Although Florence Nightingale is more famous, Edith Cavell stands out as a nurse who made significant contributions to the nursing profession. She established the first nursing school in Brussels, Belgium. To accomplish this Cavell had to speak fluent French, overcome the disdain of the Catholic Church for replacing their untrained nuns with trained nurses, and establish the importance of her place as a woman in the medical profession. When Belgium was occupied by the German military in World War I, Cavell made a life-or-death decision to defy German laws by joining the Belgian Resistance movement and rescuing Allied soldiers. This article will offer background about Cavell, including Florence Nightingale’s influence on her career. The article presents the significant legacy of this British nurse, and the contributions she made to the nursing profession in her early career and during World War I, the Great War. Her story illustrates both the exemplary nursing leadership and the struggle many nurses experienced when faced with ethical dilemmas in practice. Cavell was a relatively unknown nurse who changed medical and military history. The conclusion considers Cavell’s relevance to nurses of today.

Key Words: Leadership, nursing, ethical decision-making, military history, Belgium, centennial anniversary, war, nurses, wounded soldiers, martyr, The London Hospital, Belgian culture, World War I, German occupation, Nursing Mirror, war injuries.

...Cavell was only forty-nine years old when the Germans executed her for rescuing Allied soldiers in World War I.On May 15, 2019, over a thousand nurses crowded into London’s Westminster Abbey for the annual commemoration of Florence Nightingale’s birthday. But this year was different from the others. This ceremony also honored the centennial anniversary of the return of the body of the martyred British nurse, Edith Cavell. Known as the Florence Nightingale of Belgium, Cavell was only forty-nine years old when the Germans executed her for rescuing Allied soldiers in World War I.

Her body was carried from Belgium to London and honored in a solemn ceremony at Westminster Abbey. More than 250,000 people lined the streets of London to honor her. They stood in silence with their heads bowed and hats off while soldiers carried her coffin. After the ceremony, mourners lined the railway tossing flowers onto the tracks of the train that carried her body up the 115 miles to Norwich, where she was buried. This article will describe who Edith Cavell was, why a century after her death she continues to be honored for her work and sacrifice, how her life was influenced by Florence Nightingale, and how her experience is relevant to modern nursing.

Background

Edith Cavell, was born in December 1865 in the small English farming village of Swardeston (Hoehling, 1958). She grew up listening to her father’s sermons at the small Anglican Church where he was the Vicar. Poor in resources, but rich in warmth and caring, her parents nurtured their children, three girls and one boy. Edith Cavell was the oldest. She grew up learning about truth, dedication, the love of God and humanity. Right and wrong were well defined. Death was interwoven with life and not to be feared. At the time, her parents could never have known that one day their daughter would die for her country and be honored in Westminster Abbey, the most sacred church in all of Britain.

During Cavell’s time, career choices for women were limited to governesses, secretaries, nuns, or nurses.During Cavell’s time, career choices for women were limited to governesses, secretaries, nuns, or nurses. The profession of nursing was slowly evolving. Notes on Nursing, by Florence Nightingale, was first published in 1860, followed the next year by the opening of the Nightingale Home and Training School for Nurses. At first, Cavell had no interest in nursing. She was home-schooled until she reached the age of sixteen and was then sent for further studies to Laurel Court, a school that aimed to give students a rigorous moral training. Discipline was strict. There were no games or physical exercise. French was one of the languages taught to the students, and Cavell showed a flair for it. When she graduated, the school matron found a position for her as a governess with a French-speaking family in Brussels, Belgium (Evans, 2008).

Cavell loved Brussels. She found it a vibrant city that pulsed with culture, beauty, music and activity. Five years later, when her father became critically ill, she returned home. Edith was thirty years old when she stood at her father’s grave in the little church cemetery and promised him she had found her calling. She would become a nurse (Brown, 2007).

In 1896, Cavell sat for her interview to be accepted into the nursing school at The London Hospital in the East End of London. Eva Luckes, the Matron of the school, diligently worked to overcome the public’s perception that nurses were like the Charles Dickens’ character Mrs. Gump, who was a repugnant domestic servant, working with a dust rag in one hand and a bottle of booze in the other (Judson, 1941). Miss Luckes modeled her curriculum after that of the first school founded by Miss Nightingale at the St. Thomas Hospital.

