War and human conflict have historically propelled the profession of nursing forward, due to the intense demand for large numbers of efficient, high-quality nurses to care for injured troops. This article begins with an overview of nursing in the United States Army and Navy Nurse Corps and the influences of war on the advancement of American nursing, with a specific focus on the Army School of Nursing. As a response to the need for nurses in World War I, the Army School of Nursing was a novel approach to educating new nurses to be quickly mobilized in wartime and to provide nursing care at base hospitals across the United States. Students provided care to thousands of troops during the influenza pandemic of 1918, and several lost their lives providing care at these military encampments, including Fort Riley, the suspected starting point of the influenza epidemic in the United States.

Key Words: Nursing history, Army nursing, Navy nursing, nursing education, influenza, World War I

Crises often challenge nurses to practice at the fullest extent of their training, and to develop novel ways to train large numbers of nurses to provide care in difficult settings.Advances in nursing and medicine often arise to meet the needs of humanity in times of crises, including disasters, wars, and epidemics. These catastrophic events propel nursing knowledge, practice, and education forward, and ultimately lead to improvements in care. Crises often challenge nurses to practice at the fullest extent of their training, and to develop novel ways to train large numbers of nurses to provide care in difficult settings. This is especially true for nurses serving in the military.

Using traditional historical methods with a social history framework, I explored the influences of war on the advancement of American nursing, with a specific focus on the Army School of Nursing as a case study. The Army School of Nursing was a novel approach to nurse education through the use of a national, standardized curriculum, as well as acquainting student nurses with military hospital culture and practices. The Army School of Nursing laid the groundwork for future military recruiting efforts for nurses, including the Nurse Cadet Corps used during World War II to recruit student nurses for future military service.

The Army School of Nursing was a novel approach to nurse education through the use of a national, standardized curriculum...A social history framework was used herein to highlight “the experiences, behavior, and agency of those at societies margins, rather than on its elite.” (Connolly, 2004, p. 5). In this case, rather than focusing on the dean of the Army School of Nursing or commanding officers of the base hospital, the focus is on the students, and how these greater social, political, and environmental forces influence their actions and experiences. Primary source material related to the Army School of Nursing was accessed from the National Archives in College Park, MD and the Midwest Nursing History Research Center in Chicago, IL. Secondary source material included, A History of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps by Mary Sarnecky (1999), In and Out of Harm’s Way: A History of the Navy Nurse Corps by Doris Sterner (1996), and The Lamp and the Caduceus: The Story of the Army School of Nursing by Marlette Condé (1975).

Nursing in the U.S. Army and Navy

Although the birth of professional nursing is generally attributed to Florence Nightingale and her work in the Crimean War in the 1850s, family members, Catholic nuns, and volunteers have been caring for the sick and wounded for far longer. From the American Revolutionary War through the Civil War, nursing care in the United States (U.S.) military was provided by soldiers and stewards, or local community members housing the wounded in their homes. Starting in 1856, Congress passed legislation allowing the enlistment of hospital stewards, and in 1861, untrained civilian nurses were contracted by the Army to provide nursing care to soldiers (Sarnecky, 1999).

...in 1861, untrained civilian nurses were contracted by the Army to provide nursing care to soldiers.During the Civil War, the first designated Naval Hospital ship, the Red Rover made its way up and down the Mississippi River providing care to almost 3,000 patients between 1862 and 1865. Aboard this ship were three Catholic nuns; the first trained nurses used in the Navy, as well as five untrained Black nurses working under the direction of the sisters (Sterner, 1996). The quality and efficiency of the trained nurse as part of the military was a powerful argument for the inclusion of women. The Civil War also afforded the opportunity for Black women to enter historically White spaces, such as the U.S. Navy, and provide care regardless of race.

The quality and efficiency of the trained nurse as part of the military was a powerful argument for the inclusion of women.The Civil War also prompted the reappearance of general hospitals to supplement the tented field hospitals, with almost 200 general hospitals in operation by the mid-1860s in the Union alone (Sarnecky, 1999). Evidence from both Florence Nightingale in the Crimean war and the American Civil War supported the idea that positive patient outcomes were correlated with the diligence and training level of the nurse, leading to the development of several hospital-based training programs (Sarnecky, 1999). The expansion of hospitals and data supporting the use of trained nurses was a catalyst for professional nurse training programs in the United States. After the end of the Civil War in 1869, the American Medical Association formally recognized the need for trained nurses in hospitals, further legitimizing nursing as a profession (Sterner, 1996).

