Postdoctoral fellowship programs play an essential role in developing future leaders in nursing by providing opportunities for interprofessional education, training, and collaboration. Nurse leaders must carefully consider the climate and design of such programs, paying particular attention to the ability to support the career journeys of more doctorally-prepared nurses from diverse backgrounds. This article describes a self-study that considered the unique, yet collective, lived experiences of 11 Black, doctorally-prepared, nurses who completed (or are completing) the same interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship. We describe the study methods, results, discussion, and limitations. Five themes across three phases of the nurse scholars’ educational journeys describe lived experiences in spaces not traditionally designed to support minoritized women, including insight into the limits and benefits of these programs specific to Black nurse scholars. Finally, we suggest implications for nursing to inform interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship programs to strengthen Black nurse scholars as emerging leaders with interprofessional collaboration skills to improve healthcare services provided to diverse patient populations.

Key Words: interdisciplinary education, nursing research, doctorally-prepared nurse, postdoctoral fellowship, Black nurses, Black women, diversity, equity, inclusion, Doctor of Philosophy, PhD in nursing, Doctor of Nursing Practice

...ensuring that these change agents are diverse in thought, experiences, and demographics is of utmost importance.Doctorally-prepared nurses represent only two percent of the nursing workforce (Smiley et al., 2018), yet they are crucial drivers in developing and disseminating scholarship. Most notably, these nurses have the potential to shape nursing practice and quality of healthcare. Thus, ensuring that these change agents are diverse in thought, experiences, and demographics is of utmost importance. Black men and women account for 14% of all 18 to 64-year-old United States residents (United States Census Bureau, 2019), and 17.1% of students in research-focused (e.g., Doctor of Philosophy [PhD]) and practice-focused (e.g., Doctor of Nursing Practice [DNP]) doctorate programs (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2020). Although the number of Black nurse scholars in postdoctoral fellowship programs is unclear, these fellowships remain a critical milestone for shaping career development and advancement.

Postdoctoral Fellowships

Black nurse scholars can utilize these fellowships to build upon the research foundation formed during the doctoral program...Postdoctoral fellowships are short-term transitional training for individuals with a doctoral degree (e.g., Ph.D., MD, DNP, or equivalent) seeking mentored scholarly training to acquire research or professional skills for desired careers (Office of Intramural Training & Education, n.d.). There are roughly 38,500 postdoctoral appointees in the field of science, with 55% of those appointments in biological and biomedical sciences (Kaiser, Bartz, Neugebauer, Pietsch, & Pieper, 2018; Nagelkerk et al., 2018). Although most postdoctoral trainees aspire to pursue academic careers, others seek industry or government careers (Su, 2013).

The postdoctoral training period, also known as “protected time,” allows nurse scholars to increase their research productivity and stand out in competitive academic positions by conducting or leading research projects, publishing papers, and securing grant funding or other resources (Chen, McAlpine, & Amundsen, 2015). This time is crucial for nurse scholars to expand professional networks and establish vital relationships with other scholars and leaders in their respective disciplines (Chen et al., 2015). Postdoctoral fellowships can assist nurse scholars to secure employment at prestigious universities and departments that support their career development (Su, 2013). Lastly, these fellowships prepare nurse scholars for career expectations and responsibilities (e.g., teaching, service, and scholarship).

Postdoctoral fellowships allow nurse scholars to develop independence and build a program of research in their respective academic careers (Rybarczyk, Lerea, Whittington, & Dykstra, 2016). Although this type of fellowship allows nurse scholars to strengthen their research abilities and prepare for careers in academia or other sectors, their experiences and growth rely on the breadth and vision of their mentors (Rice et al., 2020).

Interprofessional Education, Training, and Collaboration

Interprofessional education as defined by the World Health Organization ([WHO], 2010) “occurs when students from two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes” (p.10). Promoting interprofessional education is among the strategic initiative of the AACN (2021). This, and other forms of interdisciplinary training, are critical to equip future healthcare professionals to provide high-quality care and thus are powerful tools to improve healthcare delivery (Dyess, Brown, Brown, Flautt, & Barnes, 2019). A team-based approach to healthcare delivery is essential to effectively care for patients with many comorbidities in an increasingly complex global healthcare setting (Ansa et al., 2020).

Evidence has suggested that interprofessional education has many tangible benefits for students and healthcare users worldwide (Kaiser et al., 2018; WHO, 2010). Students who receive interprofessional education enter the workforce well-equipped to engage in effective communication, conflict resolution, and shared problem-solving on interdisciplinary teams (Dyess et al., 2019; WHO, 2010).

