The Brazilian first republic sought to organize society and amplify its potential for political and economic development, an objective hindered by the precarious health conditions of a population devastated by epidemics. An alliance between Brazil and the United States, mediated by the Rockefeller Foundation, gave birth to the arrival of Ethel Parsons in Brazil and the Parsons Mission, which developed strategies to implant a model for raising the standards of nursing in Brazil. This article offers background information about the Parsons Mission, and discusses its impact in public health and nursing education. History shows that the creation and organization of a public nursing health service, in addition to a nursing school based on Anglo-American models, were successful strategies in the construction of a new professional identity for nurses and for the recognition of nursing as a female profession.

Key Words: Nursing history; public health nursing, international technical cooperation; Rockefeller foundation, history of public health, health visitors, home nursing, nursing professionalization, nursing education, professional identity

Brazil entered the twentieth century as a young republic, starting a new era of political, economic, and social development. Due to its large territory, its time as a Portuguese colony (1500-1815), and its condition as the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery (1888), it faced many problems to achieve the development its leaders sought. Positivistic ideals, which put scientific knowledge above religion, started to guide ideas in Brazilian society. This led to an increase in sciences and academic education. Scientific innovations were starting to be sought in the United States rather than in France, a country whose illuminist ideas had, throughout the 19thcentury, influenced Brazilian architecture, arts, and medicine (Lima, Fonseca & Hochman, 2005).

Brazil suffered from great epidemics caused by Spanish flu, tuberculosis, smallpox, and typhus. Brazil suffered from great epidemics caused by Spanish flu, tuberculosis, smallpox, and typhus. These diseases spread due to extremely poor hygiene practices by the population, and the often deadly unsanitary conditions of the cities. Even Rio de Janeiro, the capital of the young Federative Republic of Brazil, had massive public health and hygiene issues as its main concerns. It was essential for the government to deal with these challenges to achieve economic development (Souza, 2008).

The Brazilian first republic sought to organize society and amplify its potential for political and economic development, an objective hindered by the precarious health conditions of a population devastated by the epidemics. An alliance between Brazil and the United States, mediated by the Rockefeller Foundation, gave birth to the Parsons Mission, which developed strategies to implement a model to raise the standards of nursing in Brazil. This article offers background information about the Parsons Mission and describes its impact in public health and nursing education.

Background of the Parsons Mission

Brazilian physicians had a strong reputation in the field of sanitary medicine, especially with regard to tropical diseases typical to the Mata Atlântica region. Yellow fever had been controlled by the Brazilian scientist Oswaldo Cruz in 1909. His successor, the sanitary physician and scientist Carlos Chagas who was internationally known for his discovery of the Chagas disease, followed his footsteps in the fight against epidemics. Chagas sought to offer better health conditions for the population. To do so, he formed an alliance with the United States (US) in the 1920s (Castro-Santos & Faria, 2003; Santos, 2004).

The Brazil-U.S. alliance was useful for both countries. The Brazil-U.S. alliance was useful for both countries. For Brazil, the health benefits were many, while for the US, the alliance was an opportunity to gain access to a country of continental dimensions which shares borders with nearly all countries in South America. This allowed for economic and research-related activities, especially in preventive medicine. To support this relationship, the Rockefeller Foundation sent a medical mission to Brazil in 1916, which aided the implementation of hygiene and disease prevention measures in rural areas. These measures addressed with endemic diseases, such as malaria, hookworm infections, and Chagas disease. The goal was to improve the health and healthcare of the population, while researching tropical diseases that affected a great portion of the Brazilian agricultural workforce and prejudiced the exchange of goods between the countries (Campos, Cohn & Brandão, 2016; Miyamoto, 2017).

Sanitary surveillance professionals worked with physicians and were known as nursing visitors. Sanitary surveillance professionals worked with physicians and were known as nursing visitors. They were women who worked in patient homes, aiding in the dissemination of prophylactic measures according to the hygiene ideology. For example, they would carry out activities in public institutions to prevent transmissible diseases in adults and children, including physical examinations, vaccinations, guidance regarding body hygiene, and hygienic habits during meals. They were also in charge of checking the children for pathological conditions or organic anomalies and for taking any measures necessary with regards to hygiene problems in the community (Faria, 2006)

Poor patients were not just regarded as problematic to the organization of work and the maintenance of public order, but also as threats of contamination. The visitors went to the poorest neighborhoods to put an end to epidemics and to the propagation of vices, in addition to offering guidance for a life with less risks of contamination (Bonini et al., 2015; Chalhoub, 1996).