The highly successful and integral role of the nurse during the Spanish-American War convinced even more medical officers of the necessity of trained nurses during wartime, further elevating the profession of nursing.At the turn of the twentieth century the United States engaged in another conflict: The Spanish-American War. This war created new challenges for the Army Medical Department, where the most dangerous enemy was not the Spanish, but disease. Soldiers suffered greatly from typhoid, yellow fever, infectious diarrhea, and malaria, due to tropical weather conditions and poor sanitation. However, the Army was still reluctant to contract trained nurses, as women were excluded from military spaces. Initially, the Army relied on the Army Hospital Corps to nurse the sick, which consisted of untrained, enlisted corpsmen. When this approach proved inadequate to meet the medical needs of the soldiers, trained nurses were reluctantly contracted to care for the soldiers in base hospitals, and again proved their worth through their quality work (Sarnecky, 1999).

Navy nurses, both trained and untrained, served during the Spanish-American War in Cuba, the Philippines, New York, and Virginia. The first hospital ship to fly the Geneva Red Cross flag, the USS Solace, staffed eight trained nurses and was used to ferry soldiers from Cuba back to Naval hospitals in New York, Virginia, and Boston (Sterner, 1996). The highly successful and integral role of the nurse during the Spanish-American War convinced even more medical officers of the necessity of trained nurses during wartime, further elevating the profession of nursing.

The Beginnings of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps

Due to their success in the Spanish-American War...nurses began to advocate for official integration, first into the Army, followed by the Navy.By 1900, nursing was recognized as a respected profession with the publication of the American Journal of Nursing, and over 500 hospital-based nursing programs had graduated approximately 10,000 trained nurses (Sterner, 1996). Due to their success in the Spanish-American War and their firm position as an essential part of the medical department in the Army and Navy, nurses began to advocate for official integration, first into the Army, followed by the Navy. The Committee to Secure by Act of Congress the Employment of Graduate Women Nurses in the Hospital Service of the United States Army was formed in 1899, and in two years they officially succeeded in creating the Army Nurse Corps as part of the Army Reorganization Act on February 2, 1901 (Sarnecky, 1999). After two failed attempts to establish the Navy Nurse Corps in 1902 and 1904, the bill finally passed on February 6th, 1908, seven years after the establishment of the Army Nurse Corps. As the first women to be part of the U.S. military, both Army and Navy nurses existed in an undefined space within the military ranks. Nurses had no rank as military officers, but were also not considered enlisted. This ambiguity of authority and power sometimes made it difficult for nurses to assert themselves within the military hospital structure (Sterner, 1996).

Nurses had no rank as military officers, but were also not considered enlisted.A total of twenty nurses formed the inaugural class of the Navy Nurse Corps with one superintendent, two chief nurses, and seventeen nurses. New Navy nurses reported to Washington for a six-month orientation to the Navy, and were then sent across the mainland and abroad to naval hospitals. Upon arrival, these new Navy nurses were assigned to their duty stations and trained on the ward with a senior nurse for several weeks. Navy nurses were committed to properly training the corpsmen in all aspects of bedside nursing care including baths, treatments, and medication administration. The Navy was sure to recruit nurses who would not only be good at the bedside, but would also be good instructors.

After the enlisted men were trained, the men were often reassigned to Navy ships or Marine units as the only person with any nursing knowledge. They would be responsible for the care of any ill or injured sailors until they could reach a medical facility (Sterner, 1996). These Navy nurses showed their value as educators as well as care providers by teaching the men the essentials of nursing, which would become invaluable aboard a battleship. Navy nurses were also leaders, responsible for supervising and delegating tasks to the male corpsmen, placing women in an unofficial position of authority over men within the rigid military structure.

The Navy was sure to recruit nurses who would not only be good at the bedside, but would also be good instructors.The Army Nurse Corps initially consisted of the 202 contract nurses who elected to stay with the Army following the end of the Spanish-American War. However, these numbers dropped dramatically in peacetime, with the original 202 members dropping to 99 nurses by 1903. Poor rations, difficult work environments, and ineffective leadership contributed to the decrease in the Army Nurse Corps numbers. In 1909 under new leadership, the Army Nurse Corps again began to make improvements through expanding food allowances, improving staffing, shortening shifts, and improving the nurses’ living quarters (Sarnecky, 1999).

