Hospital nurses often experience challenges when teaching older adults about fall prevention strategies. The goal of this project was to provide evidence-based training to hospital nurses to facilitate patient engagement with fall prevention measures. Methods: An “Adapted” Motivational Interviewing (MI) for fall prevention (AMIFP) training in acute care was developed and introduced to nurses as part of a Veterans Affairs-Nursing Academic Partnership (VANAP) initiative. Pre/post surveys were completed by 61 nurses (71% response rate) at an acute care hospital in the United States. Results: After the single AMIFP training, nurses reported having increased knowledge about patient engagement related to fall prevention. Moreover, feelings of confidence related to using some MI skills for fall prevention increased after training. Conclusion: Even a brief AMIFP training for nurses can have a positive impact on improving hospital nurses’ knowledge and attitudes to engage patients in fall prevention education.

Key Words: Fall prevention, patient engagement, fall risk, patient education, motivational interviewing, nursing care of the elderly

More than 700,000 people fall in the hospital every year in the United States...and a third of these falls are reported as preventableFall prevention is an important patient safety topic in hospital settings. Many hospitals have inpatient fall prevention programs with varied impact of these programs in reducing fall rates (Cameron et al., 2012; Tzeng & Yin, 2015). More than 700,000 people fall in the hospital every year in the United States (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2013) and a third of these falls are reported as preventable (Cameron et al., 2012). An innovative approach to address inpatient fall prevention is critically needed to improve patient safety outcomes.

In a preliminary study examining the gap between the structure and implementation of a fall prevention program and patients’ experience, we found that only 26% of patients disclosed high fall risk despite a clinical assessment indicating high risk for falls (Kiyoshi & Rose, 2017). Only 33% of participants remembered receiving any fall prevention education despite receiving fall risk education at least daily (Kiyoshi & Rose, 2017). Based on these findings, this manuscript describes a follow-up project to improve nurses’ engagement with patients about fall prevention. The specific aim was to explore how introduction to an “adapted” version of Motivational Interviewing (MI), an evidence-based patient engagement approach, may shift nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward engaging patients in fall prevention education.

Background

Patient education is an integral part of hospital fall prevention programs (AHRQ, 2013). However, fall prevention education can be challenging for patients and nurses. For example, older adults are often not interested in receiving fall prevention education as many perceive fall prevention recommendations as not personally relevant (McMahon, Talley, & Wyman, 2011). Some older adults object categorization as high fall risk possibly due to fears of being viewed as dependent or incompetent (Gardiner et al., 2017). In addition, in hospital settings, patients often take risks that may lead to falls, such as unassisted movement from beds or restrooms (Haines, Lee, O'Connell, McDermott, & Hoffmann, 2015). Nurses’ often perceive fall prevention education as unimpactful to patient risk behaviors (King, Pecanac, Krupp, Liebzeit, & Mahoney, 2018) or have negative feelings on the topic (Bok, Pierce, Gies, & Steiner, 2016). Considerations of patient and nurses’ biases must be addressed for fall prevention education to be beneficial in the hospital setting.

...older adults are often not interested in receiving fall prevention education as many perceive fall prevention recommendations as not personally relevant Patient engagement essential to improve patient safety (AHRQ PSNet, 2018). MI is a well-established communication approach to engage clients in health behavior change (Copeland, McNamara, Kelson, & Simpson, 2015; Lundahl et al., 2013; Söderlund, Madson, Rubak, & Nilsen, 2011). MI is especially suitable when ambivalence about the health behavior exists (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). Emotional conflicts and indecision about fall prevention are well documented (McMahon et al., 2011). In MI, positive messaging, and techniques such as Open-ended questions, Affirmation, Reflection, and Summary statements (OARS) are used to facilitate patient engagement (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). Because MI emphasizes collaboration with patients rather than increasing fear or instructing patients, MI-based fall prevention has a potential to positively shift nurses’ communication approach with their patients about fall prevention.

Initial efforts to apply MI to fall prevention have been supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). The CDC specifically recommends clinicians to tailor fall prevention messages to patients by determining an older adult’s Stage of Change (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997) and to use MI to facilitate behavior change in this population. Furthermore, research studies on physical activity for fall prevention in the community utilize MI as an intervention (McMahon et al., 2011; Arkkukangas & Hultgren, 2019). However, MI has not been directly applied to fall prevention efforts in hospital settings.