Their rudimentary educational levels and health meant [nursing visitors] were not perceived as trustworthy by the families who received their visits. However, the idea to use these nursing visitors was flawed. Their rudimentary educational levels and health meant they were not perceived as trustworthy by the families who received their visits. This lead Carlos Chagas, then director of the National Department of Public Health (DNSP), to support a change in Brazilian nursing. In the past, nursing care was performed by different groups, including religious women, ex-slaves, and nurses who graduated from schools that were not in accordance to Anglo-American teaching standards. Anglo-American nursing schools promoted the idea that nursing schools should only accept women with high moral standards, who would live in the school and be submitted to severe disciplinary rules (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999). Both schools in Rio de Janeiro were directed by male physicians and no professors were nurses.

In the nineteenth century, the Anglo-American model had been brought to the Samaritan Hospital in the city of São Paulo; however, training there was exclusive to English women and their daughters. They completed a probationary period and had to present acceptable levels of education and physical strength. The training lasted for three years. Nurses lived and studied within the hospital, which was, for them, both hospital and boarding school. These nurses did not circulate in society; the school aimed for them to act exclusively inside the Samaritan hospital (Carrijo, Oguisso, & Campos, 2010; Mott, 1999).

Both schools in Rio de Janeiro were directed by male physicians and no professors were nurses.Chagas was invited to the US by the Rockefeller Foundation, where he visited hospitals and public health services in Texas, New York, and Pennsylvania. After seeing their work, he became interested in the idea of bringing U.S. nurses to Brazil, to aid in the sanitary reform. Encouraged by the Rockefeller Foundation, he sought cooperation from its International Health Board to establish the Technical Cooperation Mission for the Teaching of Nursing in Brazil (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999). After formalizing the Mission, the Rockefeller Foundation hired public health nurse Ethel Parsons, then Director of the Child Hygiene Department in Austin, Texas, to lead what is today known as the Parsons Mission.

The Parsons Mission aimed to create a nursing school in Brazil with the structure of North American schools and to organize the Public Health Nursing Service of the DNSP. Ethel Parsons arrived in Brazil in 1921 to assess the current situation of the nursing profession in the country, and concluded that there were no professional nurses who met the standards of schools in the United States. Brazil was not yet using Anglo-American nursing educational methods, something Parsons immediately reported to the Rockefeller foundation. This alone demonstrated the importance of the Parsons Mission to lead the development of the healthcare field in Brazil (Moreira, 1921).

The Parsons Mission aimed to create a nursing school in Brazil with the structure of North American schools...The Parsons Mission lasted from 1921 to 1931, and included 33 nurses. Most of them were from North America and all had graduated and/or post-graduated from American nursing programs (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999). The next section will describe features of Anglo-American nursing education that were incorporated by the Technical Cooperation Mission for the Teaching of Nursing in Brazil (Parsons Mission). The discussion begins with the arrival of Ethel Parsons in Brazil in 1921 and continues to the graduation of the first class of nurses from the DNSP School for Nurses in 1925.

The Parsons Mission and Public Health

Parsons had a long career in public health. She was a Red Cross nurse and, at the Rockefeller Foundation, was part of a mission in Mexico, where she became proficient in Spanish (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999). Upon arrival in Brazil, she conducted a survey of the nursing services in the country (Moreira, 1921). This assessment reiterated the need to implement a new model of nursing education, similar to the American model. The Brazilian public needed to recognize the value of nurses. Practical activities in the area of public health demonstrated the nurses' knowledge and potential to work and teach (Moreira, 1921).

The Brazilian public needed to recognize the value of nurses.Parsons wrote a careful report to the Rockefeller Foundation, informing them about the absence of adequate institutions to train nurses and noting that the institutions were near the most minimal standards recognized in Anglo-Saxon countries (Moreira, 1921). Her records stated that most hospitals in Rio de Janeiro were well-built, but overcrowded. Regarding the healthcare team, she noted that physicians were curious and nurses were from both genders and unprepared (Moreira, 1921).