The Need for Nurses in World War I

Navy nurses were also leaders...placing women in an unofficial position of authority over men within the rigid military structure.As tensions mounted in Europe, the United States began to aggressively recruit American nurses in case they might be needed to serve their country as part of another war. By 1912, over 3,000 nurses had been recruited for the Army Nurse Corps reserve through a partnership with the American Red Cross, and there were 125 active duty nurses in the Army Nurse Corps (Sarnecky, 1999). The Navy Nurse Corps continued to grow as well, nearly doubling in number by 1909, and increasing to 190 active nurses, with an additional 155 from reserve to active duty by July 1917 (Sterner, 1996).

This recruiting model was able to produce a large number of professional nurses ready to mobilize quickly; however...there was often a steep learning curve when providing care.In 1914, World War I broke out in Europe with a ferocity that had yet to be seen. Although the United States avoided engaging in the Great War for the majority of the conflict, the Army Department of Medical Relief, the Army Nurse Corps, and the American Red Cross prepared and coordinated their plans to care for those wounded, organizing and mobilizing fifty base hospitals, and drawing resources from the staffs of large civilian hospitals. The Red Cross and Army agreed that if the United States officially entered the war, all hospitals would become actual Army units, and the Red Cross Volunteer nurses would automatically be inducted into the Army Nurses Corps (Sarnecky, 1999). This recruiting model was able to produce a large number of professional nurses ready to mobilize quickly; however, as they usually had no experience with military nursing, there was often a steep learning curve when providing care within the rigid structure of the Army. Additionally, American nurses often worked alongside professional nurses from Europe, who also approached their work differently than their American counterparts.

Nurses also provided care to victims of poisonous gases...many learning on the job about these unique casualties.Once the United States officially entered World War I on April 6, 1917, military nurses continued to witness the horrific casualties of war, compounded by debilitating effects of mustard gas and the pandemic flu (Sterner, 1996). Thousands of nurses provided care to patients throughout Europe, and cared for battle casualties using intense irrigation and debridement as the primary method to prevent infection. Nurses also provided care to victims of poisonous gases, in specialized units, and in overcrowded and understaffed evacuation hospitals, with many learning on the job about these unique casualties. Outside of Europe, other American nurses served throughout the world in the Territory of Hawaii, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, on transatlantic transport ships, and domestically at Army hospitals across the United States (Sarnecky, 1999). As the war continued to intensify, it became clear that there was still a shortage of trained nurses to meet the needs of an ongoing war in Europe, as well as care for troops and civilians at home.

The Beginnings of the Army School of Nursing

The idea was that student nurses would provide care on domestic military bases under the supervision of Army nurses and school faculty.The Army School of Nursing was first conceived on June 4, 1917 as a response to the U.S. involvement in World War I, in order to meet the demand for trained nurses in both civilian and military capacities (Condé, 1975). The idea was that student nurses would provide care on domestic military bases under the supervision of Army nurses and school faculty. As military bases were becoming crowded with soldiers awaiting deployment abroad, the school seemed an elegant solution to both the shortage of nurses on bases as well as the lack of military knowledge found in most of the reserve nurses serving during World War I.

The Nursing Committee of the General Medical Board of the Council of National Defense, consisting of medical and nursing leaders from the Army Nurse Corps, Navy Nurse Corps, Red Cross, Public Health Service, American Medical Association, American Nurses Association (ANA), and American Hospital Association, discussed how best to meet the needs anticipated for the war effort. Annie Goodrich, ANA president, advocated for using supervised student nurses trained in military hospitals; however she was unsuccessful in convincing her fellow committee members. Instead, the committee responded by requesting improved living conditions and staffing of military hospitals, as well as a detailed inspection of the nursing care and conditions in military hospitals. These inspections revealed a concerning disparity in nursing care at military hospitals compared to similar civilian institutions due to a lack of uniformity among units and poor training of corpsmen (Condé, 1975).

