Discrimination due to gender, race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and socio-economic status negatively impacts health of these US populations. Implicit bias impacts the patient-provider relationship and healthcare outcomes. Efforts are ongoing to define implicit bias (IB), identify affected populations, and evaluate provider understanding of IB and its effect on patient care. Nurse leaders are in a unique position to address these issues through policy development. This review analyzes National Nursing Organizations’(NNO) availability of policies and clinical resources on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) to engage, educate, and equip nurses to deliver patient-centered, culturally responsive care and to effectively recognize and respond to implicit bias in healthcare settings.

Key Words: systemic racism, health disparities, diversity policy, DEI policy, diversity and equity training, DEI position statement, implicit bias, national nursing organizations

Healthcare discrimination related to gender, race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and socio-economic status negatively impacts health of these populations. Current research examining healthcare provider implicit bias highlights how providers, directly and indirectly, contribute to this problem (Gatewood, Broholm, Herman, & Yingling, 2019; Maxfield et al., 2020; Chatterjee et al., 2020). Education efforts for healthcare providers offering approaches to reduce inequalities and interrupt systemic elements that contribute to poor patient outcomes are needed (ANA, 2019; Effland & Hays, 2018)

National nursing organizations (NNOs) work to increase awareness of healthcare discrimination related to gender, socioeconomic status (SES), race and ethnicity, and other forms of bias through focused policy and education efforts (AACN, 2017; ACMN, n.d.; ANA, 2019). Moreover, NNOs influence health policy through innovative leadership and policy development. Establishing a policy agenda, setting directed decision-making guidelines, and initiating collaborative partnerships and networks demonstrate the potential for successful NNO policy initiatives (Chiu, Duncan, & Whyte, 2020). Nurse leaders are able to successfully influence health policy (O’Rourke, Crawford, Morris, & Pulcini, 2017). Nurse-developed frameworks such as the Policy Circle Model have demonstrated efficacy in engaging nurses through NNOs to respond to health threats rapidly and effectively through policy-focused education and initiatives (Peck, 2022). This review analyzes NNOs’ availability of policies and clinical resources on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) to engage, educate, and equip nurses to deliver patient-centered, culturally responsive care and to effectively recognize and respond to implicit bias in healthcare settings.

Background

Implicit bias (IB) refers to lack of awareness of unconscious bias or attitudes which are difficult to acknowledge and control Implicit bias (IB) refers to lack of awareness of unconscious bias or attitudes which are difficult to acknowledge and control (Hall, et al., 2015). For this analysis, implicit and unconscious bias are used synonymously, and “bias” refers to IB. IB includes, but is not limited to, racial and ethnicity, SES, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and weight bias (Hall et al., 2015).

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) (2003) Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare report highlighted the issue of bias demonstrated by providers and its contribution to differential treatment, elevating the issue to the national stage (Smedley et al., 2003; Dehon et al., 2017). In a review of over 100 studies conducted by the IOM and commissioned by Congress, findings indicate healthcare providers exhibit bias, prejudice, and stereotyping of patients resulting in discriminatory care and treatment (IOM, 2003; Dehon et al., 2017). Ten years later, the 2012 National Healthcare Disparities report revealed that discrepancies in treatment continued to exist across populations of color. Black patients received lower-quality care than White patients for 40% of the identified quality measures (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2013; Dehon et al., 2017).

Data from the IOM report provides a historical reference and future guide as researchers continue to investigate correlations between healthcare providers and educators’ behaviors and biases to adverse patient outcomes in clinical settings (Gatewood et al., 2019). Multiple studies report higher implicit racial bias (IRB) with people of color in healthcare settings (Blair et al., 2013; Hagiwara, Elston Lafata, Mezuk, Vrana, & Fetters, 2019; Gatewood et al., 2019; Maina, Belton, Ginzberg, Singh, & Johnson, 2018; & Oliver, Wells, Joy-Gaba, Hawkins, & Noek, 2014). A review that examined associations between IB and healthcare outcomes concluded that lower communication skills and perceptions of noncompliance in people of color were associated with provider IB assessment results of preferences for White patients (Maina et al., 2018). Furthermore, persons applying to medical school reported gender, age, race, national origin, religion, and sexual orientation as sources of discrimination, and 35% reported experiencing bias at more than one school using the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) (Chatterjee et al., 2020). Participants reporting bias had completed more interviews (5.2 vs. 3.9) and were more likely to be Latino (30.6% vs. 16.4%, P<.05) than those who did not report bias (Chatterjee et al., 2020). These findings suggest that IB is present in healthcare education in addition to clinical settings.

Minimal nursing research exists on the topic of IB. Studies of other healthcare disciplines provide insight into the problem of provider implicit bias (Blair et al., 2013; Oliver et al., 2014; van Ryn et al., 2015; Maxfield et al., 2020; Chatterjee et al., 2020). Most published work on IB by nurses does not focus on policy direction to address IB or espouse a standardized nursing position (Gatewood et al., 2019). This is significant because although a few NNOs have created position statements or policies addressing racism, discrimination, or diversity, none are universally adopted as a policy standard across the nursing profession. Additionally, IB training is not a requirement in nursing education curricula or for nursing educators, which may lead to bias in nursing education similar to what is experienced in medical education (AACN, 2006; 2008; 2011; Gatewood et al., 2019). Without definitive evidence-informed policy recommendations specific to nurses, the profession will lack policy and direction related to removing bias in education and clinical practice.