Parsons found poor conditions and criticized the fact that, in the DNSP, 44 women were prepared for the role of sanitary visitors, also known as visitor nurses, in a 12-hour course taught by physicians. Parsons believed that this was not enough to provide them with sufficient knowledge to detect new cases of tuberculosis and guide the diseased and their families. Thus would not diminish the risk of further infections and promote better quality of life. She highlighted that these women were completely unqualified, lacked field training, and were not prepared to represent the sanitary authority (physicians) in their house visits (Bonini et al., 2015; Moreira, 1921). Public health authorities used home visits to impact the health of poorer populations; introduce healthier habits; and guarantee the health of the workforce in factories and services responsible to maintain the economy of the capital of the country. Parsons’ evaluation, based on North American standards, noted that sanitary visits were extremely unsatisfactory and unable to support positive impacts in the health of the population (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999).

...the immediate problem was training the sanitary visitors without interrupting their work. For Parsons, the immediate problem was training the sanitary visitors without interrupting their work. They needed precise guidance that could be understood by people with lower educational levels, since many were illiterate. The supervision the North American nurses gave to the visitors established a relationship of trust with the families, while establishing the high nursing standards practiced in the United States. This ultimately led the DNSP doctors to conclude that these standards were both essential and feasible (Moreira, 1999; Moreira, 1921).

Parsons was the leader of the Mission for the Development of Nursing in Brazil and was named Superintendent of the Nursing Service at the DNSP. She used two strategies to position the graduated nurses in society: 1) mandatory supervision of sanitary visitors by North American public health nurses; and 2) the creation of a nursing school.

Strategy #1: Supervision of Sanitary Visitors and Education of Public Health Nurses

For the first strategy, the house visit service stayed under the control of North American nurses until the first Brazilians graduated and were able to replace them. They were prohibited from working without the supervision of a graduate nurse, and physicians were removed from this activity. To implement this, the Rockefeller Foundation hired, and sent to Brazil, seven other North American public health nurses to assume the roles of professors and supervisors of these visitors in services related to tuberculosis, venereal diseases, and child hygiene.

Another step was to start, for the sanitary visitors already at work, an emergency six-month course. This course was discontinued after the first public health nurses graduated (Moreira, 1921; Sauthier & Barreira, 1999).

Strategy #2: Creating a School for Nurses

The second strategy was to create the DNSP School for Nurses. Clara Louise Kieninger, one of the nurses from the Mission, was invited by Parsons to organize the school and serve as its director. Kieninger had a great deal of hospital experience and was named the Head of Nursing Service at the Assistance Hospital. This hospital was built in front of the place where, in 1927, the School Pavilion would be located.

This public hospital had undergone renovations in the early 1920s, supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. The name was changed to General Hospital Francisco de Assis. The objective of the renovation was to create an outstanding space for the teaching of the medicine schools, and at this point, it also became a field of practice (i.e., clinical site) for the school of nurses. Currently, it is a primary healthcare institution under the scope of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Sousa & Baptista, 1997; Sauthier & Barreira, 1999).

The school of nursing opened in 1923 at the temporary facilities of the Assistance General Hospital. It offered two courses, a Health Visitor course and a Nursing course. The first was a temporary program to train sanitary visitors, noted above in strategy #1, which met the immediate need to bring hygiene and health knowledge to the population. The second, more permanent program, trained professional nurses. (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999).

...the nurses from the Parsons Mission arranged for their students to have a professional experience in appropriate clinical settings, as was typical of leading Anglo-American schools. As they organized the Public Health Nursing Service and the Assistance General Hospital, the nurses from the Parsons Mission arranged for their students to have a professional experience in appropriate clinical settings, as was typical of leading Anglo-American schools. In addition to the Assistance General Hospital, a Sanitary District was organized near the school, making it possible for the students to observe and intervene in areas that affected the population health. Today, students learn to consider not only the health needs of the area, but also how interdisciplinary collaboration can be used to provide integral healthcare to the population (Thornton & Persuad, 2018). This type of collaboration, involving workers from different fields, promotes a different relationship between members of the team, who have mutual and reciprocal responsibilities as opposed to being organized in a traditional vertical hierarchy (Matuda et al., 2015).