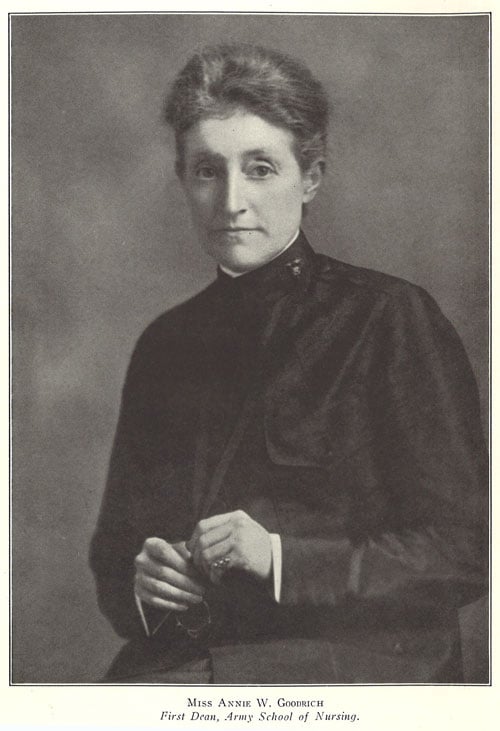

Armed with convincing data from the inspections, Goodrich was successful in persuading the committee to authorize the school...On March 14, 1918, the findings of the inspections were reported to the Nursing Committee, and again Annie Goodrich brought up the idea of the Army School of Nursing (Photo 1). Armed with convincing data from the inspections, Goodrich was successful in persuading the committee to authorize the school on May 25, 1918. Plans developed quickly, and by July 1918, over 4,000 students had applied and been accepted. The first unit opened on July 25, 1918 at Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Other units quickly followed, and by November 1918, over 5,000 applicants had been accepted, and 1,099 were on duty at twenty-five military hospitals across the United States (Condé, 1975). Although the nurses cared for encamped soldiers and lived on base, they maintained civilian status and were under no obligation to join the Army Nurse Corps upon graduation (Sarnecky, 1999).

Photo 1: Annie Goodrich, Dean and Founder of the Army School of Nursing, as published in The Annual (1921).

Midwest Nursing History Research Center, University of Illinois Chicago College of Nursing (Used with permission)

Thousands of Americans felt compelled to serve...Due to the tremendous need for nurses on the U.S. military bases and abroad, it was imperative that the school be functioning as soon as possible and accept as many qualified applicants as possible. At the time, advertisements and pleas for men and women to serve their country were inescapable. Thousands of Americans felt compelled to serve, including women from different classes and educational backgrounds; however, opportunities for service remained restricted to white men and women. Due to the nationalistic pride experienced by many women, applicants for the brand new Army School of Nursing came from newly graduated high school students, college students, as well as established professionals, from across the country, creating a cadre of nursing students unlike any other in the United States. Army School of Nursing Student Gilberta Durland describes the phenomenon in the 1921 Army School of Nursing yearbook:

In the memorable fall of 1918 there gathered from far and near a motley assortment of girls, just plain girls one would have called us, but no, we were teachers, business girls, college girls, music students, girls from every walk of life, all responding to the same appeal, all cheerfully laying aside our former hopes and ambitions to answer our country’s cry for help (Durland, 1921, p. 215).

November 11, 1918, marked the end of World War I and the fighting abroad. However, following Armistice Day, nurses around the world were called to serve against another serious threat to the health and safety of their communities: the influenza pandemic. The Army School of Nursing continued accepting students, and continued to organize additional nursing units, including new units in Texas, New York, and Georgia.

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918

Army School of Nursing Dean Annie Goodrich sent an urgent message to students accepted to the school, asking prospective students how soon they would be able to start.In the late summer and early autumn of 1918, a rare and highly contagious form of influenza (flu) incapacitated communities around the world. To complicate the situation, several thousand of the world’s top doctors and nurses were serving in Europe to support the troops abroad, leaving few to cope with a major epidemic at home, including the United States. Army School of Nursing Dean Annie Goodrich sent an urgent message to students accepted to the school, asking prospective students how soon they would be able to start (Condé, 1975). Dorothea Hughes, a student from the Army School of Nursing, writes:

In September the influenza epidemic came. The camp hospitals were suddenly filled with sick and dying men, and an emergency more pressing than that caused by the war was upon us. Calls were sent out to scores of us who were still awaiting orders, telling us to report for immediate duty. There was a response of 100 percent. We can be proud of that (Hughes, 1921, p. 32).

Fortunately, these women’s sense of patriotism did not end at the armistice. Students continued to flow into the school to learn and help as much as they could during this national health crisis.

The flu epidemic hit military bases especially hard, including Kansas’s Camp Funston, home to the largest cavalry post in the United States and several thousand troops (Condé, 1975). The Army School of Nursing students arrived shortly before the flu, and were just beginning their training when the epidemic hit the encampment. Gilberta Durland was one of the students training at Camp Funston’s Fort Riley, and remembers:

The ambulance made its daily or semi-daily trip to our quarters and carried off sometimes one, two, and three of our members. Four of our little band never returned. Our acquaintance with them was brief but still our work had, in even so short a time, drawn us closely to one another and they were greatly loved and missed by all (Durland, 1921, p. 215).