Therefore, questions guiding this exploration include: (a) How can MI be incorporated into fall prevention efforts in hospital settings? (b) What is the acceptability of this approach by nurses? (c) What is the feasibility of this approach in an acute care setting?

The VA-Nursing Academic Partnership (VANAP) initiative provided an excellent opportunity to explore these questions. The goal of this partnership was to create an innovative education and practice collaboration (U. S. Department of Veteran Affairs, 2018). Thus, authors and clinicians collaborated to create a brief nursing training targeted to introduce “adapted” MI as an evidence-based patient-engagement approach for fall prevention. Changes in nurses’ knowledge and attitudes about patient engagement related to fall prevention were evaluated. The goal of this project was to use Motivational Interviewing to shift nurses' knowledge and perceptions about fall prevention education.

Methods

Design and study procedures

This project utilized quasi-experimental, single arm, pre-post design to evaluate the impact of brief introduction of “adapted” MI for fall prevention.This project utilized quasi-experimental, single arm, pre-post design to evaluate the impact of brief introduction of “adapted” MI for fall prevention. Nurses completed the pre-survey right before the training, and the post-survey immediately after the training. Surveys were paper-based and responses to the surveys were kept anonymous. Participants were asked to create and write a four-digit code (e.g., last four digits of a phone number) so that their responses could be matched between pre- and post- survey responses. This project was submitted to Oregon Health & Science University/Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System Institutional Review Boards as a quality improvement project, and approval was obtained prior to the data collection.

Participants and setting

Full-time and part-time acute care registered nurses (RNs), patient-care assistants (PCAs), and nursing students at Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System were eligible to participate in this study. Certified patient care assistants were included as they are an integral part of fall prevention by assisting patients with daily activities and ambulation under registered nurses’ supervision. Nursing students were also included as they are involved in transferring patients and providing patient education on fall prevention. Charge nurses and managers covered nurses’ workload as needed so bedside nurses could participate in the training. Participants did not receive any incentives to participate in the project.