Parsons evaluated the work of sanitary visitors, as well as the outcomes they achieved. She viewed their ideal nursing work in public health as a set of educational, preventive, and intervention activities that nurses had the duty to measure and manage. The course offered in the school of nursing prepared these students to be responsible for measuring interventions and results in the fields of health promotion, disease prevention, and relief from suffering (Jones, 2016).

The emergency course started in 1923, and the terms “sanitary visitors” and “nurse visitors” were replaced by “Health Visitors”. This change was to show that the care offered by earlier sanitary visitors, who lacked adequate training, was different than that offered by their replacements, future public health nurses. These nurses would receive their recognition after going through a selective process, and a program of nursing education guided by recognizable criteria based on scientific and professional nursing standards (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999).

The course for health visitors included 15 subjects, seven of which were taught by North American public health nurses. These courses contained theoretical and practical knowledge about procedures of nursing and home hygiene. The course was offered to 44 students, 29 of whom received the Certificate of "Health Visitors" and remained under the supervision of the North American body of nurses.

She viewed their ideal nursing work in public health as a set of educational, preventive, and intervention activities that nurses had the duty to measure and manage. After the 1923 graduation of the first group, the first program evaluation was implemented. Dr. Chagas met with the medical directors of the departments of tuberculosis, child hygiene, and venereal diseases, and they were convinced that, unless the professionals received further training, it would be impossible to improve the public health services. This led to a program revision to offer the health visitors course over 10 months. After completing the 10 month course, students received a certificate that would later allow them to enter a graduation course in the school of nurses. This certificate was proof that they had earned the right to graduate as DNSP nurses, under the direction of the North American professional nurses (Moreira, 1921).

The following class had 34 students. In this class, the health visitors had training in the hospital together with the students of the professional nursing program, in a poor and populous region of an industrial district. This group was trained to deal with the immediate lack of professionals until Graduate Nurses could replace the health visitors. This finally happened in December of 1926. Parsons then discontinued the health visitors’ course, to prevent the creation of another, competing, professional class (Moreira, 1999; Moreira, 1921).

These public health actions were paramount to develop the sanitary reform Chagas needed to implement in Brazil from 1920 to 1924. The economic relevance and growth of Brazilian agricultural products, especially coffee, gained increasing prominence in the post-war period. A healthy workforce was needed, and this encouraged investments in public health, including those in this highly important initiative, the Parsons Mission.

Anglo-American School Elements Adopted in Nursing Education

The DNSP School for Nurses was inaugurated on February 19, 1923, in the pattern of American nursing education. At first it offered the emergency Health Visitor course, but the objective of the school was educating professional nurses to serve in public health (Pava & Neves, 2011).

These public health actions were paramount to develop the sanitary reform Chagas needed to implement in Brazil from 1920 to 1924. In the decade of 1920, the teaching of nursing concepts had already been through many stages of development, disseminated by North American and Canadian nurses who had developed the Standard Curriculum for Nursing Schools in 1917 (Medeiros, Tipple & Munari, 1999). The Parsons Mission brought this curriculum model to the nursing school created in Brazil. Its course was based on the following principles: residence by students at the school; formation in a school created for the purpose and direction by nurses; connection to a hospital in which the nurses would learn nursing practices and be responsible for the assistance offered by the hospital; and rigorous selection of students, who must be females with moral, physical, and intellectual values, in addition to having aptitude for the field (Pires, 1989; Sauthier & Barreira, 1999).

In its basic principles, the 1923 Nursing course was no different from the program instituted in the United States in 1917. It focused on hospital training and attempted to replicate the North American syllabus. The internship was almost entirely in hospitals, including nurses from different specialties, such as surgery, outpatient, maternity, and health center nurses. Nursing in Brazil, which focused on public health in the decades of 1920 and 1930, definitely shifted toward a hospital assistance model in the 1940s (Barreira, 1997; Rizzotto, 2006).