...interprofessional training improves the efficiency of patient care, optimizes patient care decision-making, and increases ethical practice by reducing stereotypical thinking and acknowledging diverse healthcare providers as important and valuableClinicians with interprofessional training have better role clarity, job satisfaction, more positive working environments, and a better sense of well-being on a healthcare team compared to those without interprofessional training (Ansa et al., 2020; WHO, 2010). Additionally, interprofessional training improves the efficiency of patient care, optimizes patient care decision-making, and increases ethical practice by reducing stereotypical thinking and acknowledging diverse healthcare providers as important and valuable (Ansa et al., 2020). Together, interprofessional education and training promote collaboration among clinicians to provide high-quality care and services; improve access and coordination to care across healthcare settings; and increase satisfaction among patients, families, caregivers, and communities across the healthcare continuum (Cino, Austin, Casa, Nebocat, & Spencer, 2018; Dyess et al., 2019; Paige et al., 2014; Renschler, Rhodes, & Cox, 2016; WHO, 2010). Furthermore, interprofessional collaboration among clinicians results in shorter hospital stays, fewer hospital admissions, less staff turnover, and lower patient mortality rates (WHO, 2010).

The WHO (2010) outlines six steps to advance interprofessional education and training: 1) Have a shared vision and purpose for interprofessional education; 2) develop interprofessional education curricula according to principles of good education practice; 3) provide support to develop and deliver interprofessional education and staff training; 4) introduce interprofessional education into healthcare worker continuing education; 5) ensure staff trainers are competent in interprofessional education; and 6) ensure leaders are committed to interprofessional education in educational institutions and practice settings. Given the many benefits of interprofessional training and education, educational institutions must prioritize and take actionable steps to advance interprofessional education and training among clinicians (WHO, 2010).

Information about Black nurse scholars’ experiences in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship may illuminate the limitations and benefits of these training programs in supporting Black nurse scholars during their time as trainees and in research careers. This article will discuss a narrative study to describe the lived experiences of Black doctorally-prepared nurses who are currently enrolled in or who have completed an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship. The fellowship provided mentored health policy and health services research training to physicians and nurses.

Study Methods

Study participants were the author group of this paper, consisting of self-identified Black nurse scholars. Data were collected using an electronic survey, which each participant completed to assess their experiences as postdoctoral fellows in the multisite interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship. Survey items included demographic information such as age, fellowship site, and years as a registered nurse (RN). In addition, eight open-ended questions were used to gather rich descriptions about the benefits and challenges of participating in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship; sources of empowerment during the fellowship; and suggestions for improving the experiences of future Black nurse scholars in these types of programs (see Table 1).

Table 1. Open-ended Questions Related to Black Nurse Scholars’ Experiences in an Interdisciplinary Postdoctoral Fellowship

|

This study was designated as exempt by the Temple University institutional review board. Each survey respondent is an author on this paper, thus informed consent to participate was implied through voluntary authorship. A nurse researcher with expertise in qualitative study design and analysis was also consulted to ensure there were no unintentional ethical research violations in the conduct of this study.

The first author created and disseminated a Qualtrics survey using an anonymous survey link. Demographic data describing characteristics of the nurse scholars were analyzed in Qualtrics. Four authors analyzed the qualitative data using narrative study methods (Creswell, 2013). To assure trustworthiness, member checks were conducted by presenting the identified themes to all authors; group discussion continued until consensus was reached on the emerging themes. Finally, the qualitative research expert was given a draft of the manuscript to review methods and findings; this additional step provided assurance that the study methods were ethically appropriate.

Results: Participant Demographics

Eleven self-identified Black nurse scholars participated in this study (see Table 2 for specific demographics). Five themes emerged from the data. Participant demographics and the themes associated with their experiences in the interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship are described below.

Table 2. Participant Demographics

|

Number |

Percentage |

|

|

Mean Age in Years (SD) 25 to 30-Years-Old |

36.55 3 |

(6.26) 27.3 |

|

Sex (Female) |

11 |

100 |

|

Mean Years as an RN (SD) 1-5 Years |

11 1 |

(4.02) 9.1 |

|

Nursing License Registered Nurse |

6 |

54.6 |

|

Doctoral Degree Doctor of Philosophy |

10 |

90.9 |

|

Fellowship Cohort 2016-2018 |

3 |

27.3 |

|

Fellowship Location East Coast |

5 |

54.5 |

|

Primary Research Role Current Fellow |

4 |

36.4 |

Survey respondents were female nurse scholars (n = 11, 100%) who attended postdoctoral fellowship sites throughout the United States. Most respondents were enrolled in sites located on the east coast (n = 5; 45.5%); only one respondent (9.1%) attended the program in the south. Participants ranged in age from 28 to 47 years (M = 36.6 years); two-thirds were in their 30s (n = 7; 63.6%). The respondents’ years as licensed nurses ranged from four to 16 years (M = 11 years), with more than half having held licenses for 11 to 15 years (n = 6; 54.6%). All respondents were licensed RNs (n = 6; 54.6%) or nurse practitioners (n = 5; 45.5%). One-third of the respondents are current postdoctoral fellows (n = 4; 36.4%), while nearly two-thirds reported having positions as full-time nursing faculty (n = 6; 54.6%); one nurse scholar was working in the private sector (9.1%).