Method

Conceptual Framework

A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis provides the framework for this analysis A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis provides the framework for this analysis (Bardach & Patashnik, 2020). The model takes a commonsense, step-by-step approach that removes complexity and creates a robust policy analysis to assist novice practicing analysts or introduce graduate students new to policy analysis. Bardach’s guide follows an eightfold path through a problem-solving procedure that provides practical examples for each section: Define the Problem, Assemble Some Evidence, Construct the Alternatives, Select the Criteria, Project the Outcomes, Confront the Trade Offs, Stop, Focus, Narrow, Deepen, Decide!, and Tell Your Story (Bardach & Patashnik, 2020). The framework incorporates adjunctive resources, such as the CDC’s Policy Analytical Framework (Bardach & Patashnik, 2020). The policy analysis framework guided this investigation of NNO’s policy efforts to respond to the challenges of fostering a diverse nursing workforce and helping nurses care for an increasingly diverse population while addressing the effects of IB on health outcomes and disparities.

Survey Procedures

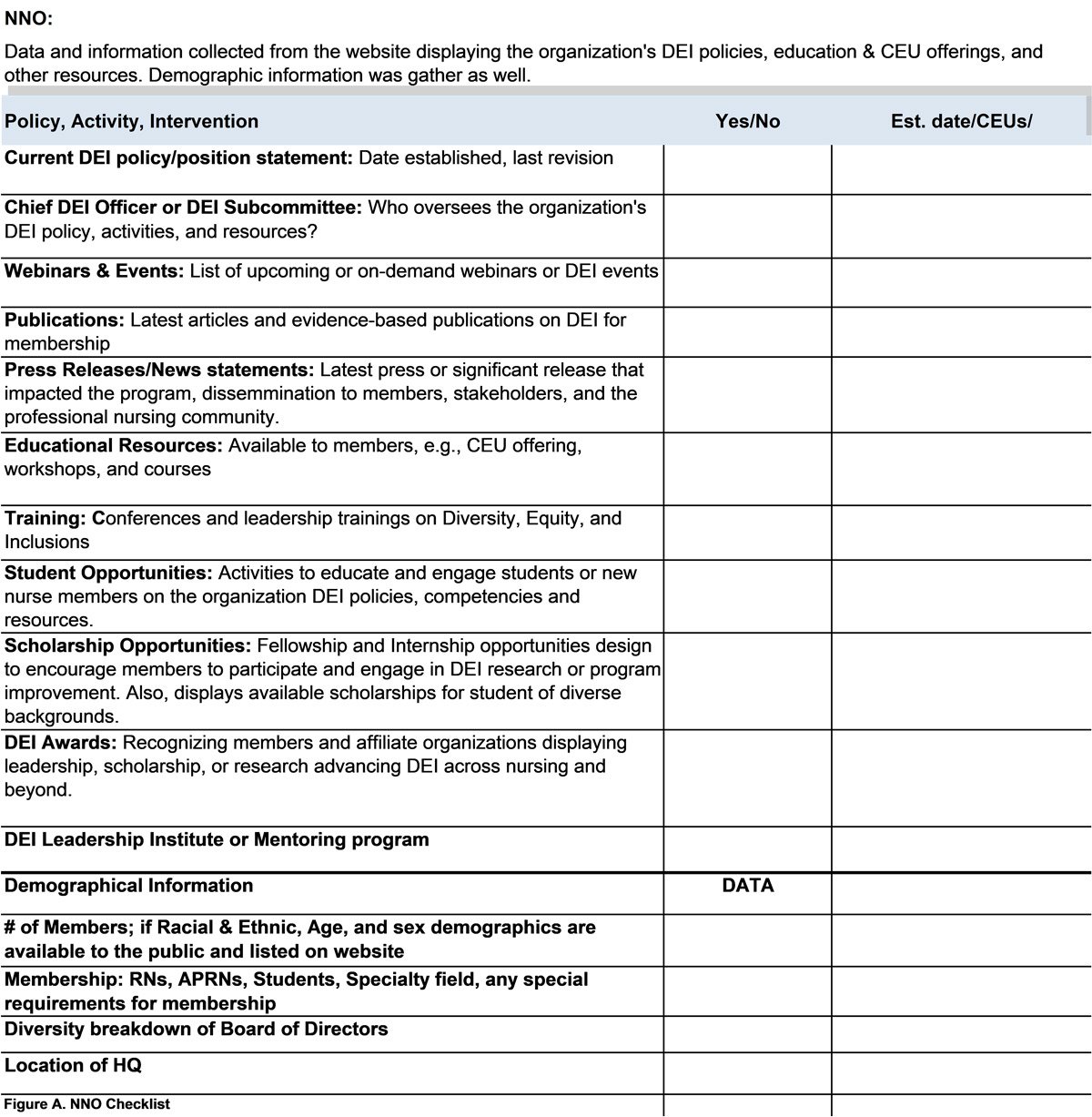

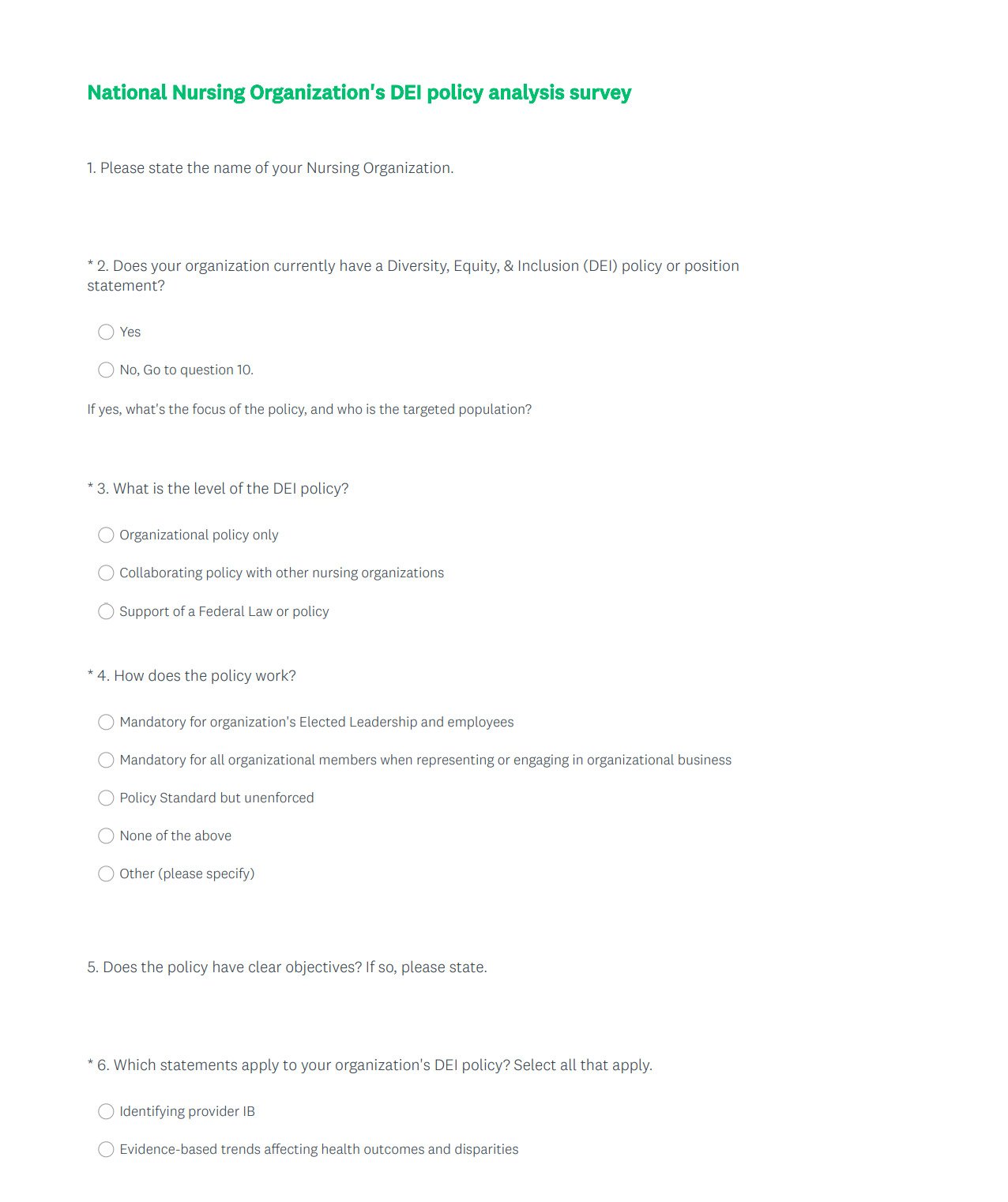

Data on NNO DEI policies was collected in two ways: 1) a manual search of NNO websites and their associated professional nursing journals and 2) a survey sent to NNO leaders. A list of 147 searchable NNOs was created from a comprehensive listing featured on Nursing.org (2022). An investigator-developed checklist was used to conduct NNO website analysis for searchable DEI policies. The ten-item investigator-developed DEI survey for NNO leaders allowed the NNO to clarify their DEI policy while verifying items collected on the website checklist. Both checklists followed the format of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) policy Analytical Framework questions to identify and describe policies (CDC, 2015).

Website Search