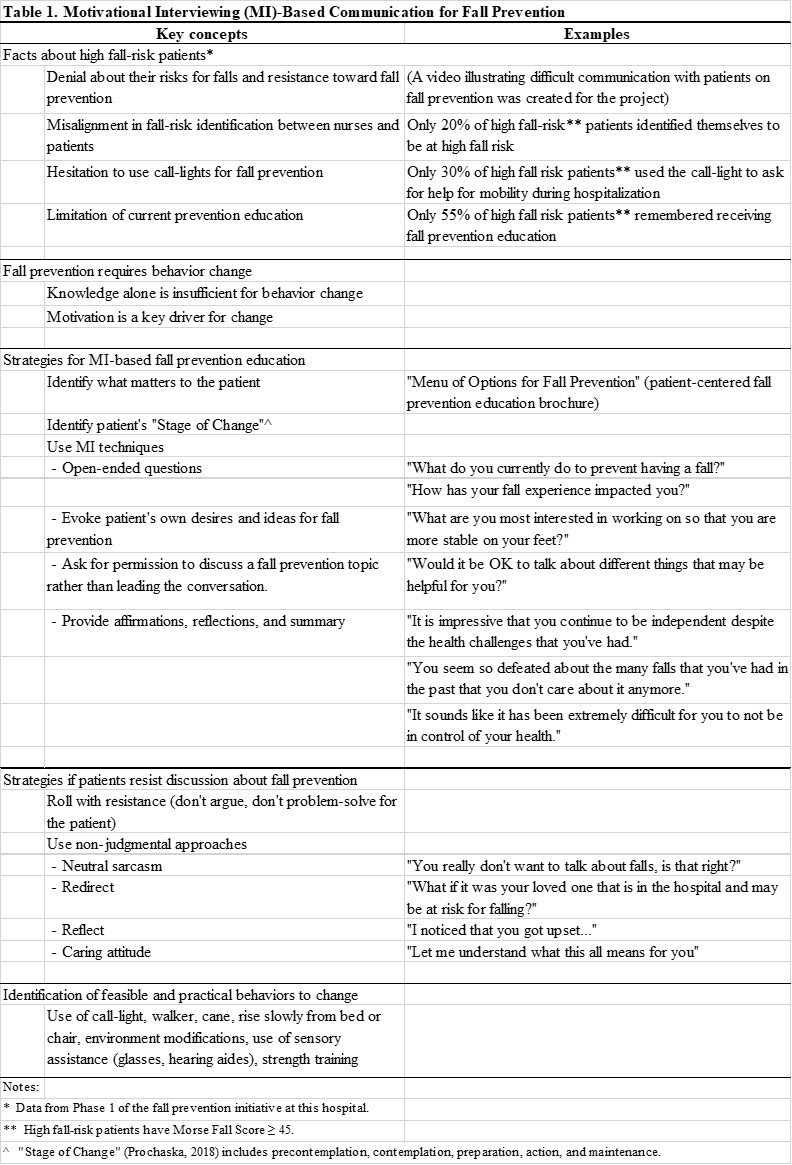

“Adapted” MI for fall prevention (AMIFP) training

A 30-minute training session was created and delivered for this study for nurses to attend once. See Table 1 for the description of the content. This 30-minute MI training was minimal compared to traditional introductory 8-24 hour MI training. Since our goal was to gain preliminary insight into how MI can be introduced into acute care practices, we delivered in this format based on consultation from clinical partners. To increase participation, training sessions were offered during routine shifts on the hospital floor at 5am and 11am on multiple days of the week so that participants could attend at a convenient time during work hours. The primary author consulted with an MI trainer who has doctorate in nursing, a psychologist who is a clinician MI trainer at this hospital, and a Clinical Nurse Specialist who led hospital-wide fall prevention initiatives throughout the project to create and evaluate the training sessions.

During the session, nurses were briefly introduced to limitations of current fall prevention practices at the hospital using data from the preliminary study. Participants were informed that high fall risk patients do not necessary consider themselves as high risk for falling or remember receiving fall education, and have hesitancy to use call-light for mobility (Kiyoshi, Carter, & Rose, 2017). A 5-minute video that illustrated how a patient can demonstrate resistance toward fall prevention was presented.

Table 1.

The AMIFP training introduced elements of OARS but emphasized “OEP” (Open-ended questions, Evoking patient’s own desire and ideas for fall prevention, and asking for Permission to discuss a fall prevention topic)The AMIFP training introduced elements of OARS but emphasized “OEP” (Open-ended questions, Evoking patient’s own desire and ideas for fall prevention, and asking for Permission to discuss a fall prevention topic) (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). These approaches align with current fall prevention practice, are action-oriented, simple, and distinctively different from a typical conversation about fall prevention. For example, a typical fall prevention conversation will start with close-ended question of “have you had a fall in the past 3 months?” In the training, we suggested that a nurse follow-up with an open-ended question “how has the fall impacted you?” Then ask an evoking question: “What would be helpful to talk about for you to be safe while you are in the hospital?” And, finally, asking for permission, “Is it OK to talk about that?” This contrasts to a typical approach in where if the patient has had a fall, the nurse proceeds to educate without asking about patient’s interest in the topic (i.e., not exploring personal circumstances or their own ideas about fall prevention) or about their fall risks and safety measures (i.e., use the call light, use the walker).

Measures

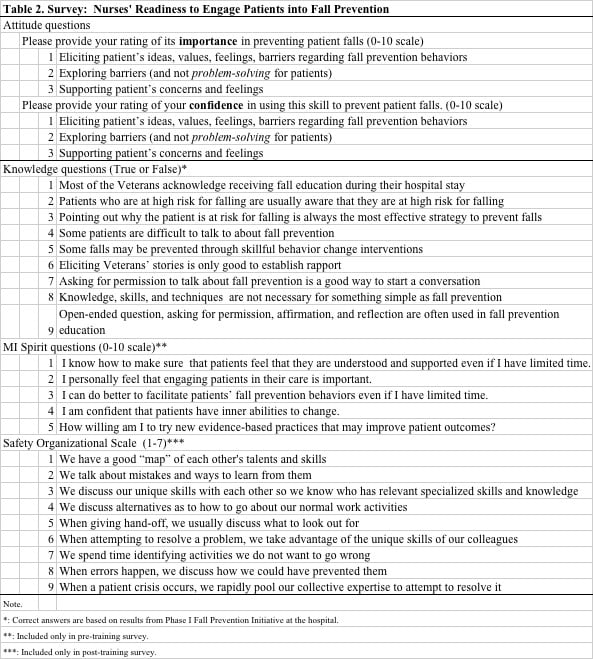

Authors created the Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitudes to Engage Patients in Fall Prevention Survey based on literature, prior findings, and existing instruments (Table 2). Knowledge and attitude questions (15 questions) were asked in both pre- and post-surveys. Additional items captured baseline “MI spirit” (5 questions; pre-survey) and culture of safety of the floor (post-survey; 9 questions).