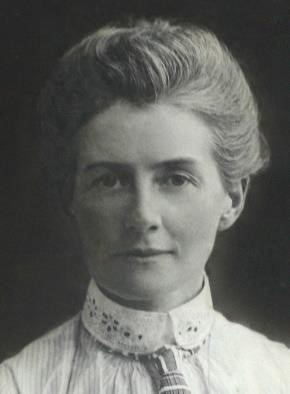

Picture 1. Edith Cavell, around aged 30 (Public domain).

When Cavell entered Miss Luckes’ office for her interview, the first thing she saw was a sign on the wall that read “Patients Come First.”Luckes challenged the board of directors at The London, as it was called then, to provide her with the finances to build a nursing school of which the hospital could be proud. On the merits of her arguments, she was given the budget she needed. She endeavored to adhere to the principles of nursing set out by Miss Nightingale. Aside from her business-like manner, however, she had a heart of empathy and kindness for her nurses and patients (McEwan, 1958). When Cavell entered Miss Luckes’ office for her interview, the first thing she saw was a sign on the wall that read “Patients Come First” (Collins, 1995, p.18).

At the time, both Luckes and Florence Nightingale strongly disapproved of the registration of nurses. Miss Nightingale stated that registration would “stereotype mediocrity” (McEwan, 1958). Miss Luckes believed it would stifle a “healthy rivalry” among the hospital training schools (p. 27). It was not until 1909, at the second Quinquennial Congress of the International Congress of Nurses in London, that despite the opposition of 232 hospital matrons for the petition for statutory registration, it was successfully passed (Evans, 2008).

She wanted to do whatever she could for those who were helpless, hurt, and in need of medical care.Cavell could have chosen any school that trained nurses, but she selected this one because it was in Whitechapel, a poor section of London. She wanted to do whatever she could for those who were helpless, hurt, and in need of medical care. On one occasion, during her training in the maternity ward, she was helping with a delivery when the mother tearfully told her that the baby should have died because she could not afford to feed it. Cavell asked Miss Luckes if she could find a job for the mother at the hospital and said she was willing to donate a part of her nurse’s salary to help support the indigent mother and child. Miss Luckes was reluctant, but Cavell persisted. Miss Luckes finally agreed to find a place for the mother, but she also admonished Cavell about her tendency to get over-involved with patients and become emotionally attached to them. Unbeknownst to both of them, these words foreshadowed later events in Cavell’s life (Ryder, 1975).

Picture 2. Eva Luckes, Matron of the London Hospital School of Nursing from 1880 to 1919. (Public domain).

Florence Nightingale’s Influence

Cavell idolized Florence Nightingale and vowed that she would follow her example and devote her life to the sick.Cavell idolized Florence Nightingale and vowed that she would follow her example and devote her life to the sick. When asked if she would like to marry, Cavell responded that she had chosen to follow Miss Nightingale’s example and reject personal gratification. She explained that she was married to her work (Judson, 1941).

Early Career

She simply saw it as an opportunity to make a difference in nursing and accepted Dr. DePage’s offer.Following graduation, Cavell held various nursing positions. She worked her way up to hospital nursing supervisor and then instructor at a nursing school. It was a position she loved, but after she returned from a vacation, her teaching position was reassigned. While working in a temporary position in Manchester, England, she received a letter from Dr. Antoine DePage, a surgeon in Belgium. Dismayed by results of the poor care untrained nuns were providing to his patients, he was searching for a way to train his own nurses. He wanted the nursing students to be taught like they were at Florence Nightingale’s school in London. His wife, Marie DePage, had kept in touch with the Francois family, for whom Cavell had once been a governess. Marie suggested to her husband that he write to Cavell to come to Brussels and establish the first nursing school in Belgium. When Cavell received the invitation, she did not realize the magnitude of such an undertaking. She simply saw it as an opportunity to make a difference in nursing and accepted Dr. DePage’s offer. (Hoehling, 1958; Judson, 1941; Souhami, 2010).