The following keywords were selected for the NNO policy analysis: “systemic racism,” “health disparities,” “diversity policy,” “DEI policies,” “diversity ," "equity training,” “DEI position statement,” “implicit bias,” and "national nursing organizations.” Pub Med, EBSCOhost electronic journal service, and CINAHL with full-text electronic databases were used to query research studies, white papers, policies, position statements, or journal reviews conducted, sponsored, or written by nursing organizations or nurses. Inclusion criteria included: a national professional nursing organization with 1) an active, published policy or official position statement addressing diversity, racism, or inclusion 2) DEI or a searchable policy or statement posted on the organization’s website. Data collected from each public NNO website was entered into a DEI Checklist (Figure A).

Figure A. NNO DEI Checklist

NNO Leader Survey

When selecting an NNO partnership for this analysis, it was critical to work with an organization that understands both IB in healthcare and policy implications. Partnering with an NNO committed to fostering and providing nurses within their membership access to DEI policies lends credibility to the essential response to IB by the nursing profession. The ANA is positioned to lobby nurses’ significant concerns on the national level while supporting state initiatives. In representing over four million nurses, ANA has a long reach and the ability to educate and influence nurses across the country. Many other NNOs look to ANA’s policy positions as a standard-bearer of the profession. As a formidable voice against systemic racism and the effects of IB in nursing, ANA demonstrates dedication through its DEI position statements and organizational policies (ANA, 2019). The organization fully supports DEI education and equips the nurse workforce for cultural responsiveness and self-awareness of IB. Collaborating with ANA to facilitate NNO outreach to conduct the organizational survey provided an added level of expertise, guided support, and acknowledgment of a timely topic as ANA leads efforts to address racism in nursing.

Each potential NNO received an electronic survey and consent via email from ANA (Figure B). If the NNO issued no active DEI policy, the survey asked about a future plan to create a DEI policy or position statement. The survey reinforced items from the website checklist while gathering other data to give context to the website analysis. Designation of non-human subjects research was obtained from a university Institutional Review Board prior to the analysis.