The DNSP School for Nurses was the first nursing school to use the Anglo-American teaching system in the country. The DNSP School for Nurses was the first nursing school to use the Anglo-American teaching system in the country. This was the first time a teaching model was fully implemented, meaning created, developed, and disseminated in Brazilian nursing schools. This implementation was possible only due to the efforts of the Parsons Mission, with support by the Rockefeller Foundation and the Brazilian Federal Government.

The Nursing course lasted for two years and four months and was developed in two stages: Preliminary (elementary teaching) and Professional (hospital and public health teaching) (Peres & Padilha, 2014). Students were supervised by nurses from the Parsons Mission and strictly followed the rules stipulated in a student manual with regard to uniforms, behaviors, and routines. The Parsons Mission conducted ceremonies and rituals in the school which were already present in the North American schools, such as the capping, lamp, and graduation ceremonies, and the nursing oath (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999; Santos & Faria, 2004).

Clara Louise Kieninger, named by Parsons as the first principal of the school, remained in this position from 1923 to 1925. Miss Kieninger graduated from the Lutheran Hospital School of Nursing in St. Louis, Missouri, where she worked as an assistant to the principal for two years before assuming that role herself. She was a part of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I for two years and two months, and taught courses in the field of public health in New York and Canada, and in the field of School Administration at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Miss Kieninger invited her colleague, Anita Lander (Leoward), who came to Brazil in November 1922, to aid her in the task of directing the school by assuming the position of instructor. This position was important and unique, since it required full attention to teaching, unlike that of the other teachers, who also had to work in the hospital (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999). Miss Lander was chosen to be the successor of Miss Kieninger, replacing her in 1926.

This position was important and unique, since it required full attention to teaching, unlike that of the other teachers, who also had to work in the hospital In 1923, the nursing school at the DNSP started work in temporary facilities in the Assistance General Hospital, which was also the setting for theoretical and practical classes of the Faculdade de Medicina do Rio de Janeiro. An important feature of the Anglo-American nursing model was the discipline required from the students in both the classroom and the clinical setting. It assured their moral training and development of the character traits expected of a good nurse, such as sobriety, honesty, loyalty, timeliness, serenity, orderliness, correction, and elegance (Peres & Padilha, 2014). The student living quarters were under the direction of another nurse from the Parsons Mission, who guaranteed that discipline was maintained among students, employees, and professors, each of whom wore different uniforms. These uniforms also worked as disciplinary tools; they signaled in what year of the course the students were enrolled and the norms of behavior according to their place in the nursing hierarchy.

An important feature of the Anglo-American nursing model was the discipline required from the students in both the classroom and the clinical setting. The Parsons Mission established many criteria for admission to the Nursing course. These criteria included: being a single, widowed or legally divorced woman; an age range of 20 to 35 years; having graduated as an elementary teacher or having completed high school; presenting references of good conduct and a certificate from a DNSP doctor attesting good mental and physical health conditions; and absence of contagious diseases or physical defects (Pires, 1989; Sauthier & Barreira, 1999).

Classes were taught by the nurses from the Parsons Mission, by DNSP physicians, and by professors from the school of medicine. In 1923, the Rockefeller Foundation started to build the Pavilion for Nursing School Classes on a piece of land near the Assistance General Hospital. The pavilion was inaugurated in 1927, receiving the formal name of Escola de Enfermagem Anna Nery (Anna Nery Nursing School). The school was named after a Brazilian nurse volunteer who acted with distinction during the Paraguayan War, a conflict which involved Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay from 1864 to 1870 (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999; Cardoso & Miranda, 1999).

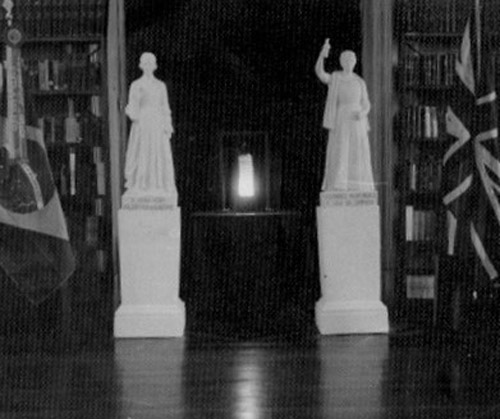

The name Anna Nery was not only paying homage to a war hero, but referred to a Brazilian who worked to build the national identity of the nurses who graduated from the school. One can see, in the photos left by the Parsons Mission, a statue of Florence Nightingale and another of Anna Nery, kept in a room in the nursing school in which ceremonies were held. Picture 1 shows these statues and the flags of Brazil and England, the countries under which these nurses served. Today, they are kept in the Museum of the Anna Nery Nursing School. Initially, they were used during events as way to keep alive, in the collective imaginations of students, the women who influenced the history of nursing in Brazil: Florence Nightingale, as the responsible for the Anglo-American teaching model, and Anna Nery, the national hero who lends her name to the school.