Results: Emerging Themes

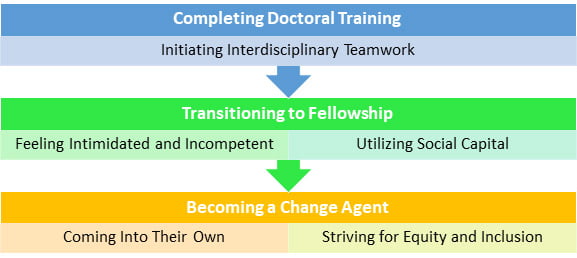

The nurse scholars described their experiences in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship across three phases of their educational journey: Completing Doctoral Training, Transitioning to Fellowship, and Becoming a Change Agent (see Figure). Relevant themes are discussed below within each phase of the educational journey and are presented, followed by relevant participant quotes in Table 3. The nurse scholars describe their experiences in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship across three phases of the educational journey, which are depicted in the Figure below. These phases included, Completing Doctoral Training, Transitioning to Fellowship, and Becoming a Change Agent. The figure aligns these phrases with the five emerging themes described below.

Figure. Phases of Black Nurse Scholars’ Educational Journey through an Interdisciplinary Postdoctoral Fellowship

Completing Doctoral Training

Initiating Interdisciplinary Teamwork. The doctoral programs in which the nurse scholars participated were crucial for exposure to interdisciplinary collaborations and preparation for interdisciplinary postdoctoral Most nurse scholars described how they engaged in interdisciplinary research teams and established mentorships with researchers outside of nursing...fellowships. Most nurse scholars described how they engaged in interdisciplinary research teams and established mentorships with researchers outside of nursing during their doctoral programs. Interdisciplinary collaborations occurred through coursework, research projects, and summer internships, giving nurse scholars frequent opportunities to gain knowledge about the research process through the perspectives of various disciplines. Some participants also expressed how engaging in interdisciplinary opportunities in their doctoral programs provided a sense of empowerment to intentionally seek interdisciplinary collaborations in their postdoctoral fellowship.

Transition to Fellowship

Despite feeling qualified, some shared feelings of intimidation—often identified as imposter syndrome.Feeling Intimidated and Incompetent. In general, respondents felt qualified for the interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship. Their qualifications were attributed to having esteemed mentors, strong recommendation letters, past research experience, and an eagerness and motivation to learn. Despite feeling qualified, some shared feelings of intimidation—often identified as imposter syndrome. Several scholars described feeling incompetent due to their doctoral institution being perceived as less prestigious than their postdoctoral institution. They also expressed this concern when coming from a teaching institution or a historically Black college/university (HBCU) to an Ivy league or research-intensive institution.

Utilizing Social Capital. Survey respondents discussed the importance of social support of mentors or family and friends, which often began during their doctoral programs. Mentors typically worked outside of the scholars’ departments or institutions. They provided a safe space for scholars to discuss their experiences and receive guidance on moving forward in their career journeys. This support helped the scholars increase their confidence in their ability to excel in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship.

Mentors typically worked outside of the scholars’ departments or institutions. Although scholars shared experiences of being Black women in academia with their mentors, the family and friends who supported them did not always share in this experience. Nonetheless, these friends and family celebrated the scholars’ accomplishments as expected milestones when colleagues and academic superiors evaluated them. For one respondent, social support also came with financial backing that helped her move across the country to pursue the fellowship.

Becoming a Change Agent

Coming Into Their Own. The nurse scholars expressed appreciation for the interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship that helped expand their knowledge and perspectives of career options outside of the nursing profession. Many saw a diversity of thought as a benefit of participating in the postdoctoral fellowship. Some appreciated the ease of access to various perspectives when collaborating with clinicians and researchers in numerous disciplines. They expressed how they expanded their knowledge of research methods, healthcare issues, and potential career options beyond nursing and academia through exposure to other healthcare disciplines. They also believed that participating in a non-traditional postdoctoral fellowship facilitated respect and improved their relationships with physician colleagues.

Many saw a diversity of thought as a benefit of participating in the postdoctoral fellowship. Before entering the fellowship, many nurse scholars believed they were limited to academic positions in nursing. However, after fellowship completion, some sought careers in non-nursing departments (e.g., medicine, public health, and non-clinical fields such as business and policy advocacy). Integral to seeking career options outside of nursing were interdisciplinary mentors; Black mentors who resonated with the scholars’ experiences in academia; and knowledge of nurses’ roles and contribution in other disciplines. Completing the postdoctoral fellowship also helped nurse scholars overcome their fear of the nurse-physician power dynamic and empowered them to collaborate with researchers across disciplines.

Striving for Equity and Inclusion. Although the nurse scholars reported the benefits of interdisciplinary postdoctoral training, they also communicated their frustrations with the minimal inclusion of doctorally-prepared nurses. With this lack of equal nurse and physician scholar representation, some nurses reported experiencing their colleagues’ “resistance to the flattened power dynamic,” leading to the belief that these physicians valued nurses’ perspectives less than perspectives of other physicians. Other nurse scholars felt that physician members of their cohort were supportive and provided a safe space to express any self-identified inadequacies.