Figure B. NNO DEI Policy Analysis Survey

Results

Website Analysis

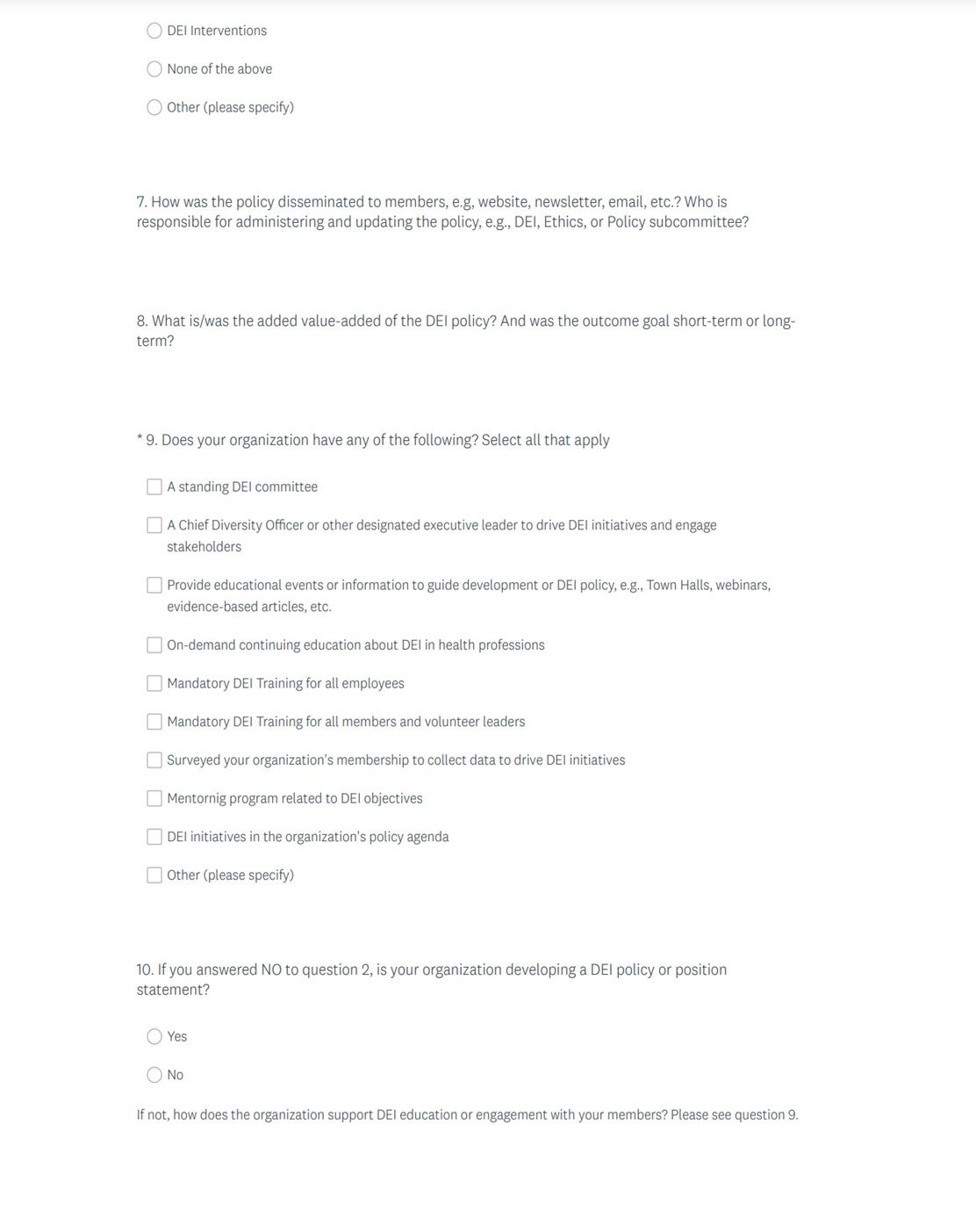

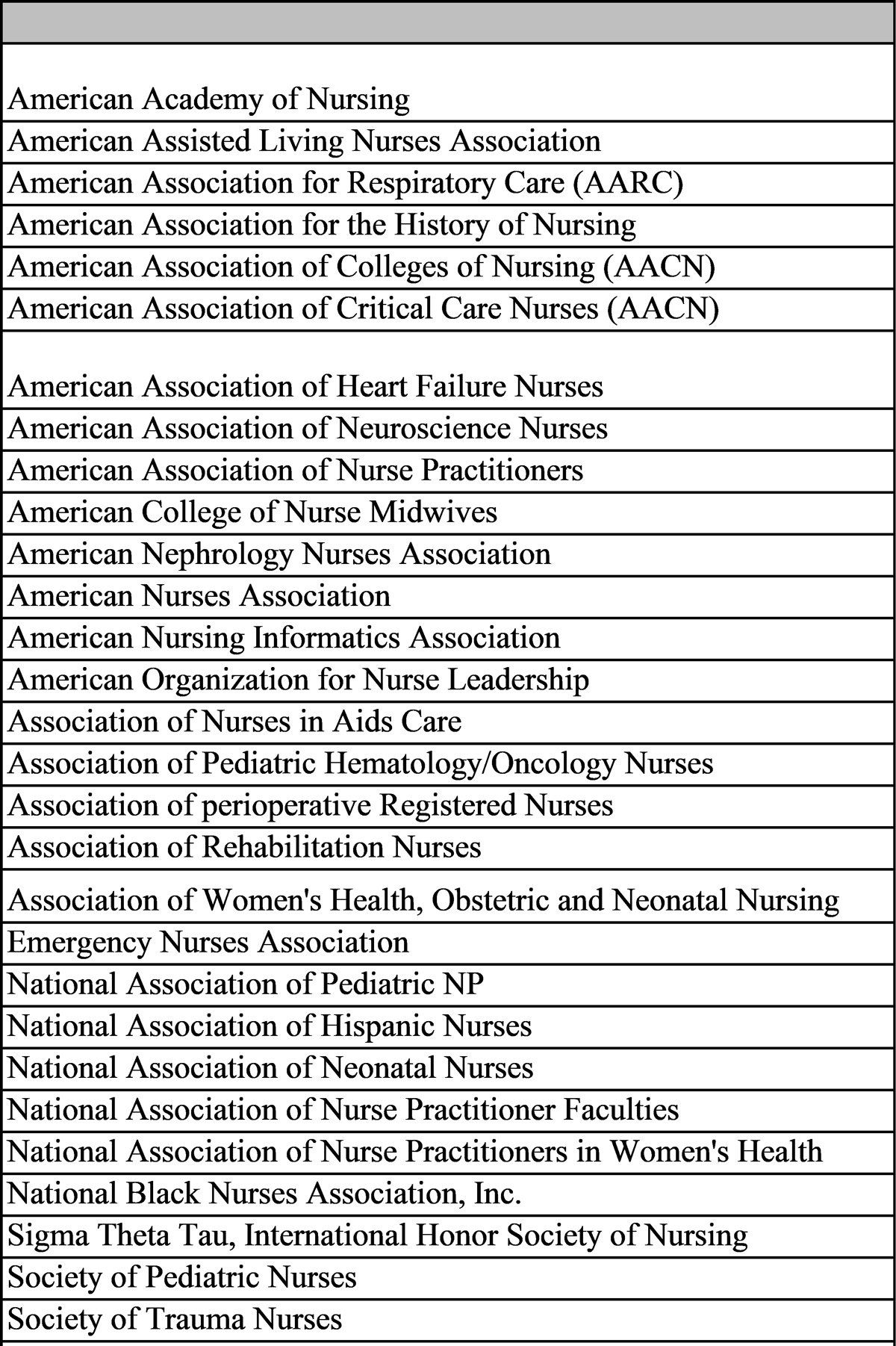

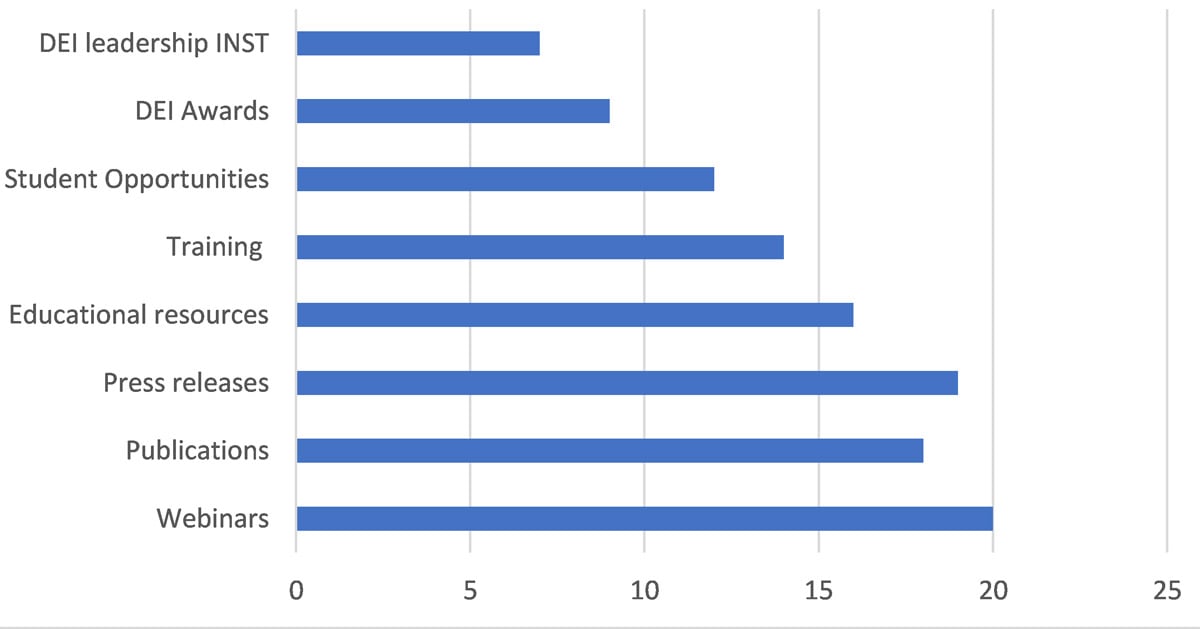

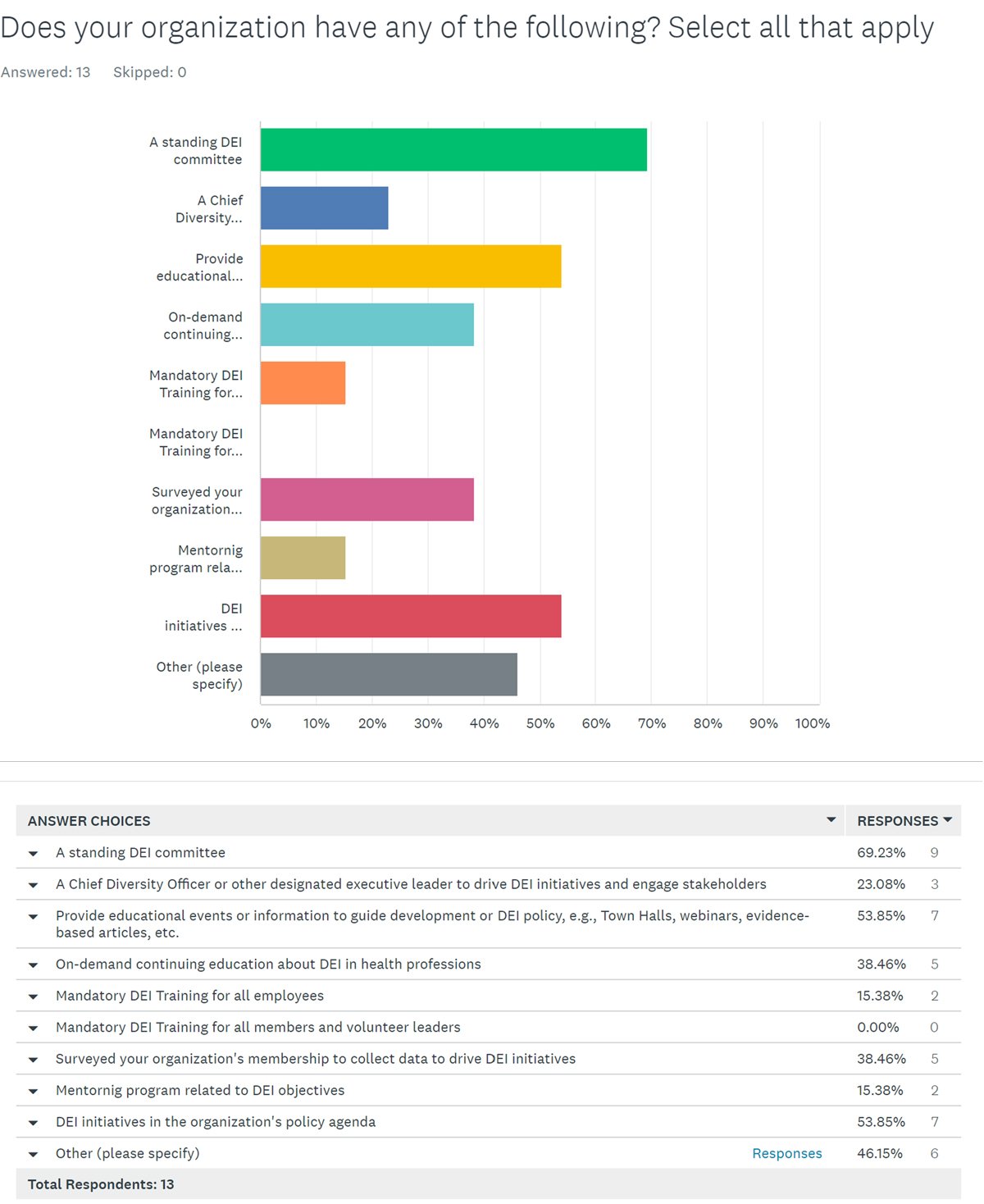

Of 147 identified NNOs through public website search, surveys were sent to107 NNO based on inclusion criteria. After further review, multidisciplinary organizations and Schools of Nursing were removed and added to the exclusion criteria to ensure the analysis focused only on NNOs. Therefore, eighty-eight (n=88) NNO websites (Table 1) were reviewed for DEI policies or position statements. Only 31% (n=29) of NNO websites (Table 2) revealed a DEI policy or statement. Of the fifty-eight NNOs without a DEI policy or statement on their website, four NNOs were identified to have either a commitment, Black Lives Matter (BLM), or racial equity statement, and one had a retired diversity policy. However, these were not included in the total because of the temporary nature of the statements and lack of an action plan to expand into an official policy or position statement. Only 10% of NNOs with DEI policies or statements explicitly addressed provider IB or DEI interventions. Seven NNOs had a dedicated DEI web page to provide resources and tools to their membership while highlighting the importance of diversity. Figure C displays the DEI resources and tools the NNOs disseminate to their members.

The Harvard Implicit Association Test (IAT) was the most referenced IB training test recommended to nurses The Harvard Implicit Association Test (IAT) was the most referenced IB training test recommended to nurses (Project Implicit, 2011). The Harvard IAT has a variety of tests individuals can use to gauge their potential bias covering different topics, e.g., race, weight, skin tone, and sexuality. The tool measures implicit attitudes an individual may be unaware of or unwilling to identify with and shows their initial instinctive responses (Project Implicit, 2011). The tests are available online and free to all.