The Work in Belgium Begins

In addition to overseeing repairs, she also had to write the curriculum; design the uniforms and have them made; and find trained instructors.When she arrived, Cavell was shocked at the sight of the four side-by-side buildings where she was to create a nursing school, living quarters, a laboratory, and a classroom. They were dilapidated and finances for repairs were meager. Worse yet, the first students were scheduled to arrive in four weeks. In addition to overseeing repairs, she also had to write the curriculum; design the uniforms and have them made; and find trained instructors. She appealed to Marie DePage for help. Standing in what would be her future office, she picked up a fallen chair, brushed the dust off the wobbly desk, sat down and wrote to Miss Luckes asking for help to find French-speaking nursing instructors. One nurse she hired was Elizabeth Wilkins, a Welsh nurse, who became a close friend and confidante (Ryder, 1975). Cavell’s nursing school, called L'École Belge d'Infirmières Diplômées, was established in 1907 (Judson, 1941). Students worked at the public hospital called the Berkendael Medical Institute.

In Belgium, a woman who tended to patients in a hospital lost her status in society.But the problems did not end there. Finding female recruits was difficult. In Belgium, a woman who tended to patients in a hospital lost her status in society (Upjohn, 2000). This was why nuns had been providing bedside care. Only one of the five students who enrolled in Cavell’s school was Belgian. In addition, Belgium was a Roman Catholic country, and the church bristled at having a British Anglican training their women to replace their nuns (Evans, 2008). The Mother Superior had control over nursing care in Belgian hospitals. It was a powerful position, and she detested the competition. She asked the bishop to publish a rebuke of Cavell and her school in the newspaper. The bishop complied with her wishes.

Cavell also discovered that working with Dr. DePage created another challenge. Although this surgeon was known to be the most skilled in Belgium, he was not known for his pleasant temperament. Disagreements between the hot-headed surgeon and his strict new matron were frequent. One dispute concerned his dismissal of one of her students for not wearing a starched collar on her uniform. Cavell told him he had no right to discharge the student without first discussing it with her. The ensuing disagreement established who was really in charge of the nursing school, and it was not Dr. DePage (Richardson, 1985). He also hated Cavell’s dog, Jack. When he demanded she get rid of Jack, Cavell, who loved all animals, threatened to leave. It was Marie DePage who was able to negotiate a truce between her husband and Cavell to save the school.

Nursing School Flourishes

The term “professional” began to be applied to nurses.Cavell struggled with under-enrollment for seven years, until one unforeseen incident solved the problem. The Belgian Queen Elizabeth broke her wrist and refused to go to St. Jean’s, the traditional Roman Catholic hospital. She demanded to be taken to the hospital with trained nurses. Following that incident, the school’s enrollment soared. By 1914, Cavell was responsible for managing nursing students in three hospitals, three private nursing homes, twenty-four communal schools, thirteen private kindergartens, a clinic, and private-duty cases. Entering a man’s world, she gave four lectures a week to physicians and nurses as an expert and equal (Brown, 2007). In addition, Cavell created a new career path for women in Belgium, elevating their status. The term “professional” began to be applied to nurses. Her school became internationally famous, and attracted students from all over the world. A new school had to be built to accommodate the influx of new students.

Picture 3. First students in Edith Cavell’s nursing school in Belgium, 1907. (Public domain).

World War I: The Great War

While Cavell was visiting with her mother in Norwich in 1914, World War I was declared. In August, thousands of German soldiers marched into neutral Belgium with the goal of conquering France. England was an ally of France and Belgium, and entered the war to protect them. Against the pleading protests of her mother, Cavell responded, “My place is in Brussels. It is my duty to return to the school” (Judson, 1941, p. 171). Back in Belgium, she discovered that nothing was the same. Almost all of her nurses had fled the country.

The Germans were brutal occupiers. For no reason they arrested citizens, shot them, or forced them to work in their munitions factories. They posted signs all over Belgium warning that anyone who hides the enemy would be severely punished (Horne & Kramer, 2001).

Cavell took the nurses aside and told them they must do their duty for everybody who needed their help.Germany set up a military administration to govern the Belgian civilian population. One of their first acts was to take over the country’s hospitals. After Cavell’s school was closed, she and Nurse Wilkins joined the German ranks of nurses and doctors who worked in the Red Cross hospitals. Cavell’s nurses detested caring for German soldiers. Some soldiers kept their guns in their beds and threatened to shoot the nurses if they did not comply with their demands. Cavell took the nurses aside and told them they must do their duty for everybody who needed their help. Cavell believed in the humanity of all people. She admonished her nurses to rise above their prejudices and treat whomever God put in their care. She did not discriminate on the basis of nationality, race, religion, or country (Judson, 1941).

