniques to healthcare (Batalden & Stoltz, 1993; Deeming & Appleby, 2000) and, more recently, was highlighted in reports from the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2003), the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (Varkey, Karlapudi, Rose, Nelson, & Warner, 2009), and the article, “Quality and Safety Education for Nurses” (Cronenwett, Sherwood & Barnsteiner, 2007). Given the hypothesized importance of systems thinking in the success of quality and safety in healthcare, it is probable that if nurses engage in better systems thinking, greater improvements in outcomes will be achieved. Knowledge and skills associated with systems thinking, however, are seldom addressed in basic or continuing nursing education. The next sections describe strategies for teaching and learning systems thinking, especially as related to QSEN competencies, and a newly developed tool for measurement of systems thinking.

Teaching and Learning Systems Thinking

Systems thinking is an essential skill for nurses. Yet, there has been little knowledge disseminated about how to assist nurses to better engage in this type of thought process, despite their key roles in planning, delivering, and improving patient care in complex organizations. To teach systems thinking it is important to enhance the learner’s awareness of the interdependencies in people, processes, and services and to view problems as occurring as part of a chain of events of a larger system, rather than as independent events.

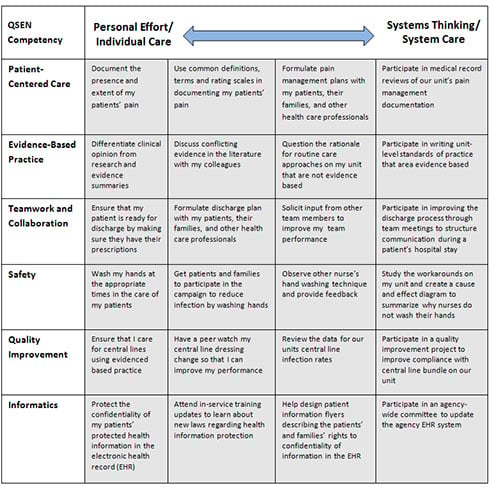

The clinical environment is an ideal place to teach systems thinking in undergraduate, graduate, and staff development education. During the clinical experience, the faculty preceptor can broaden the learner’s problem identification from a focus on personal effort in a single situation to a focus on sequences of events with possible multiple causes for both individuals and populations. Table 2 provides examples of this continuum of systems thinking using the QSEN competencies. An example of a teaching technique for systems thinking is to have learners create grids such as those presented in Table 2 to expand their scope of thinking from the individual to the system level of care. Students might obtain outcome data from their unit and identify reasons for variation across time. Enhancing systems thinking skills also can be done by having learners complete an assessment of their unit or microsystem.

Assessment tools are available from the Clinical Microsystem (2013) Green Books for inpatient, emergency room, long-term care, and outpatient groups. These free workbooks from the Dartmouth Institute have been developed to help individuals assess the complexity of the system in which they work. Another approach to expand learners’ scope of thinking to a systems level is to have them connect nursing skills and clinical issues to national quality and safety initiatives (Armstrong & Barton, 2013). For example, urinary care is connected to the National Quality Forum (2012) Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) prevention and the Joint Commission’s (2013c) National Patient Safety Goal Number 7.

| Table 2. Examples of Continuums of Systems Thinking for QSEN Domains |

|

| View Table 2 [pdf] |

Nurses can also learn systems thinking by creating flowcharts or process diagrams that elicit the steps of a care process and the multitude of healthcare workers involved in that process. This mapping technique is one of the first steps of a quality improvement project. For example, to improve the care coordination of preparing hospitalized patients for discharge, teams of healthcare professionals could map steps in the course of a patient’s stay leading to discharge. This exercise has been shown to increase knowledge about system factors and enhance awareness of the importance of interprofessional collaboration (Brennen, Olds, Dolansky, Estrada, & Patrician, in press).

Another approach to teach systems thinking is to have learners conduct a root cause analysis (Lambton & Mahlmeister, 2010; Tschannen & Aebersold, 2010). Root cause analysis (RCA) is a widely used technique to assist people to move beyond blame of an individual for errors made in the workplace to understanding the system factors that may have contributed to errors. Healthcare organizations routinely perform RCA after an event so that appropriate changes can be made in the system to prevent future errors. This technique could be used to understand system factors even when events “almost happen.” Having nursing students participate in RCAs during their undergraduate education has been shown to be beneficial (Dolansky, Druschel, Helba, & Courtney, 2013). For example, having students conduct an RCA for addressing a medication error may lend a new perspective to how system level factors interact with individual level factors in the creation of that error.