Table 1. NNOs Website Analysis List

Table 2. NNOs with DEI Policies or Statements

NNO Survey Results

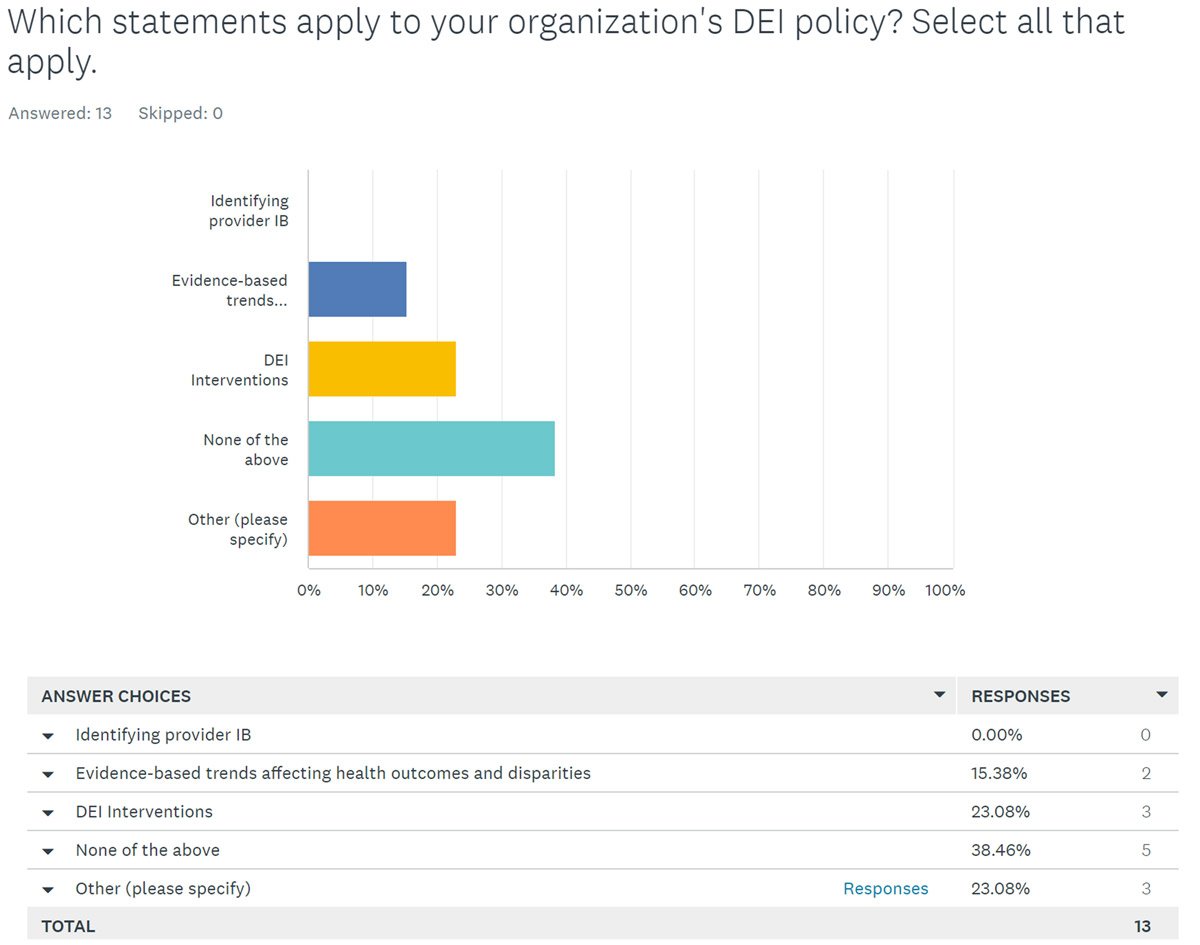

Thirteen responses were received from the electronic survey sent in collaboration with ANA. One duplicate response was excluded from the final sample. Eleven NNOs reported having a DEI policy or position statement. Two NNOs did not have a policy or position statement. NNOs without policies indicated they are in the process of developing a DEI policy or position statement but did not provide details about their action plan. NNOs whose policy focuses on provider IB, results affecting health outcomes and disparities, and DEI interventions are shown in Figure D. NNO reported DEI resources and tools are pictured in Figure E.

Figure C. NNO Website Dissemination of DEI Resource and Tools

Figure D. NNOs policies identifying provider Implicit Bias (IB)

Figure E. Survey DEI Resources and Tools

Discussion

Systemic racism and IB is considered a public health issue in the US. Nearly 20 years since the release of the first IOM study, only 31% of NNOs have a DEI policy or statement active on their website. Nurse-led research is needed to create more DEI resources and tools to educate and equip nurses to address this issue and its resultant healthcare impact. Furthermore, this review revealed that 34.5% of the NNOs’ policy or position statements are dated within the last 18 months, correlating with racially identified events that sparked several national movements.

While statements are an essential start in policy efforts, action is needed to create a well-defined program based on research and collaboration. NNOs with a newly published DEI or diversity policy or NNOs with only a statement should activate an operational implementation plan. It is insufficient to say the NNO has a DEI policy but has not implemented any resources, tools, or activities to educate, engage, or equip its members to follow through on stated values of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging.

A DEI policy platform aims to foster an environment in which nurses thrive because they believe their input is valued and accepted. In return, the goal is to encourage nurses to mirror the action of the NNO and develop a skillset to promote diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging within the nursing workforce and directed to the patients they serve. This report can assist NNOs without DEI programs to consider the data, policies, and clinical tools needed to create DEI policies to better serve their membership.

Limitations

The main limitation when conducting a web-based search is the potential to locate limited information and resources available to the public. There is a strong possibility that additional policy information was posted behind the NNO’s membership-only sections, which decreases the NNO’s influence and reach. Since the implementation phase of the review, some NNOs may have published a new or updated DEI policy or official statement. The removal of regional, state, and local nursing organizations and chapters limited the opportunities to assess if additional policies or statements exist and if they mirror the NNO’s statement or present a stand-alone position based on locational or internal influences.

Implications

This policy analysis provides the following recommendations for NNOs to best serve their nursing members in diversifying the profession and improving care outcomes for patients:

- Create a workgroup or commission to develop a DEI policy or position statement to demonstrate commitment to action.

- Recruit organizational leaders, including diverse volunteers from membership, who have experience and passion for invoking change and promoting equity and inclusion for all.

- Support adoption of DEI content in nursing education curricular standards and certification requirements.

- Consider policy statements and recommendations to facilitate diversification of the nursing workforce pipeline.

- Work collaboratively as NNOs to build consensus on universal nursing standards for DEI policies and position statements addressing racism, discrimination, or diversity across the nursing profession.

Conclusion

Issues of racial inequity and health disparities were highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic and brought to the forefront conversations of systemic racism in the United States. However, IB remains an unconscious influencer that has significant impact on the care of patients and health outcomes. NNOs are encouraged to leverage their leadership to educate their members to identify bias and offer tools to effectively promote change. NNOs have a meaningful opportunity to work together to advocate, strategize, and promote collaborative research to identify universal DEI standards to guide nursing practice.

Authors

Chandra Emanuel Jolley, DNP, BA, RN,

Commander (CDR), US Public Health Service (PHS) Commissioned Corps

Email: cjolley2@gmail.com

Dr. Jolley is a Senior Nurse officer in the United States Public Health Service, where she currently serves as a Senior Public Health Analyst stationed in Rockville, MD. CDR Jolley’s expansive career spans over the 25 years displaying her distinctively unique and diverse experience in law, finance, and nursing. CDR Jolley has demonstrated her passion for nursing and leadership through her service to the Corps and the nursing profession. She has facilitated lectures, presented at various national nursing conferences, participated in research projects, mentored multiple officers and civilians, and contributed to various workgroups. She obtained a Bachelor of Art from Morris Brown College in Pre-Law, received her Bachelor of Science in Nursing from Clayton State University, and a Master of Science in Nursing from George Washington University in Leadership and Management. She recently graduated from Baylor University with a Doctor in Nurse Practice in Midwifery.