Table 2.

Attitudes toward patient engagement for fall prevention were assessed by the reported levels of importance and confidence on three statements related to patient engagement: (a) eliciting patient’s ideas and values; (b) exploring barriers; and (c) supporting patient’s concerns and feelings. These patient engagement statements were based on VA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention internal publication (2011) and were used to evaluate the impact of clinician MI training. The levels of importance or confidence were rated on a ten-point rulers/ scale (0= Not important/confident, 10=Extremely important/confident). These rulers are widely used in clinical settings in behavior change interventions (Bertholet, Gaume, Faouzi, Gmel, & Daeppen, 2012).

Attitudes toward patient engagement for fall prevention were assessed by the reported levels of importance and confidence on three statements related to patient engagement: (a) eliciting patient’s ideas and values; (b) exploring barriers; and (c) supporting patient’s concerns and feelings. Knowledge questions about the reality of patient engagement related to fall prevention were created by the authors based on findings from the first phase of the fall prevention initiative (Kiyoshi, Carter, & Rose, 2017). Respondents were asked to indicate true or false to nine knowledge statements such as, “Most of the Veterans acknowledge receiving fall education during their hospital stay.”

The “MI spirit” questions were included in the pre-survey to capture participants’ personal beliefs in the client’s internal ability to change and personal willingness to try MI. (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). Authors created “MI spirit” questions through theoretical understanding of this concept (Miller & Rollnick, 2012).

The post-survey included the Safety Organizing Scale (SOS) (Vogus & Sutcliffe, 2007) to capture the safety culture of the two hospital units included in this project. We expected each hospital unit to have a unique safety culture that may systematically impact individual nurses’ beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes. SOS is well-published unidimensional measure of behaviors theorized to underlie a safety culture with a reported Cronbach alpha of 0.88 (Vogus & Sutcliffe, 2007). Specifically, for fall prevention, SOS score was negatively correlated to frequency of patient falls (B= -0.629, p<.001) (Vogus & Sutcliffe, 2007) meaning stronger safety cultures were correlated with fewer falls. Permission was granted to use the SOS tool.

Analysis

Means and frequencies were calculated for descriptive analyses. Paired t-tests were used to compare differences among groups (e.g., hospital units, clinical roles, and day-night shifts) and pre- and post- survey scores when appropriate. Statistical significance was tested using two-tailed tests with an alpha set at 0.05.

Results

Demographics

Thirteen training sessions were conducted through September-November 2015. A total of 85 nurses participated in the training. The final sample (N=61) included those who completed both surveys (71% response rate). Participants included 40 RNs, 10 CNAs, and six nursing students. Five respondents did not report their roles on the unit. The sample represented both day and night shift nurses (Day: 36 and Night: 22), and two medical-surgical units (Unit A: 20, Unit B: 41). Three respondents did not report the shift that they primarily work.