In the classroom setting, systems thinking also can be enhanced by using case studies. The book Set Phasers to Stun (Casey, 1998) includes stories of design, technology, and human error that can be discussed in class. These stories identify the close connection between technology and humans. Another book, Systems Concepts in Action (Williams & Hummelbrunner, 2011), is a practitioner’s toolkit to teach the principles of systems thinking, such as system dynamics, outcome mapping, and social network analysis. Highly effective and very interactive, the game Friday Night in the ER (2009) guarantees learning and fun. The game is played by four people and simulates the challenge of managing a hospital during a 24-hour period. Each player is in charge of a unit. The demands of the game demonstrate that systems thinking is the key to success.

Lastly, teaching systems thinking requires guided reflection. Faculty need to assist learners to look for and recognize patterns in systems of care by standing back, reflecting on data, and considering the system as a whole. Too often in healthcare we make quick judgments that are based on limited information and preconceived ideas. Teaching nurses to step back and consider the dependencies and interconnectedness of system components will lead to a broader understanding of the healthcare system and the quality of care that results from that system.

Measurement of Systems Thinking

To improve systems thinking, we need to be able to measure it. A valid and reliable measure of systems thinking is now available. The Systems Thinking Scale (STS) is an instrument that measures healthcare professionals’ systems thinking specifically related to system interdependencies. The 20-item STS has good reliability as demonstrated by a test-retest reliability assessment (N=36; correlation of .74) and internal consistency testing (N=342) using Cronbach’s alpha (.89) (Case Western Reserve University, 2013b).

...systems thinking can be taught and learned and an individual’s level of systems thinking can be changed. Data from recent studies indicated that systems thinking can be taught and learned and an individual’s level of systems thinking can be changed (Abourmatar et al., 2012; Moore, Dolansky, Palmieri, Singh, & Alemi, 2010). Moore and colleagues tested three groups of healthcare professions students (n= 102) who received high, low, or no dose levels of systems thinking education. There were no differences in STS mean scores at pretest. At posttest, the high-dose systems thinking education group scored significantly higher on the STS than both the low and no-dose groups (p=.05 and .01, respectively). The STS is now publicly available for use and a website has been established to provide information on its use (Case Western Reserve University, 2013a).

Conclusion

Almost 10 years have passed since the QSEN competencies were developed, and the field of quality and safety is rapidly advancing. The time has come to consider what new competencies should be added. We propose that the current QSEN competencies and knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) be reviewed and evaluated. Do the KSAs need to be updated, reclassified, or expanded? Should a systems perspective be made more prominent in the QSEN model? The QSEN competencies were developed to be a tool to promote better education for nurses in healthcare quality and safety. We need to update the QSEN competencies to be as useful as possible to prepare all nurses to ensure the highest level of care possible.

... a safe and high quality system of care requires that all healthcare professionals take responsibility to learn and apply skills associated with improving the wider system of care. Throughout QSEN history, reports from nurses and nurse faculty are that they already integrate the QSEN competencies into education and practice. However, we have observed that, despite the fact that contemporary approaches to quality and safety emphasize a systems view, much of the nursing education approach to teaching quality and safety (including application of the QSEN competencies) emphasizes personal effort at the individual level of care. Although we believe that personal expertise of the nurse with individual patients is necessary, a safe and high quality system of care requires that all healthcare professionals take responsibility to learn and apply skills associated with improving the wider system of care. We argue, therefore, that the QSEN competencies should be integrated into nursing curriculum and practice with a strong systems-perspective emphasis. Nurse faculty and staff development educators must critically evaluate the extent to which they apply QSEN competencies and at what levels.

Authors

Mary A. Dolansky, PhD, RN

Email: mad15@case.edu

Mary A. Dolansky is an Associate Professor at the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH. Dr. Dolansky is Director of the QSEN Institute (Quality and Safety Education for Nurses) and Senior Fellow in the VA Quality Scholars program, mentoring pre- and post-doctoral students in quality and safety science. She has co-published two books on quality improvement, co-authored several book chapters and articles, and was guest editor on a special quality improvement education issue in the Journal of Quality Management in Health Care. She has taught the interdisciplinary course, “Continual Improvement in Health Care,” at CWRU for the past 8 years and was chair of the quality and safety task force at the School of Nursing that integrated quality and safety into the undergraduate and graduate curriculum.