Caring for Wounded and Enemy Soldiers

She became known as the poor man’s Nightingale.Soldiers were carried in with war injuries she had never seen before. The men suffered from trench foot, severe shell shock, missing limbs, bubonic plague, shrapnel wounds, and the devastating effects of chlorine and mustard gas. Cavell kept a diary or register of many soldiers she cared for (Ryder, 1975). Her nursing skills were not limited to working in the hospital. In the evening she went out into the streets and cared for the sick and injured. She became known as the poor man’s Nightingale.

For eight years, she submitted articles to the Nursing Mirror, a popular nursing magazine (Nursing mirror, 1914) During the war her role shifted and she served as their official war correspondent. She felt it was important for the nursing community to know the circumstances in Belgium. Below is an example of one of her communications:

21 August, 1914

To the Nursing Mirror,

There were at least 20,000 soldiers who entered the city….We prepared 18,000 beds for the wounded; all sorts and conditions of people were offering to help, giving mattresses and blankets, rolling bandages, and making shirts. Our chief thought was how to care for those who were sacrificing so much and facing death…Homes have been burnt and battered, villages razed to the ground, women and children murdered, drunken soldiers raping, looting and mutilation….We have been cut off from the world” (Cavill, n.d.).

On the night of September 14, 1914, two wounded British soldiers knocked on the door of her clinic to seek help. Cavell had seen the signs warning that anyone who took in an enemy soldier would be put to death. As she stood in the doorway staring at the tortured faces of the two soldiers, who could barely stand, she had a difficult decision to make. Should she obey the law and refuse them, knowing they would suffer from their wounds or be executed, or should she have the courage to face the possibility of her own demise and put the safety of these soldiers first? She opened her door and welcomed them (Upjohn, 2000). A member of the Belgian Underground then approached Edith to ask if she would be willing to work with them to rescue Allied soldiers. They would assign the soldiers to guides who could move them to the neutral country of the Netherlands.

She felt it was important for the nursing community to know the circumstances in Belgium.Ethical Dilemma of Working with the Underground

Cavell was now forty-eight years old. As the daughter of an Anglican minister, she had never before done anything subversive. She knew that assisting Allied soldiers to escape Belgium meant disobeying German law. But was not God’s law more important than theirs, she reasoned? Were not thousands of soldiers dying in the trenches every day, sacrificing their lives for what was right? Was it not right to fight tyranny by saving the lives of good people? In nine months, she became the key link in the Underground movement of Belgium. The Germans could not understand how the Belgian Resistance was so successful.

Picture 4. Edith Cavell and Her Beloved Dogs, Don and Jack. (Public domain).

Arrested for Treason

But turning these soldiers away was contrary to Cavell’s strong duty-bound nature.As time went on, Nurse Wilkins warned Cavell to stop taking in wounded soldiers because the Germans were becoming suspicious of her activities. But turning these soldiers away was contrary to Cavell’s strong duty-bound nature. Then, the inevitable happened. A British soldier wrote a note to Cavell thanking her for saving his life. During a raid on her clinic, a German officer found the note and arrested her for treason (Hoehling, 1958). At the same time, a Belgian spy working for the Germans revealed the entire operation to them.

Cavell was placed in solitary confinement at St. Giles Prison. Over the ten weeks she was held prisoner, Brand Whitlock, who held the duel responsibilities of Ambassador for both the Americans and the British, tried to have his lawyer defend Cavell. But neither he nor any other lawyer was allowed to prepare a case for her defense. Unable to lie even when her life was a stake, Cavell admitted to helping over two hundred soldiers escape. However, in Edith Cavell, Roland Ryder wrote that after interviewing many of the men Cavell rescued, he believed the number may have been closer to a thousand. (Ryder, 1975).