Picture 1. Statues of Anna Nery and Florence Nightingale, with the flags of their countries, inaugurated during the Parsons Mission

Photograph of the Anna Nery School of Nursing Documentation Center, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Brazil (1978b). Academic Acts/Albums and collections. Reproduced with the permission of the Anna Nery Nursing School

... rituals and ceremonies typical of the Anglo-American model of nursing education were brought to the school by the Parsons Mission. As noted above, rituals and ceremonies typical of the Anglo-American model of nursing education were brought to the school by the Parsons Mission. Emblems were also adopted, including the cap, the armband, the brooch, and the flag. Documents kept by the school, such as newspaper clippings, photographs, regiments, and meeting minutes are evidence that these rituals and emblems were essential in the building of a new model of nursing in Brazil. The solemnity with which these were reported show the intention to inspire a professional ideal in the students while motivating feelings such as altruism, patriotism, and humanitarianism. Nurses who received education at this school were prepared to face the world of work in the name of the noblest of causes: the health and well-being of the population (Santos & Faria, 2003).

The uniform also worked as an important element to distinguish the nurses graduated from this school modeled after Anglo-American nursing education. The Maltese Cross was chosen as an insignia for the school and placed in the broches of graduated students and on the flag of the school, which also included an image of a lamp in the middle. In the discourse of a former student who assumed the direction of the school after the Parsons Mission was over, this symbol was noted as significant for the profession because the red Maltese cross drawn in the broch and the armband represented the love for mankind and the privilege that is serving one's neighbors (Sauthier & Barreira, 1999). The uniform also worked as an important element to distinguish the nurses graduated from this school modeled after Anglo-American nursing education. It was worn by all students and professors during institutional activities and help to strategically build the image and the professional identity of nurses in Brazil, visually inserting a new professional in the work market (Peres & Barreira, 2003; Peres & Padilha, 2014).

Picture 2. Symbolic Lamp Ceremony

Photograph of the Anna Nery Nursing School Documentation Center, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Brazil: (1978a). Academic Acts/Albums and collections. Reproduced with the permission of the Anna Nery Nursing School

...health visitors started to be replaced by public health nurses in important activities of the sanitary reform and in Brazilian hospitals. In June 1925, the first class of nurses from the DNSP School of Nurses graduated under the direction of the Parsons Mission. Fifteen students graduated and were called "The Pioneers." The nurses who were exemplary students during the course were offered scholarships from the Rockefeller Foundation for post-graduation studies in universities in the United States. The financial support and awarding of scholarships out of the country, for nurses and physicians, guaranteed that these Brazilian citizens would receive recognition and, as they returned, a position in a public institution (Moreira, 1921; Sauthier & Barreira, 1999). Thus, health visitors started to be replaced by public health nurses in important activities of the sanitary reform and in Brazilian hospitals. This was especially so in the states that needed the most workforce, such as Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, and São Paulo. The creation, in 1926, of the Brazilian Nursing Association gave support to the professionalization of nursing in the Anglo-American Model. In 1931, this association joined the International Council of Nurses. These events elevated the Anna Nery Nursing School as the Brazilian standard for nursing education.

Final Considerations

The social, political, and sanitary context in the capital of Brazil led to reform activities that began in 1920. This reform created the DNSP, and its agreement with the Rockefeller Foundation made viable the Mission of Technical Cooperation for the Development of Nursing in Brazil (Parsons Mission), which lasted from 1921 to 1931. Under the leadership of Ethel Parsons, nurses trained in the United States of America were responsible for professionalizing Brazilian nursing as they developed actions of supervision and formation of nursing personnel.