Shirley M. Moore, PhD, RN, FAAN

Email: smm8@case.edu

Shirley M. Moore is the Edward J. and Louise Mellon Professor of Nursing and Associate Dean for Research, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH. She is a past President of the Academy for Healthcare Improvement and is on the leadership team of the national Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project. She is currently leading the integration of nurse scholars in the VA Quality Scholars Program. She also is conducting NIH-funded studies testing a process improvement approach to health behavior change with patients.

References

Abourmatoar, H.J., Thompson, D., Wu, A., Dawson, P., Colbert, J., Marsteller, J., & Pronovost, P. (2012). Development and evaluation of a 3-day patient safety curriculum to advance knowledge, self-efficacy and system thinking among medical students. BMJ Quality and Safety. 21(5). Doi.org/10.1136/bmj qs-2011-000463.

Amer, K. (2012). Quality and safety for transformational nursing. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. Pearson Publishing.

Armstrong, G. & Barton, A. (2013). Fundamentally updating fundamentals. Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(2), 82-87. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.12.006

Barnsteiner, J., Disch, J., Johnson, J., McGuinn, K., Chappell, K., & Swartwout, E. (2013). Diffusing QSEN competencies across schools of nursing: The AACN/RWJF Faculty Development Institutes. Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(2) 68-74. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.12.003

Batalden, P.B., & Leach, D.C. (2009). Sharpening the focus on systems-based practice. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 1, 1-3. doi: 10.4300/01.01.0001

Batalden, P.B., & Mohr, J.J. (1997). Building knowledge of health care as a system.Quality Management in Health Care, 5, 1-12.

Batalden, P.B. & Stoltz, P.K. (1993). A framework for the continual improvement of health care: Building and applying professional and improvement knowledge to test changes in daily work. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement,19, 424-447.

Brennan, C., Olds, D., Patrician, P. A., Dolansky, M. A., & Estrada, C. (in press). Learning by doing: Observing an interprofessional process as an interprofessional team. Journal of Interprofessional Care.

Case Western Reserve University, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing. (2013a). Systems thinking scale manual. Retrieved from http://fpb.case.edu/systemsthinking/manual.shtm

Case Western Reserve University, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing. (2013b). The systems thinking scale: A measure of systems thinking. Retrieved from http://fpb.case.edu/systemsthinking/index.shtm

Casey, S. M. (1998). Set phasers on stun: And other true tales of design, technology, and human errors (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: Aegean.

Clark, C. (2013) Leapfrog hospital safety scores ‘depressing.’ HealthLeaders Media. Retrieved from www.healthleadersmedia.com/page-1/QUA-292000/Leapfrog-Hospital-Safety-Scores-Depressing

Clinical Microsystems.(2013). Materials overview. Retrieved from www.clinicalmicrosystem.org/materials/materials_overview/

Committee on the Quality of Health Care in America. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Cronenwett, L., Sherwood, G., Barnsteiner, J., Disch, J., Johnson, J., Mitchell, P., & Warren, J. (2007). Quality and safety education for nurses. Nursing Outlook, 55, 122-131.

Deeming, C. & Appleby, J. (2000). Measuring performance. Green with envy?. Health Service Journal, 110, 22-25.

Didion, J., Kozy, M. A., Koffel, C., & Oneail, K. (2013). Academic/Clinical partnership and collaboration in Quality and Safety Education for Nurses education. Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(2) 88-94. doi: 10.1016/j.profjurs.2012.12.004

Disch, J., Barnsteiner, J., & McGuinn, K. (2013). Taking a “deep dive” on integrating QSEN content in San Francisco Bay Area schools of nursing. Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(2), 75-81. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.12.007

Dolansky, M.A., Helba, M., Druschel, K., & Courtney, K. (2012). Nursing student medication errors: A root cause analysis to develop a fair and just culture. Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(2), 102-108. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.12.010