Unable to lie even when her life was a stake, Cavell admitted to helping over two hundred soldiers escape.The Germans drew up a confession, written in German, for her to sign. Although German was a language she did not understand, she signed it (Brown, 2007). This confession was used to find her guilty of treason for which the punishment, under German military code, was death.

Consulates from Spain, Belgium, America, and England made desperate pleas to save her life. Secretly, they thought the threat of execution was a ruse and that Cavell would be spared, but they were wrong. The Germans wanted to send a strong message to the Allies of the consequences of breaking their laws. In a three-minute trial, the Germans found Cavell guilty and sentenced her to be executed by a firing squad at sunrise the next morning. They hoped this timing would prevent anyone from interceding on her behalf. That night the only Anglican priest in Brussels was allowed to visit. He found her calm and willing to sacrifice her life for those she rescued (Ryder, 1975).

“Standing as I do in view of God and eternity, I realize that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness toward anyone,” Cavell told him (Ryder, 1975, p. 214). At Cavell’s request, together they sang the hymn “Abide with Me.”

Execution

On the morning of May 12, 1915, Edith Cavell and Philippe Baucq, the head of the Underground, were brought ten miles north of Brussels to the Tir National Firing Range in Schaerbeek. Baucq was shot first. Cavell’s gray eyes blazed with courage as she stood before the line of eight riflemen who would soon end her life. The physician who declared her dead found only four bullet holes in her body; four of the German soldiers had deliberately shot wide. She was buried where she lay, with a simple wooden cross marking her grave.

Picture 5. Execution of Edith Cavell.

The commanding officer fired the final shot. (Public domain).

Death may have snuffed out her life but her murder ignited the world.Death may have snuffed out her life but her murder ignited the world. The Germans soon learned that executing Cavell was the worst mistake they had made in this war. Her death was heralded in frontline news all over the world. The German’s purpose in killing a beloved British nurse had been to devastate the morale of the British army so they would pull out of the war, but they misjudged the fortitude of the British. This barbaric act created a worldwide shock. Revulsion, indignation and outrage spurred thousands of British men to line up at the recruitment offices to avenge her death (Ryder, 1975). Australians and Canadians also responded. Up to this time, America had resisted to joining the war in Europe, but this outrage changed the attitude of the American public and on April 6, 1917, American soldiers joined the Allied forces and helped defeat the Germans.

The war was over November 11, 1918. In May 1919, Cavell’s body was disinterred and brought home to England. She was honored at Westminster Abbey and then brought to Norwich where some of the pallbearers where the same soldiers she had rescued (Ryder, 1975; Upjohn, 2000). Pictures 6 and 7 show this return to England.

Picture 6. Cortege Honors Edith Cavell at Westminster Abbey, May 1919. (Public domain).

Picture 7. Edith Cavell’s Body Arrives from London.

Her body is transported to the Norwich Cathedral. The pallbearers are soldiers she rescued. (Public domain).

Every October, a memorial service is held in Norwich in her honor. Her favorite hymn, “Abide with Me,” is sung as a reminder that she was the “help of the helpless,” as mentioned in the hymn (Hoehling, 1958).

Conclusion: Cavell’s Relevancy to Nurses of Today

Edith Cavell is memorialized throughout the world.Edith Cavell is memorialized throughout the world. Over one hundred memorials have been erected in fifteen countries including the United States. Several books have been published about her life: Arthur (2014a, 2014b), Boston (n.d.), Clark-Kennedy (1961), Van Til (1922), and Whitlock (1919), among many others. A forty-five foot statue in her image (see picture 8) was erected near Trafalgar Square and another outside Norwich Cathedral.

Picture 8. Forty-Five Statue Honoring Edith Cavell near Trafalgar Square (Author, personal collection).

She thought of herself as “just a nurse who did her duty.”Canada named a mountain after her. Cavell would have been humbled by all of this. She thought of herself as “just a nurse who did her duty” (Souhami, 2010, p. 375). She was the ultimate advocate for nurses and their patients. The Vicar of the Norwich Cathedral said her death was not a tragedy but a triumph. “She died forward,” he said during the ninetieth memorial ceremony honoring her life (Vicar of Norwich Cathedral, 2005 audio).