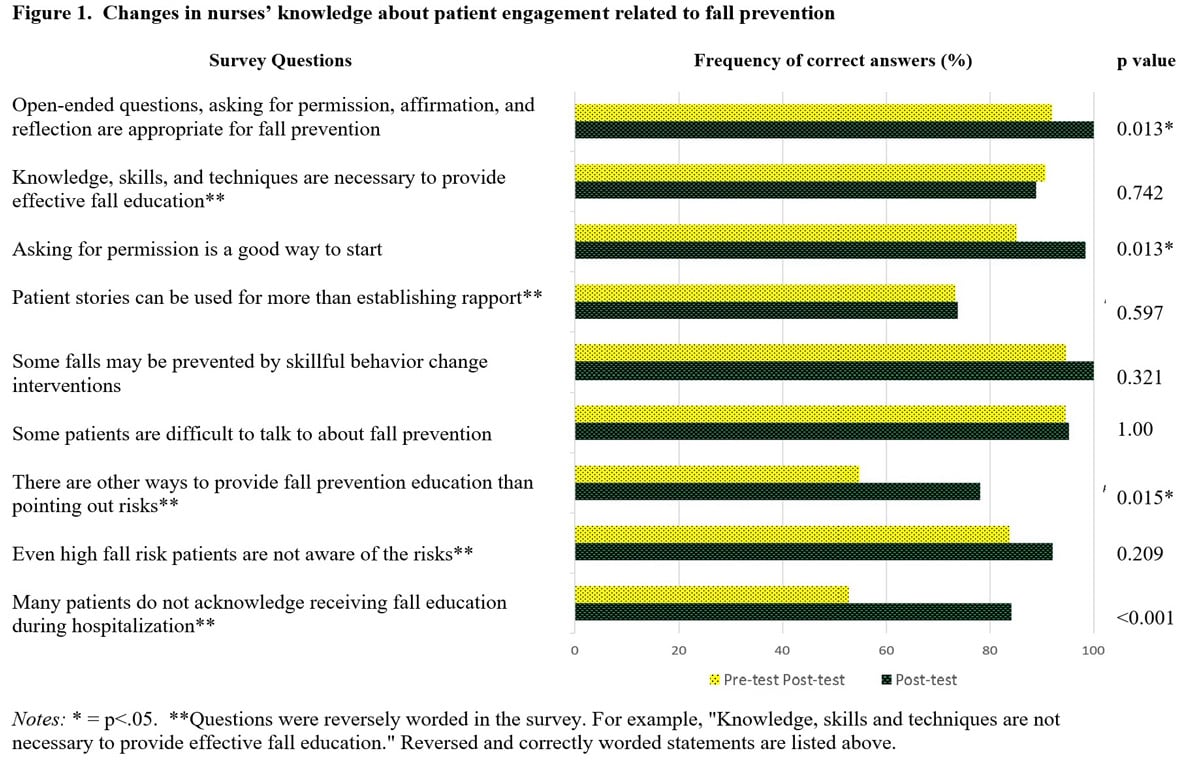

Changes in knowledge about patient engagement related to fall prevention

The frequency of participants answering correctly to the knowledge questions increased from an average of 80% to 90% after the training across the nine questions (Figure 1). Specifically, after the training, more participants were aware that: (a) there are other ways to provide fall prevention education than pointing out their risks for falling (Pre: 54.7%, Post: 78.1%, p=.015); (b) many patients do not remember or acknowledge receiving fall education during hospitalization (Pre: 52.7%, Post: 84.1%, p<.001); (c) asking for permission to talk about fall prevention is a good way to start a conversation (Pre: 85.1 %, Post 98.4%, p<.013); and (d) open-ended questions, affirmation, reflection and asking for permission, are appropriate for fall prevention (92% vs. 100%, p<.013).

Figure 1.