The first nurse graduates became pioneers who spread through the country to direct health services and schools in other states. Carlos Chagas, a physician reformer and DNSP director, wished to reduce epidemics by using nursing interventions to diminish mortality among the poorest of the population, and guarantee that the workforce was healthy enough for economic growth. For this, Chargas needed to count on public health nurses in sanitary education positions. However, the Parsons Mission exceeded this expectation, creating a nursing school founded upon the highest nursing standards, inaugurating the Anglo-American model of nursing education in the country, and integrating a female profession (at that time) in Brazilian society.

The Parsons Mission remained in Brazil until 1931, and even after this period, the influence of the North American nurses continued with the process of sending Brazilian nurses to seek education in the United States until mid-20th century. The Anna Nery Nursing School was the starting point of a strong nursing curriculum in Brazil, one that is scientific and focused on both theoretical and practical aspects of nursing formation. Under the support of the Rockefeller, foundation, Brazilian health services finally had a professional prepared to work with physicians in the development of new health standards in line with Anglo-American models. The first nurse graduates became pioneers who spread through the country to direct health services and schools in other states. The social and economic development of the country, after the Parsons Mission, could count on the contributions of these professional nurse graduates, who were prepared and committed to act for the good of the population in a variety of situations and settings.

Authors

Angela Aparecida Peters, MS

Email: angelaprodrigues@yahoo.com.br

Angela Aparecida is a PhD student at the Anna Nery School of Nursing / Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (EEAN- UFRJ), and she holds an MS in Nursing from the EEAN-UFRJ. She is a professor of nursing at the College of Medical and Health Sciences - Suprema - Juiz de Fora - Minas Gerais.

Maria Angélica de Almeida Peres, PhD, MS

Email: aguaonda@uol.com.br

Maria Angélica de Almeida Peres is a Nurse Specialist in psychiatric nursing and mental health and is a professor of nursing. She holds an MS and PhD in nursing, with post-doctorate studies in nursing history from Anna Nery School of Nursing / Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Patricia D'Antonio, PhD, RN, FAAN

Email: dantonio@nursing.upenn.edu

Patricia D'Antonio is the Carol E. Ware Professor in Mental Health Nursing and director of the Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia. PA USA

References

Barreira, I. A. (1997). The early days of modern nursing in Brazil. The Anna Nery School Journal of Nursing, 1, 161-176.

Bonini, B., Freitas, G., Fairman, J. & Mecone, M. (2015). American nurses of the special public health service and the human resources training of the Brazilian nursing. Journal of School of Nursing USP, 49(SPE2): 136–43. doi: 10.1590/S0080-623420150000800019.

Brazil. (1931). Decree No. 20.109 of June 15, 1931. It regulates the practice of nursing in Brazil and sets the conditions for teh standardization of nursing schools. Published in the DOU of June 28, 1931, Section I fls 10516

Campos, C., Cohn, A., & Brandão, A. (2016). The Historical trajectory of the health organization in the city of Rio de Janeiro: 1916-2015. One hundred years of innovations and achievements. Science & Collective Health, 21(5). doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015215.00242016.

Cardoso, M. & Miranda, C. (1999). Anna Justina Ferreira Nery: A milestone in the history of Brazilian nursing. Brazilian Journal of Nursing, 52(3). doi: 10.1590/S0034-71671999000300003.

Carrijo, A., Oguisso, T., & Campos, P. (2010). Training and professional practice: Narratives of former students of the School of Nursing Lauriston Job Lane. Care is Paramount Online Research Journal, 2(2), 861-871. Retrieved from: www.redalyc.org/pdf/5057/505750818005.pdf

Castro-Santos, L. A. & Faria, L. R. (2003). Health reform in Brazil: Echoes of the first republic. Bragança Paulista, EDUSF.

Chalhoub, S. (1996). Feverish city: Corticos and epidemics in the imperial court. (pp. 29). Brasil Companhia das Letras.