Estrada, C.A., Dolansky, M.A., Singh, M.K., Oliver, B.J., Callaway-Lane, C., Splaine, M., & Patrician, P.A. (2012). Mastering improvement science skills in the new era of quality and safety: The Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Program. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18, 508-514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.1816.x.Epub 2012 Feb 5

Friday night at the ER. (2009). Retrieved from: www.fridaynightattheer.com/

Ignatavicious, D. D., & Workman, L. M. (2013). Medical- Surgical nursing patient-centered collaborative care. (7th Edition). Philadelphia: PA: Elsevier.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2013a). IHI triple aim initiative. Retrieved from www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2013b). Protecting 5 million lives from harm. Retrieved from www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/PastStrategicInitiatives/5MillionLivesCampaign/Pages/default.aspx

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2013c). Transforming care at the bedside. Retrieved from www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/PastStrategicInitiatives/TCAB/Pages/default.aspx

Institute of Medicine (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2003). Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Joint Commission. (2013a). Core measure sets. Retrieved from www.jointcommission.org/core_measure_sets.aspx

Joint Commission. (2013b). Hospital: 2013 national patient safety goals. Retrieved from www.jointcommission.org/hap_2013_npsg/

Joint Commission. (2013c). National patient safety goals. Retrieved from www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx

Kuhn, H. B. (2008). State medicaid director letter. Retrieved from http://downloads.cms.gov/cmsgov/archived-downloads/SMDL/downloads/SMD073108.pdf

Lambton, J., & Mahlmeister, L. (2010). Conducting root cause analysis with nursing students: Best practice in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 49, 444-448. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20100430-03

Massachusetts Department of Higher Education. (2010). Creativity and connections: Building the framework for the future of nursing education and practice. Retrieved from www.mass.edu/currentinit/documents/NursingCoreCompetencies.pdf

Moore, S.M., Dolansky, M.A., Palmieri, P., Singh, M., & Alemi, F. (2010). Developing a measure of system thinking: A key component in the advancement of the science of QI. International Health Forum on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, Nice, France: Acropolis.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (n.d.). Transition to practice regulatory model. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/TransitiontoPracticeFinalModel.pdf

National Quality Forum. (2012). Endorsement summary: Patient safety measures. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CDMQrAIwAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.qualityforum.org%2FWorkArea%2Flinkit.aspx%3FLinkIdentifier%3Did%26ItemID%3D69827&ei=VG8sUuqDOZDiyAHBlYDAAg&usg=AFQjCNE_qJ9BZSyI63f9avYGUXrfAbdhxA&sig2=xFAgr-SmYYONPVLUS1A3iw&bvm=bv.51773540,d.aWc

Ohio Organization of Nurse Executives. (2013). Position statement: Quality and safety education for nursing. Retrieved from www.ohanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/QSEN-White-Paper-3.21.13.pdf

Oshry, B. (2007). Seeing systems: Unlocking the mysteries of organizational life. San Fransico: Barett-Koehler.

Patrician, P. A., Dolansky, M. A., Pair, V., Bates, M., Moore, S.M., Splaine, M., & Gilman, S. C. (2012). The Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars (VAQS) Program: A model for interprofessional education in quality and safety. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(1), 24-32. doi:

Patrician, P. A., Dolansky, M. A., Estrada, C., Brennan, C., Miltner, R., Newsom, J., … Moore, S. M. (2012). Interprofessional education in action: The VA Quality Scholars Fellowship program. Nursing Clinics of North America, 47, 347-354.

QSEN Institute. (2013). Competencies. Retrieved from http://qsen.org/competencies/

Senge, P.M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organizations. New York: Doubleday.

Sherwood, G. & Barnsteiner, J. (2012). Quality and safety in nursing: A competency approach to improving outcomes. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Simpson, E. & Courtney, M. (2002). Critical thinking in nursing education: Literature review. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 8, 89-98.

Tschannen, D., & Aebersold, M. (2010). Improving student critical thinking skills through a root cause analysis pilot project. Journal of Nursing Education, 49, 478-485. doi: 10.3928-01484834-20100524-02

Varkey, P., Karlapudi, S., Rose, S., Nelson, R., & Warner, M. (2009). A systems approach for implementing practice-based learning and improvement and systems-based practice in graduate medical education. Academic Medicine, 84, 335-339. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819731fb

Williams, B. & Hummelbrunner, R. (2011). Systems concepts in action: A practitioner’s toolkit. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.