Jessica L. Peck, DNP, APRN, CPNP-PC, CNE, CNL, FAANP, FAAN

Email: Jessica_Peck@Baylor.edu

Dr. Jessica Peck is an expert pediatric nurse practitioner and anti-trafficking nurse advocate who provides innovative, visionary, and award-winning leadership to develop and lead inclusive and diverse interprofessional teams to provide outcomes of high-quality health care. She served as founding Chair of the Alliance for Children in Trafficking, a national advocacy campaign of the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners Partners for Vulnerable Youth, where she works with other national organizations to equip healthcare professionals to combat human trafficking of children and advocates for other vulnerable youth populations. Dr. Peck worked with the US Department of Health and Human Services as part of an interprofessional team to create a set of core competencies for health care professionals caring for trafficked individuals, published in 2021. She serves as the Lead Medical Consultant for Unbound Houston and effectively advocated to create a statewide continuing education program and pass legislation mandating continuing education for all care providers in Texas. Dr. Peck is currently a Clinical Professor of Nursing at Baylor University in Dallas, Texas. She holds active credentials as a Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, a Certified Nurse Educator, and a Clinical Nurse Leader. Dr. Peck has been practicing as a Pediatric Nurse Practitioner for more nearly 20 years in primary care environments.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2013, June). 2012 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Quality and Disparity Reports. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/index.html

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2006). The essentials of doctoral education for advanced nursing practice. https://www.aacnnursing.org/DNP/DNP-Essentials

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2008). The essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/BaccEssentials08.pdf

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2011). The essentials of master’s education in nursing. https://www.aacnnursing.org/portals/42/publications/mastersessentials11.pdf

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2017) Diversity, equity, and inclusion, in academic nursing [Position statement]. Publications on Diversity. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Diversity-Equity-and-Inclusion/Publications-on-Diversity/Position-Statement

American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM). (n.d.). Diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging. Engage. https://midwife.org/deib

ANA Ethics Advisory Board. (2019, June 7). ANA position statement: The nurse’s role in addressing discrimination: Protecting and promoting inclusive strategies in practice settings, policy, and advocacy. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 24(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No03PoSCol01

Bardach, E. S., & Patashnik, E. M. (2020). A practical guide for policy analysis: The eightfold path to more effective problem solving (6th.). SAGE.

Blair, I. V., Havranek, E. P., Price, D. W., Hanratty, R., Fairclough, D. L., Farley, T., Hirsh, H. K., & Steiner, J. F. (2013). Assessment of biases against latinos and african americans among primary care providers and community members. American Journal of Public Health, 103(1), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2012.300812

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2015). CDC’s policy analytical framework. Health Policy Analysis and Evidence. https://www.cdc.gov/policy/analysis/process/analysis.html

Chatterjee, A., Greif, C., Witzburg, R., Henault, L., Goodell, K., & Paasche-Orlow, M. K. (2020). US Medical School Applicant Experiences of Bias on the Interview Trail. Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved, 31(1), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2020.0017

Chiu, P., Duncan, S., & Whyte, S. (2020). Charting a research agenda for the advancement of nursing organizations’ influence on health systems and policy. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 52(3), 185-193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0844562120928794

Dehon, E., Weiss, N., Jones, J., Faulconer, W., Hinton, E., Sterling, S. (2017). A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making. Academic Emergency Medicine, 24(8), 895–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13214

Effland, K. J., & Hays, K. (2018). A web-based resource for promoting equity in midwifery education and training: Towards meaningful diversity and inclusion. Midwifery, 61, 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.02.008

Gatewood, E., Broholm, C., Herman, J., & Yingling, C. (2019). Making the invisible visible: Implementing an implicit bias activity in nursing education. Journal of Professional Nursing, 35(6), 447–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.03.004

Hagiwara, N., Elston Lafata, J., Mezuk, B., Vrana, S. R., & Fetters, M. D. (2019). Detecting implicit racial bias in provider communication behaviors to reduce disparities in healthcare: Challenges, solutions, and future directions for provider communication training. Patient Education & Counseling, 102(9), 1738–1743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.04.023

Hall, W. J., Chapman, M. V., Lee, K. M., Merino, Y. M., Thomas, T. W., Payne, B. K., Eng, E., Day, S. H., & Coyne-Beasley, T. (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e60–e76. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903

Institute of Medicine [IOM] Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Smedley, B. D., Stith, A. Y., & Nelson, A. R. (Eds.). (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12875

Maina, I. W., Belton, T. D., Ginzberg, S., Singh, A., & Johnson, T. J. (2018). A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009

Maxfield, C. M., Thorpe, M. P., Desser, T. S., Heitkamp, D., Hull, N. C., Johnson, K. S., Koontz, N. A., Mlady, G. W., Welch, T. J., & Grimm, L. J. (2020). Awareness of implicit bias mitigates discrimination in radiology resident selection. Medical Education, 54(7), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14146

Nursing.org. (2022). List of nursing organizations. Resources. https://nurse.org/orgs.shtml

Oliver, M. N., Wells, K. M., Joy-Gaba, J. A., Hawkins, C. B., & Nosek, B. A. (2014). Do physicians’ implicit views of african americans affect clinical decision making? Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 27(2), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.120314

O’Rourke, N. C., Crawford, S. L. Morris, N. S., & Pulcini, J. (2017). Political efficacy and participation of nurse practitioners. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 18(3), 135-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154417728514

Peck, J. L. (2022). Partners for vulnerable youth and the alliance for children in trafficking: Using the policy circle model as a framework for change. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 36(2), 144-153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2020.10.001

Project Implicit. (2011). Harvard Implicit Test. Overview. https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/education.html

van Ryn, M., Hardeman, R., Phelan, S. M., Burgess, D. J., Dovidio, J. F., Herrin, J., Burke, S. E., Nelson, D. B., Perry, S., Yeazel, M., & Przedworski, J. M. (2015). Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: A medical student CHANGES study report. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(12), 1748–1756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3447-7