Faria, L. (2006). Sanitary educators and public health nurses: The construction of professional identities. Pagu Journal, (27): 173-212. doi: 10.1590/S0104-83332006000200008

Jones, T. L. (2016). Outcome measurement in nursing: Imperatives, ideals, history, and challenges. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 21(2). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No02Man01

Lima, N. T., Fonseca, C. M. O., & Hochman, G. (2005). Health in the construction of the National State in Brazil: Health reform in perspective. In N. T. Lima, S. Gerschman, F. C. E., & J. M. Suárez (Eds.), Health and democracy: History and perspectives of the SUS (pp. 27-58). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Fiocruz.

Matuda, C. G., Pinto, N. R. S., Martins, C. L., & Frazão, P. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration in the family health strategy: Implications for the production of care and the management of work. Health & Collective Science, 20(8), 2511-2521. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015208.11652014

Medeiros, M., Tipple, A. C. V. & Munari, D. B. (1999). The expansion of nursing schools in Brazil in the first half of the 20th century. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem, 1(1). Retrieved from: http://www.revistas.ufg.br/index.php/fen/article/view/666/736

Miyamoto, S. (2017). The State of Play: Healthcare Reform in 2017. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 22(2). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol22No02Man01

Mott, M. (1999). Reviewing the history of nursing in São Paulo (1890-1920). Pagu Journal, (13), 327–55. Retrieved from: www.periodicos.sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/cadpagu/article/view/8635331

Moreira, M. (1999). The Rockefeller Foundation and the construction of professional nursing identity in Brazil in the first republic. History, Sciences, Health-Manguinhos, 5(3), 621–645. doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59701999000100005

Moreira, M. (1921). Rockefeller Collection's "Narrative Report of he Service of Nursing/National Department of Health of Brazil/Division of Pubic Heath Nursing.' The Rockefeller Foundation and the construction of a professional identity in nursing during Brazil's first Republic. Casa Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz.

Nursing School Anna Nery. (1978a). Records Center. Digitalized database. EEAN, Class Pavillion, Ceremony for the homage of the Lady with the Lamp during the Nursing Week in 1978. Academic acts collection/2.14.0498.1 front. Description: Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Brazil, 1978

Nursing School Anna Nery. (1978b). Records Center. Digitalized database. Statues of Anna Nery and Florence Nightingale, with the flags of their countries, inaugurated during the Parsons Mission. Academic acts/albums and collections. pg. 6b. Rio de Janeiro: Brazil, 1978.

Pava, A. & Neves, E. (2011). The art of teaching nursing: A history of success. Brazilian Journal of Nursing, 64(1), 145–151. doi: 10.1590/S0034-71672011000100021

Peres, M. & Barreira, I. (2003). Meanings of the uniforms of nurses in the early days of modern nursing. The Anna Nery School Journal of Nursing, 7(1).

Peres, M. & Padilha, M. (2014). Uniform as a sign of an new nursing identity in Brazil (1923-1931). The Anna Nery School Journal of Nursing, 18(1). doi: 10.5935/1414-8145.20140017.

Pires, D. (1989). Hegemonia médica na saúde e a enfermagem: Brasil, 1500 a 1930 Medical hegemony in health and nursing- Brazil: 1500 to 1930. Cortez Editora.

Rizzotto, M. (2006). Historical rescue of the first nursing weeks in Brazil and the national situation. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 59(spe), 423-427. doi: 10.1590/S0034-71672006000700007

Santos, T. (2004). The meaning of emblems and rituals in the formation of the identity of the Brazilian nurse: A reflection after eighty years. The Anna Nery School Journal of Nursing, 8(1), 81–86.

Sauthier, J. & Barreira, I. (1999). North-American nurses and the teaching of nursing in the capital of Brazil: 1921-1931 (A. Nery, Ed.). EEAN/UFRJ.

Souza, C. M. C. (2008). The Spanish Flu epidemic: A challenge to Bahian medicine. History, Sciences, Health-Manguinhos, 15(4), 945–972. doi: 10.1590/S0104-59702008000400004

Souza, M. J. & Baptista, S. S. (1997). Nursing and its practice: The thought and the experienced by the nurses from the São Francisco de Assis Teaching Hospital. The Brazilian Journal of Nursing, 50(3), 345-362. doi: 10.1590/S0034-71671997000300005

Thornton, M. & Persaud, S. (2018). Preparing today’s nurses: Social determinants of health and nursing education. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 23(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No03Man05