Participants also expressed the importance of postdoctoral fellowships increasing the diversity of scholars, faculty, and guest lecturers. Many participants identified the need for an anti-racist curriculum to educate all scholars in conducting decolonized research that does not cause or perpetuate the harm already inflicted upon marginalized groups. Participants also expressed the importance of postdoctoral fellowships increasing the diversity of scholars, faculty, and guest lecturers. They believe that program administrators should enhance efforts to recruit scholars from all marginalized groups. They also suggested that interdisciplinary fellowships ensure faculty and guest lecturers represent marginalized groups and/or actively engage in anti-racism work.

Table 3. Themes Describing Black Nurse Scholars’ Experiences in an Interdisciplinary Postdoctoral Fellowship

|

Themes |

Supporting Quotes |

|

Initiating Interdisciplinary Teamwork |

“Our [doctoral] curriculum was designed to have coursework outside of our discipline (e.g., public health, medicine, psychology, social work) … you would have the opportunity to work with individuals from varied disciplines.” “During my predoc, I was exposed to and conducted research with a variety of individuals from various disciplines, including nursing, psychology, medicine, music therapy, biostatistics, social work, divinity, and health communication. This positioned me well to work on interdisciplinary teams as a PhD-prepared nurse.” “My doctoral experience had limited exposure to interdisciplinary opportunities because I was not on a T32 where that experience was required.” |

|

Feeling Intimidated and Incompetent |

“I didn't know if I would be accepted at such a prestigious university. Having never attended an Ivy League university, I was quite intimidated.” “I didn't feel competent in research nor thought of myself highly [enough] to be considered for such a prestigious program... I guess imposter syndrome played a role.” “My cohort is an amazing group that created a safe space for each of us early on to express when we weren't feeling smart enough, lost in terms of what we should be doing in the program, and clueless on what we want to do with our research projects.” |

|

Utilizing Social Capital |

“[I was empowered by] finding a group of women of color in academia who I can discuss my challenges within a safe space and speak my mind without ‘code-switching.’” “In my postdoc, mentorship continued to play a solid role in my development as a professional in specific [sic] research area. My mentor encouraged me to strive to become a thought leader and helped me to apply to the [interdisciplinary postdoc].” “Social support played a huge role, whether that came from mentors and classmates in academia, or family and friends… having social support helped me stay grounded and reminded me of how far I've come, while helping me stay encouraged and motivated to keep going.” |

|

Coming into Their Own |

“I learned that the power dynamic between nurses and physicians was a facade and that I am more than capable of sitting at any table I am invited to. I no longer have a fear of working with health care researchers outside of nursing.” “The interdisciplinary postdoc spurred additional professional curiosity, which likely wouldn't have been the case in a traditional nursing postdoc.” “I felt even more prepared because my physician cohorts didn’t have nearly as much experience conducting research. I felt like I had an extreme advantage and could hit the ground running in making connections and thinking about projects to be a part.” |

|

Striving for Equity and Inclusion in Interdisciplinary Spaces |

“The biggest drawback is that [sic] not having enough nursing representation in the program.” “Decolonize the assumptions, methods, interpretations, and ahistorical thinking that frustrates and burdens our experiences.” “Increasing diversity is always beneficial to any academic program. Having representation from underrepresented minorities would have enhanced the program for me.” |

Discussion

Five themes emerged from Black nurse scholars’ experiences in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship, across three phases of their educational journeys. All educational experiences were relevant to the career advancement and challenges experienced by each individual. Respondents expressed that interprofessional education is a powerful tool. Course work and other group training provided an avenue for these scholars to gain additional knowledge and add to the collegial discussions about the research process from their peers across disciplines. Additionally, collaborative approaches such as these in education help to expand and appreciate diverse experiences.

The literature shows that conducting collaborative scholarship in partnership with varying fields and the community can identify inequities, value multiple ways of knowing, organize efforts to build a power of change, and produce high-quality research (Warren, 2018). A signature feature of the nurse scholars’ interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship was to create change agents in healthcare. The scholars voiced that while these interactions were vital, institutions and programs must be prepared to level up, revise traditional teaching pedagogies, and train scholars to navigate partiality and the other aspects that may come with healthcare, research, and reform.

Black nurse scholars’ perspectives and experiences are needed to inform policy change...Being a Black nurse scholar in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship presents doctorally-prepared nurses with opportunities to collaborate with researchers of various disciplines and address important health disparities. This collaborative approach is beneficial for those interested in public policy careers to advocate for social justice and health equity. Black nurse scholars’ perspectives and experiences are needed to inform policy change, but they must be prepared and trained to navigate partisanship and the nuances associated with healthcare reform. Through mentorship and projects, Black nurse scholars develop and strengthen these skills.