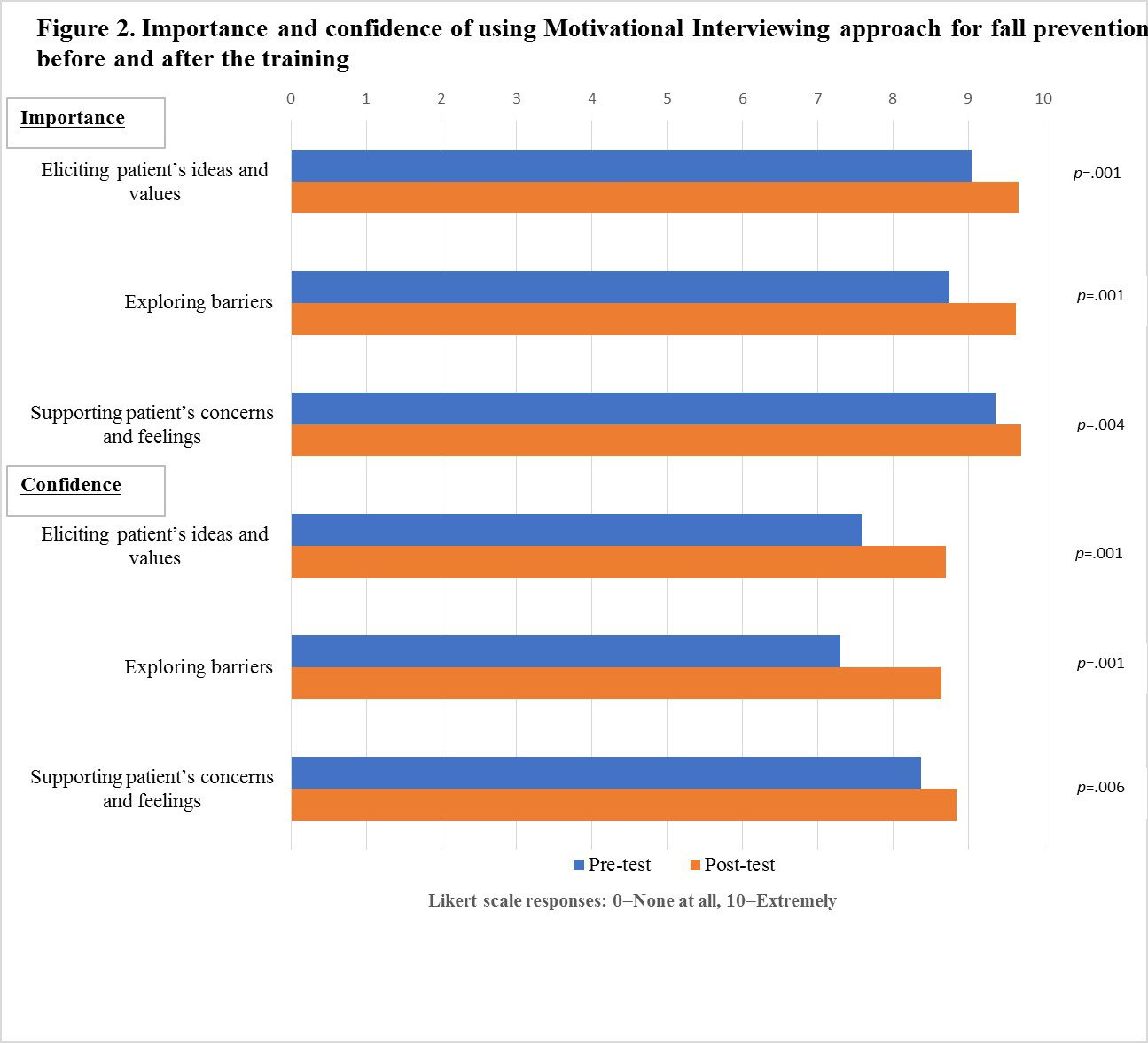

Changes in nurses’ attitudes about patient engagement in fall prevention

The nurses’ reported level of importance to use the following approaches improved consistently and statistically significantly: (a) eliciting patient’s ideas and values (Pre: 9.05, Post: 9.67, p<.001), (b) exploring barriers (Pre: 8.75, Post: 9.64, p<.001), and (c) supporting patient’s concerns and feelings (Pre: 9.36, Post: 9.70, p=.004) (Figure 2). Nurses’ level of confidence to use the following approaches to engage patients in fall prevention improved after the training but were still lower compared to the level of importance: (a) eliciting patient’s ideas and values (Pre: 7.59, Post: 8.70, p<.001), (b) exploring barriers (Pre: 7.30, Post: 8.64, p<.001), and (c) supporting patient’s concerns and feelings (Pre: 8.38, Post: 8.84, p=.006).

Figure 2.

MI spirit

“MI spirit” item scores were high (7.9-9.4; 0-10 possible scores) with an average of 8.6. The Cronbach's alpha, a reliability coefficient that indicates how much scaled items measure the same underlying dimension was 0.61, not meeting the acceptability level of 0.70 (Polit, 1996) however, indicated sufficient evidence of reliability for this small-scale project. There is a need for further improvement or a larger sample size for this scale in future research. Thus, for the results, we reported on item responses rather than aggregate scores. Questions from MI spirit did not result in any systemic differences between units about MI spirit questions (Unit A: 7.9-9.4, Unit B: 7.8-9.7, p= .106- .892). There were some differences between nursing roles; Q 17. “I personally feel that engaging patients in their care is important” (RN: 9.5, CNA: 9.9; p=.015), Q 18. “I can do better to facilitate patients’ fall prevention behaviors even if I have limited time” (RN: 8.5, CNA: 7.3; p=.048). Between day and night shift nurses, there was a difference on the question “How willing I am to try evidence-based practices that may improve patient outcomes?” (Day: 9.6, Night: 9.1, p=.030).