On May 15, 2019, I stood in Westminster Abbey with a thousand of my nurse colleagues to honor two of history’s greatest and most influential nurses. The pamphlet for the service read:

“We give thanks for the life and work of Florence Nightingale and Edith Cavell, and for those whom they have inspired to serve with care and compassion” (Florence Nightingale Foundation, Cavell Nurses Trust, 2019, p. 13).

“She (Cavell) remains and inspiration to many, and we are proud and privileged to maintain Edith Cavell’s legacy in our work today.” (p.3).

Nurses today risk their lives to care for patients...Since my books on Edith Cavell were published, hundreds of nurses have written to me reflecting on how this story has touched their lives, reminded them of what nursing is fundamentally all about, and inspired them anew in the practice of their profession. The story of Edith Cavell’s life raises two issues. To what extent should a nurse put her own life in jeopardy for her patients, and under what circumstances would it be right for a nurse to defy civil and military authorities or engage in subversive activities? Nurses past and present have struggled with the answers to these moral questions. Nurses today risk their lives to care for patients, prompting this refrain, Save one life and you’re a hero. Save a hundred lives and you’re a nurse (author unknown).

Authors

Terri Arthur, BS, MS, RN

Email: tarthur1@capecod.net

Terri Arthur is the first nurse to write about the heroic British nurse Edith Cavell. After six years of research which took her to Belgium and the United Kingdom, she was inspired to pen the moving story into the award winning historical novels, "Fatal Decision: Edith Cavell WWI Nurse" (Second Edition - American version), “Fatal Destiny: Edith Cavell WWI Nurse” (British Edition), “Edith Cavell: Nurse Hero” (Children’s edition ages 8-11). Arthur has worked as a critical care nurse, staff educator, and clinical manager. She is the founder and director of a continuing education company, Medical Education Systems, a business that provides continuing education to nurses, doctors, and medical personnel. She is a charter member of the Nightingale Society of the Massachusetts Nurses Association in recognition for her generous support for nursing scholarship and research. Arthur is the first and only American to have been invited to participate in the memorial ceremonies for Edith Cavell in both Norwich and London. Further information about her interviews, articles, and public appearances can be found on her website www.fataldecision-edithcavell.com.

References

Arthur, T. J. (2014a). 1912 Fatal decision: Edith Cavell WWI Nurse (2nd ed.). HenschelHaus Publishing.

Arthur, T. J. (2014b). 1914 Fatal destiny: Edith Cavell WWI Nurse [British Edition]. HenschelHaus Publishing.

Boston, N. (n.d.) The dutiful Edith Cavell. Norwich Cathedral.

Brown, G. (2007). Courage: Eight portraits. Bloomsbury.

Cavill, E. (n.d.). Letters. Imperial War Museum, London, UK.

Clark-Kennedy, A.E. (1961). Edith Cavell: Pioneer and patriot. Farber and Farber.

Collins, S. M. (1995) The Royal London Hospital: A brief history. The Royal London Hospital Archives and Museum.

Evans, J. (2008). Edith Cavell. The Royal London Hospital Museum.

Florence Nightingale Foundation, Cavell Nurses Trust. (2019). 2019 Florence Nightingale Commemoration Service program. Westminster Abbey.

Hoehling, A. A. (1958). Edith Cavell. Cassell.

Horne, J., & Kramer, A. (2001). German atrocities 1914: A history of denial. Yale University Press.

Judson, H. (1941). Edith Cavell. Macmillan.

McEwan, M. (1958). Eva C. E. Luckes, Matron, the London Hospital, 1880-1919. London Hospital League of Nurses.

Nightingale, F. (1860). Notes on nursing: What it is, and what it is not. D. Appleton.

Nursing Mirror. (1914, August 21). Royal College of Nursing Archives, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Richardson, N. (1985). Edith Cavell. Hamish Hamilton.

Ryder, R. (1975). Edith Cavell. Hamish Hamilton.

Souhami, D. (2010) Edith Cavell. Quercus.

Upjohn, S. (2000). Edith Cavell: The story of a Norfolk nurse. Norwich Cathedral.

Van Til, J. (1922). With Edith Cavell in Belgium. H. W. Bridges

Vicar of Norwich Cathedral. (2005). Eulogy [Audiotape recording]. T. Arthur.

Whitlock, B. (1919). Belgium: A personal narrative. D. Appleton.