Other themes identified to help advance Black nurse scholars included social support and mentorship.Additionally, nurse scholars can conduct community-based participatory or interdisciplinary research projects with community members and organizations who serve the community. These dynamic collaborations provide nurse scholars with varied perspectives from people outside of academia and nursing and the ability to mutually exchange information to develop and implement interventions with those living in the communities that the intervention impacts. Other themes identified to help advance Black nurse scholars included social support and mentorship. Social support can consist of family, friends (academic and longtime), and faculty.

The literature has shown that graduate students are significantly more stressed than the general public due to the intensity of their academic programs; building and maintaining new relationships; creating their professional identity; and feeling isolated (Jairam & Kahl, 2012). Here, we show that Black scholars had family and friends present to celebrate their accomplishments; these supporters were integral in the success of their path in all levels of their education and fostering social capital. In addition, mentors (formal and informal) who were genuinely vested in them helped increase confidence and provided a safe space for scholars to discuss personal and academic experiences even after completing their degrees.

...while social support, collaboration, and building social capital were facilitators in their success...the participants also described barriers.In contrast, while social support, collaboration, and building social capital were facilitators in their success, in this study the participants also described barriers. The application process, imposter syndrome, and the need for a more inclusive curriculum with various disciplines were themes that overshadowed these experiences. In 2020, the repeated images of police brutality against Black people and the magnification of structural racism across the United States sparked a movement demanding social justice. Some nursing or healthcare industry organizations and hospitals raced to publish statements denouncing racism, vowing to increase diversity within their workforce, and implement initiatives to address discrimination within their establishments. Universities and agencies that offer postdoctoral fellowships are not immune from this culture shift. Although this article reports the experiences of Black nurse scholars in an interdisciplinary fellowship, there needs to be systemic changes in which traditionally white systems and institutions can support nurse scholars from marginalized communities.

In all, we know that postdoctoral fellowships have traditionally helped widen the research pipeline, make candidates more competitive for jobs, foster positive attitudes toward other disciplines, and improve research skills (Gennaro, Deatrick, Dobal, Jemmott, & Ball, 2007). Minor revisions, such as offering separate program pathways that consider and respect nurse scholars' level of knowledge and experience, can offer an even more impactful steppingstone to any scholar's success.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, all of the Black nurse scholars who participated in this study were female. Their interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship has not enrolled any Black male nurse scholars during its six-year existence. The dearth of male presence is consistent with the noted lack of men in nursing, in general, and in nursing PhD programs, specifically (National League for Nursing, 2021; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). The gender disparity identified in this study highlights the persistent need for increased intentionality in recruiting male nurses to nursing research doctorates and postdoctoral fellowship programs.

Further, the authors conducted a self-administered survey and were participants in this study, which may introduce potential bias and a conflict of interest. Potential bias was mitigated by consulting with a researcher with qualitative expertise at various points throughout data collection, analysis, and dissemination. However, describing the lived experiences of Black nurse scholars in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship provides insight into a lesser explored area in interprofessional education and provides varied perspectives of Black nurse scholars’ experiences in a single postdoctoral program.

In addition, some participants' may have felt reluctant to share their experiences as scholars; however, all scholars’ survey responses were presented anonymously. Nonetheless, the information presented here is novel, gives a voice to the Black nurse scholar experience, and captures the diversity of experiences in academic settings that is not widely expressed within the literature. Still, transferability of the findings cannot be applied to nurse scholars in other postdoctoral fellowships or similar research training programs, or those who attend other educational institutions.

Implications for Nursing

Black nurse scholars’ perspectives and experiences are needed...but they must be prepared and trained to navigate partisanship and the nuances associated with healthcare reform.Being a Black nurse scholar in an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship presents doctorally-prepared nurses with opportunities to collaborate with researchers of various disciplines and address issues in healthcare. This collaborative approach is beneficial for those interested in public policy careers to argue for social justice and health equity. Black nurse scholars’ perspectives and experiences are needed to inform policy change, but they must be prepared and trained to navigate partisanship and the nuances associated with healthcare reform. Through mentorship and projects completed during an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship, Black nurse scholars can develop and strengthen these skills.

Our findings may help higher education institutions anticipate what is required to promote diversity and interdisciplinary collaboration and education in terminal degree, professional, and postdoctoral programs. For this article, the experiences of Black nurses in interdisciplinary postdoctoral education is novel. Our experiences are diverse, unique, lived, and should be leveraged ideally in both healthcare and educational settings.

Our experiences are diverse, unique, lived, and should be leveraged ideally in both healthcare and educational settings.Relevant to nursing, our findings suggest that university administrators should prioritize ongoing mentorship from diverse faculty to bolster the success of postdoctoral scholars. Mentorship provides a strong foundation for early-career nurse scholars to advance their research programs by exposure to opportunities to access informal networks; professional development opportunities such as academic publishing; and promoting confidence and social support. In particular, publications and participation by nurses of color in these types of activities can encourage exposure to racially diverse experiences and specific nursing knowledge and interpretation of our phenomena (Conn et al., 2019).