Safety Organizing Scale

SOS item score for our sample was slightly high at 5.3 (1-7 possible score). This score was similar to previously published mean scores of 4.76 to 5.86 (n=1,685) (Vogus & Sutcliffe, 2007), indicating a moderate level of a culture of safety to facilitate fall prevention practices of nurses. The Cronbach alpha was 0.91, thus, supporting internal consistency of SOS scale (Polit, 1996). Questions from SOS did not result in any systemic differences between units (Unit A: 5.2, Unit B: 5.3, p=.236), between nursing roles (RN: 5.5, PCA: 5.1; p=.740), or between day and night shifts (Day: 5.3, Night: 5.3, p=.681). The MI Spirit and SOS questions were only assessed one time, as they measure belief and culture which are unlikely to change in a day.

Limitations

Limitations include data collection at a single hospital with a small sample size, however, we were still able to compare the difference in belief and safety culture between clinical roles and day- and night- shift nurses. The self-report nature of the survey has a potential bias for social desirability to over-report any changes during the training. The post-training survey only measured immediate changes and not knowledge retention or attitude change over time. MI Spirit questions did not yield an acceptable reliability score and requires further improvement for future studies. The AMIFP training included brief introductory content and was not intended to train the MI trainer. Because AMIPH trainings were offered during clinical shifts, some nurses were not able to attend a full 30-minute session.

Discussion

We introduced an evidence-based communication approach, MI, in a practice-oriented way to bedside nurses. The AMIFP training was effective in improving hospital nurses’ knowledge and attitudes related to patient engagement. Application of MI for fall prevention has been limited (McMahon et al., 2011; Schepens, Panzer, & Goldberg, 2011), however, this project found that nurses valued principles embedded in MI, and even a single training is effective in introducing new and engaging ways that nurses can communicate about fall prevention. The AMIFP provides a practice-aligned introduction of MI to incorporate recommendations of the CDC (2017) to tailor the fall prevention education message according to each patient’s readiness to change.

The AMIFP training was effective in improving hospital nurses’ knowledge and attitudes related to patient engagement. Based on the improvement in nurses’ pre- and post-survey results on eliciting patient’s ideas and values and exploring barriers after the AMIFP training, we suggest that future fall prevention training for nurses should incorporate how nurses can include open-ended questions when addressing fall risks with patients. An open-ended question such as “how did this fall impact you?” can be added to the standard hospital admission question about patients’ recent fall experiences. Fall prevention training for nurses can highlight how open-ended questions can illustrate the nurse’s non-judgmental caring curiosity and willingness to hear the patient’s view. This question can be a starting point for nurses to learn more about patient’s perceptions about their fall risks and knowledge about fall prevention and identify creative ways to engage patients in fall prevention strategies.

Conclusion

The training on AMIFP, although brief, improved nurses’ knowledge and attitudes related to fall prevention and patient engagement. Using this approach, nurses can gain insight into patients’ readiness to engage with fall prevention as they co-create fall prevention strategies. Patient communication approaches identified through this project can strengthen the existing fall prevention education provided by nurses.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible through the United States Department of Veteran Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and the leadership and clinical staff at Oregon Veterans Affairs Nursing Academic Partnerships (VANAP) Veteran Learning Communities (VLC).

Funding

Faculty position for Hiroko Kiyoshi-Teo was funded by Oregon VANAP program at the time of the data collection.

Disclaimer

The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Authors

Hiro Kiyoshi-Teo, PhD, RN

Email: kiyoshi@ohsu.edu

Dr. Kiyoshi-Teo is an Assistant Professor in the School of Nursing at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland, Oregon. Dr. Kiyoshi-Teo's program of research is to explore strategies to overcome barriers and promote facilitators of patient-centered, evidence-based nursing interventions. Her work spans from prevention of device-related infections (ventilators, urinary catheters, and peripherally inserted central catheters) to fall prevention. Her current work focuses facilitating behavior change for fall prevention with older adults using Motivational Interviewing.