Relevant to interdisciplinary networks and education, institutions and mentors should cultivate opportunities for early-career Black nurses to participate in interdisciplinary teams. These experiences allow nurses to better understand and practice articulating their expertise and health equity perspective with other disciplines. In turn, interdisciplinary teams become more aware of nurses’ clinical and research skills and can best determine how to integrate their views to improve research design and clinical operations. Practical knowledge about nurses' research, training, and lived experiences strengthens these programs and fosters a culture of everyday inclusion at these institutions.

...institutions and mentors should cultivate opportunities for early-career Black nurses to participate in interdisciplinary teams.Positive discourse among intra- and interdisciplinary spaces may also improve care across healthcare settings and reduce alienation among students and faculty from marginalized groups in predominately White institutions (Montgomery, Bundy, Cofer, & Nicholls, 2021). To this point, improving communication, publishing in other disciplines, increasing a diverse applicant pool, and curriculum revision can foster change in nursing and other disciplines to achieve equity in higher education.

Finally, our study was non-traditional, yet innovative in its design. The authors conducted a self-administered survey. Typically, researchers analyze data gathered by participants that do not include the study investigators or manuscript authors. Some may identify this method of inquiry as a largely biased methodology. However, it is widespread knowledge that underrepresented and historically excluded communities are often the population of interest of scholars within their own communities. As we continue to reimagine the ways in which research is conducted and by whom, we support the creation of new methodologies and guidelines to aid authors who are members of marginalized communities in the ethically appropriate collection, analysis, and publication of their personal data as a method of scholarly inquiry and dissemination.

Conclusion

Creating diverse postdoctoral fellowships requires intentional efforts to support historically underrepresented groups. To engage in interprofessional collaboration, nurse scholars must learn from and work with colleagues from diverse backgrounds, including all racial, ethnic, sexual orientation, and gender identities to address varied needs of the populations served. The authors not only have first-hand experience as nurse scholars of a nationally recognized, interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship program, they are also Black women pursuing careers in either academia, government, or private industry. The intersection of their racial and gender identities allows them to empathize with one another and enthusiastically celebrate their victories in pursuing a career in nursing, considering its underrepresentation of women of color. Although, the participants are individuals with their own lived experiences, their shared identities facilitate a bond and sense of support that is authentic, sincere, and necessary in postdoctoral fellowships, where they are often also underrepresented. Increased representation of marginalized groups creates a safe space and sense of belonging in both doctoral and postdoctoral programs.

Creating diverse postdoctoral fellowships requires intentional efforts to support historically underrepresented groups. Our findings emphasize promising outcomes of acknowledging lived experiences, particularly of marginalized groups, when designing interprofessional educational programs. Thus, doctorally-prepared Black nurse scholars should be valued and supported throughout their interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellowship and into their careers as nurse scientists.

Authors

Tiffany M. Montgomery, PhD, MSHP, RNC-OB

Email: Tiffany.M.Montgomery@temple.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-4990-146X

Dr. Tiffany M. Montgomery is an assistant professor in the Temple University College of Public Health, Department of Nursing, where she studies sexual and reproductive health disparities, as well as diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in nursing education. She received a PhD in Nursing from the University of California, Los Angeles, Master of Science in Health Policy Research from the University of Pennsylvania, Master of Science in Nursing Education from California State University, Dominguez Hills, and Bachelor of Science in Nursing and minor in African-American Studies from San Jose State University. Her DEI work and expertise in Black women supported her selection as first author of this manuscript.

Kortney Floyd James, PhD, RN, PNP-C

Email: KFJames@mednet.ucla.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-6182-8501

Dr. Kortney Floyd James is a nurse scientist and Pediatric Nurse Practitioner. She holds a PhD in Nursing from the Byrdine F. Lewis College of Nursing & Health Profession at Georgia State University. Dr. Floyd James is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of California, Los Angeles. During this Fellowship, Dr. Floyd James will continue to focus on the physical and mental health of Black mothers by assessing the ways that clinical practice and policy change can meet their needs, while also considering the unique cultural influences on their health. Throughout her academic and nursing career she has navigated interdisciplinary spaces and therefore, capable to provide insight and lived experiences regarding this work.

Lisa N. Mansfield, PhD, RN

Email: lmansfield@mednet.ucla.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-4617-2663

Dr. Lisa Mansfield obtained a Bachelor of Science in Nursing and Master of Science in Nursing Education from Winston-Salem State University. She received a Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing degree from Duke University School of Nursing. She is currently a second-year postdoctoral fellow in the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of California, Los Angeles which informed the experiences discussed in this paper.

Morine Cebert Gaitors, PhD, FNP-C

Email: morine.cebert@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3440-2089

Dr. Morine Cebert Gaitors is a post-doctoral fellow through the National Clinicians Scholars Program at the University of Pennsylvania. She earned a Bachelor of Nursing Science from Boston College, Family Nurse Practitioner certificate from Winston-Salem State University, and PhD from Duke University where she was a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholar. Her current work examines provider referral patterns of women presenting to primary care with reproductive endocrinology concerns and is funded by the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics. Dr. Gaitors also serves as the health disparities sub-committee chair for the American Society of Reproductive Medicine's Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Taskforce and is a founding member of RESOLVE's Diversity and Inclusion Council. These experiences lend to her first-hand experiences which she used to write this paper.