Kathlynn Northrup-Snyder, PhD, RN, PHN

Email: kns_cns@msn.com

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8832-6675

Dr. Northrup-Snyder’s expertise and research target public health nursing, health promotion, behavior change theory, and Motivational Interviewing (MI). She has been a member of Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) since 2008 and presented on research and use of distance technology for teaching MI, exemplifying expertise in MI training methods. She is trained in the use of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity coding tool and the Helpful Responses Questionnaire.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2013, January). Preventing falls in hospitals: A toolkit for improving quality of care. AHRQ. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications2/files/fallpxtoolkit-update.pdf

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, PSNet. (2018, January 1). Update: Patient engagement in safety. Perspectives. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/perspective/update-patient-engagement-safety#Annual-Perspective-2018

Arkkukangas, M., & Hultgren, S. (2019). Implementation of motivational interviewing in a fall prevention exercise program: Experiences from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Research Notes, 12(1), 270. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4309-x

Bertholet, N., Gaume, J., Faouzi, M., Gmel, G., & Daeppen, J.-B. (2012). Predictive value of readiness, importance, and confidence in ability to change drinking and smoking. BMC Public Health, 12, 708. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-708

Bok, A., Pierce, L. L., Gies, C., & Steiner, V. (2016). Meanings of falls and prevention of falls according to rehabilitation nurses: A qualitative descriptive study. Rehabilitation Nursing, 41(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/rnj.221

Cameron, I. D., Gillespie, L. D., Robertson, M. C., Murray, G. R., Hill, K. D., Cumming, R. G., & Kerse, N. (2012). Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals | Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, 12, CD005465. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub3

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017). Fact sheet: Talking about fall prevention with your patients. STEADI Initiative for Health Care Provider. https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/Talking_about_Fall_Prevention_with_Your_Patients-print.pdf

Copeland, L., McNamara, R., Kelson, M., & Simpson, S. (2015). Mechanisms of change within motivational interviewing in relation to health behaviors outcomes: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(4), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.022

Gardiner, S., Glogowska, M., Stoddart, C., Pendlebury, S., Lasserson, D., & Jackson, D. (2017). Older people’s experiences of falling and perceived risk of falls in the community: A narrative synthesis of qualitative research. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 12(4), e12151. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12151

Haines, T. P., Lee, D.-C. A., O’Connell, B., McDermott, F., & Hoffmann, T. (2015). Why do hospitalized older adults take risks that may lead to falls? Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 18(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fhex.12026

King, B., Pecanac, K., Krupp, A., Liebzeit, D., & Mahoney, J. (2018). Impact of fall prevention on nurses and care of fall risk patients. The Gerontologist, 58(2), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw156

Kiyoshi-Teo, H., Carter, N., & Rose, A. (2017). Fall prevention practice gap analysis: Aiming for targeted improvements. MEDSURG Nursing, 26(5), 332–335. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325999697

Lundahl, B., Moleni, T., Burke, B. L., Butters, R., Tollefson, D., Butler, C., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling, 93(2), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012

McMahon, S., Talley, K. M., & Wyman, J. F. (2011). Older people’s perspectives on fall risk and fall prevention programs: A literature review. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 6(4), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2011.00299.x

Miller, W., & Rollnick, S. (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,(3rd edition). The Guilford Press.

Polit, D. F. (1996). Data analysis & statistics for nursing research. Appleton & Lange.

Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

Schepens, S. L., Panzer, V., & Goldberg, A. (2011). Randomized controlled trial comparing tailoring methods of multimedia-based fall prevention education for community-dwelling older adults. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(6), 702–709. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.001180

Söderlund, L. L., Madson, M. B., Rubak, S., & Nilsen, P. (2011). A systematic review of motivational interviewing training for general health care practitioners. Patient Education and Counseling, 84(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.025

Tzeng, H.-M., & Yin, C.-Y. (2015). Patient engagement in hospital fall prevention. Nursing Economic$, 33(6), 326–334. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26845821/

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). (2018). VA nursing academic partnerships. Health Care. https://www.va.gov/oaa/vanap/

VA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. (2011). Clinician Importance and Confidence regarding Health Behavior Counseling [Internal document].

Vogus, T. J., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). The safety organizing scale: Development and validation of a behavioral measure of safety culture in hospital nursing units. Medical Care, 45(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000244635.61178.7a