Jade C. Burns, PhD, RN, CPNP-PC

Email: curryj@umich.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-2434-6829

Dr. Jade C. Burns is an assistant professor at the University of Michigan School of Nursing. Her research focuses on innovative approaches using community-engaged research and technology (e.g., social media, messaging, digital spaces) to increase access to sexual health services for adolescents and young adults in community health centers. Dr. Burns’ expertise in clinical practice as a pediatric nurse practitioner is adolescent healthcare, family planning, health promotion, and HIV/STI prevention. Her secondary area of interest include is improving nursing practice and training programs in underserved areas. Burns holds a Bachelor of Science in Nursing from the University of Michigan, a Master of Science degree in Nursing (pediatric nurse practitioner, primary care) from the University of Pennsylvania, a Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing degree from the University of Michigan and completed a postdoctoral fellowship in health policy with the National Clinician Scholars Program.

Jasmine Travers, PhD, MHS, AGPCNP-BC

Email: jt129@nyu.edu

ORCID ID: 000-0003-3327-5062

Dr. Jasmine Travers is an assistant professor at New York University Rory Meyers College of Nursing. Her career is dedicated to designing and conducting research to improve health outcomes and reduce health disparities in vulnerable older adult groups using both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Over the years, Dr. Travers has built a strong foundation to address the health and well-being of a rapidly growing, diverse older adult population requiring long-term care. As a health services researcher, she has leveraged many datasets to investigate these issues and has published widely on the topics of aging, long-term care, health disparities, workforce issues, and infections. Prior to joining the faculty at NYU, Dr. Travers completed a postdoctoral fellowship with the National Clinician Scholars Program at Yale University and a T32 funded postdoctoral fellowship at the New Courtland Center for Transitions and Health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing; she completed doctoral training in health services research with a specialization in gerontology at Columbia University School of Nursing.

Esther Laury, PhD, RN

Email: esther.laury@merck.com

ORCID ID:

Dr. Esther R. Laury is an associate director of policy research at Merck, conducting research on a number of areas within healthcare delivery. Prior to joining Merck, Dr. Laury was a long-term care charge nurse and an assistant professor at the Louise M. Fitzpatrick College of Nursing at Villanova University. Preceding her time at Villanova University, she was the Dean’s Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. She was also a National Clinician Scholar and a student in the Master of Science in Health Policy Research program at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. She completed a PhD in Nursing Science at Indiana University in Indianapolis, IN.

Cherie Conley, PhD, MHS, RN

Email: chconley@umich.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-6142-5852

Dr. Cherie Conley completed a PhD in Nursing, with a focus on community health, at Duke University School of Nursing. She received a bachelor’s degree from Spelman College and Master’s degree in Disease Control and Prevention at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. As a doctoral student, Dr. Conley co-led an interdisciplinary team of students and family medicine residents to promote physical activity on the Duke University Campus and Durham Community. She is part of an interdisciplinary cohort of National Clinician Scholars and is currently collaborating with a community organization to improve HIV prevention for Black women.

Keitra Thompson, DNP, MHS, APRN

Email: keitra.thompson@yale.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-6953-4364

Dr. Keitra Thompson is an associate research scientist at Yale School of Public Health working to address the impact of poverty and mental health on the well-being of women and children. As a dually board-certified family and psychiatric nurse practitioner she combines clinical experiences with advanced mixed methods research training to advance health equity.

Dominique Bulgin, PhD, RN

Email: dbulgin@utk.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-4030-0791

Dr. Dominique Bulgin is an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville College of Nursing. She obtained a BSN from Emory University and PhD from Duke University. Dr. Bulgin also completed the National Clinician Scholars Program at Duke University School of Nursing. Dr. Bulgin’s background includes conducting both primary data collection and secondary analyses of preexisting datasets to explore factors that influence health behaviors, domestically and globally. Her experience completing an interdisciplinary postdoc and collecting and analyzing qualitative data have prepared her to co-author this manuscript.

Kia Skrine Jeffers, PhD, RN, PHN

Email: kiajeffers@ucla.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-6162-3071

Dr. Kia Skrine Jeffers is an assistant professor in the UCLA School of Nursing and Associate Director for the Arts in the Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice & Health in the Fielding School of Public Health at UCLA. She is also a practicing community-based Registered Nurse with a Public Health Nursing certification from the CA Board of Registered Nursing. Most of her research and clinical work has been with adults and families who are members of racial/ethnic minority groups. She is interested in identifying ways that structural factors (e.g., structural racism) get embodied and developing interventions to mitigate the impact that health inequity has on individuals’ cardiometabolic and mental health. Her work has a strong community-focused orientation that centers heavily upon the lived of experiences of individuals and communities using both qualitative and quantitative research designs.

References

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2020). Race/ethnicity of students enrolled from generic (entry-level) baccalaureate, RN-to-baccalaureate, total baccalaureate, master’s, research-focused doctoral, and DNP programs in nursing, 2010-2019 (Table). Surveys-Data. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/News/Surveys-Data/EthnicityTbl.pdf

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2021). Interprofessional Education. Initiatives. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Interprofessional-Education

Ansa, B. E., Zechariah, S., Gates, A. M., Johnson, S. W., Heboyan, V., & De Leo, G. (2020). Attitudes and behavior towards interprofessional collaboration among healthcare professionals in a large academic medical center. Healthcare, 8(3), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030323

Chen, S., McAlpine, L., & Amundsen, C. (2015). Postdoctoral positions as preparation for desired careers: A narrative approach to understanding postdoctoral experience. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(6), 1083–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1024633

Cino, K., Austin, R., Casa, C., Nebocat, C., & Spencer, A. (2018). Interprofessional ethics education seminar for undergraduate health science students: A pilot study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(2), 239–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1387771

Conn, V. S., McCarthy, A. M., Cohen, M. Z., Anderson, C. M., Killion, C., DeVon, H. A., Topp, R., Fahrenwald, N. L., Herrick, L. M., Benefield, L. E., Smith, C. E., Jefferson, U. T., & Anderson, E. A. (2019). Pearls and pitfalls of team science. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 41(6), 920–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945918793097

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Dyess, A. L., Brown, J. S., Brown, N. D., Flautt, K. M., & Barnes, L. J. (2019). Impact of interprofessional education on students of the health professions: A systematic review. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 16, 33. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2019.16.33

Gennaro, S., Deatrick, J. A., Dobal, M. T., Jemmott, L. S., & Ball, K. R. (2007). An alternative model for postdoctoral education of nurses engaged in research with potentially vulnerable populations. Nursing Outlook, 55(6), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2007.08.005

Jairam, D., & Kahl, D. H. (2012). Navigating the doctoral experience: The role of social support in successful degree completion. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7, 311–329. https://doi.org/10.28945/1700

Kaiser, L., Bartz, S., Neugebauer, E. A. M., Pietsch, B., & Pieper, D. (2018). Interprofessional collaboration and patient-reported outcomes in inpatient care: Protocol for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0797-3

Montgomery, T. M., Bundy, J. R., Cofer, D., & Nicholls, E. M. (2021, February 1). Black Americans in nursing education. American Nurse, 16(2), 22-25. https://www.myamericannurse.com/black-americans-in-nursing-education/

Nagelkerk, J., Thompson, M. E., Bouthillier, M., Tompkins, A., Baer, L. J., Trytko, J., Booth, A., Stevens, A., & Groeneveld, K. (2018). Improving outcomes in adults with diabetes through an interprofessional collaborative practice program. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1372395

National League for Nursing (NLN). (2021). Nursing education statistics. Newsroom. http://www.nln.org/newsroom/nursing-education-statistics

Office of Intramural Training & Education. (n.d.). Postdoc FAQs. National Institutes of Health. https://www.training.nih.gov/resources/faqs/postdoc_irp

Paige, J. T., Garbee, D. D., Kozmenko, V., Yu, Q., Kozmenko, L., Yang, T., Bonanno, L., & Swartz, W. (2014). Getting a head start: High-fidelity, simulation-based operating room team training of interprofessional students. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 218(1), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.09.006

Renschler, L., Rhodes, D., & Cox, C. (2016). Effect of interprofessional clinical education programme length on students’ attitudes towards teamwork. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(3), 338–346. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2016.1144582

Rice, M., Davis, S. L., Soistmann, H. C., Johnson, A. H., Gray, L., Turner-Henson, A., & Lynch, T. (2020). Challenges and strategies of early career nurse scientists when the traditional postdoctoral fellowship is not an option. Journal of Professional Nursing, 36(6), 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.03.006

Rybarczyk, B. J., Lerea, L., Whittington, D., & Dykstra, L. (2016). Analysis of postdoctoral training outcomes that broaden participation in science careers. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-01-0032

Smiley, R. A., Lauer, P., Bienemy, C., Berg, J. G., Shireman, E., Reneau, K. A., & Alexander, M. (2018). The 2017 National Nursing Workforce Survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 9(3), S1–S88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(18)30131-5

Su, X. (2013). The impacts of postdoctoral training on scientists’ academic employment. The Journal of Higher Education, 84(2), 239–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2013.11777287

United States Census Bureau. (2019). Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, race alone or in combination, and Hispanic origin: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018. Data. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-detail.html

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. CPS Overview. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

Warren, M. R. (2018). Research confronts equity and social justice–Building the emerging field of collaborative, community engaged education research: Introduction to the special issue. Urban Education, 53(4), 439–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918763495

World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice (WHO/HRH/HPN/10.3). World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70185