The flu epidemic peaked at Fort Riley between September 15th and November 1st, 1918. During this time period over 15,000 persons were treated at camp and base hospitals, with 5,368 treated at emergency hospitals in Camp Funston, 697 at the Officer’s Training Camp, and 9,105 at the Base Hospital at Fort Riley. Of those treated for influenza, 2,624 developed pneumonia (17.2%), and 941 (35.8% of those that developed pneumonia) died (Frick, 1918c). The vast majority of those who died were not the very young or very old, but young, strong, healthy men and (a few) women who were preparing to fight for and serve their country. Almost one of every four people stationed at the camp developed influenza, and the overall death rate was 6.2% (Stone, 1918).

Considering that the normal capacity for the base hospital was 3,068 beds, the medical department had to find creative ways to house patients without overcrowding the wards and potentially worsening transmission and exposure. Additional bed space was created by putting patients on the porches and corridors of the convalescent sections of the hospital, and using the porches of barracks and the YMCA building (Stone, 1919). This allowed regular airflow, decreasing the risk of transmission to hospital staff, nurses, and physicians, as well as other patients.

Despite these measures, the epidemic worsened and eventually peaked during the first weeks of October. There were 5,666 patients hospitalized on October 8th, putting the medical department at 185% of its capacity. Colonel Frick, the commanding officer of the medical department at Fort Riley sent a telegram to the U.S. Surgeon General requesting additional graduate nurses to supply the base hospital and emergency hospitals. He reported that 37 nurses were out sick just that day (Frick, 1918a). The Acting Surgeon General responded by sending 20 nurses from Letterman Hospital in San Francisco to Fort Riley Kansas; however, it would take several days for these reinforcements to arrive (Acting Surgeon General, 1918).

Assuming that nurses worked twelve hour shifts every day, each nurse and student had a minimum of 31 patients, many of whom were severely ill.As October continued without much relief from the epidemic, Frick sent another telegram to the Surgeon General on October 19th, factually explaining the circumstances of the nursing shortage. He stated that he currently had 3,829 patients and 272 Army nurses, 21 civilian emergency nurses, 13 nurse’s aides, and 36 students. Of these, 49 nurses, three aides, and three students were sick (Frick, 1918b). Assuming that nurses worked twelve hour shifts every day, each nurse and student had a minimum of 31 patients, many of whom were severely ill. This dire need for nurses was not unique to Fort Riley. Military encampments and communities across the country were in desperate need of nurses and trained medical assistants to comfort and treat the millions suffering from influenza.

Despite little to no experience in nursing, the students of the Army School of Nursing worked alongside the Army nurses to provide the best care that they could for the sick soldiers. Tragically, three students at Fort Riley, Alice Baker (died October 26, 1918), Fyvie Horne (died October 28, 1918), and Christine Colburn (died November 6, 1918) lost their lives from the flu. Across all of the training sites for the Army School of Nursing, twenty-four students died during training, with over half dying between October and December of 1918 (Army School of Nursing, 1921).

Following the end of World War I and the influenza epidemic, the need for soldiers, Army nurses, and Army student nurses, decreased dramatically. Student training sites were consolidated, and the students from Fort Riley were transferred to other base hospitals in March of 1919 (Durland, 1921). Many students chose to leave the school altogether; perhaps to reclaim their pre-war lives and dreams, or to continue nurse training closer to home. However, the work of these student nurses was not forgotten or overlooked by those in the Army Medical Department. The Hospital Breeze, Fort Riley’s newsletter, called the students “‘real soldiers.’ It said, ‘Patriotism was the force which drove their eager but untrained hands through the horror of the epidemic.’” (Condé, 1975, p. 39).

Despite challenges and heartbreak, the Army School of Nursing was a success.Despite challenges and heartbreak, the Army School of Nursing was a success. Students were able to be quickly mobilized to support the operations of the base hospital during the epidemic. This happened because of prior mobilization and willingness to serve in World War I, giving students training and exposure to emergency and disaster conditions that would prove invaluable in coming wars or disasters that would impact their own communities.

Conclusion

The Army School of Nursing was the nation’s first attempt at a military-based training school for nurses in the United States. Applicants differed from the traditional, newly graduated, high school females. Graduates included Mary Tobin, Dean of Duquesne University; Margaret Tracy, Dean of the predecessor of the University of California San Francisco; Helena Clearwater, Chief Nurse at Schofield Hospital, Oahu, Hawaii, during the bombing of Pearl Harbor; and Virginia Henderson, world renowned nurse educator (Army School of Nursing, 1921). The civilian and military leaders born of this novel program were a testament to its success in preparing high-quality nurses for the profession in a time of dire need.

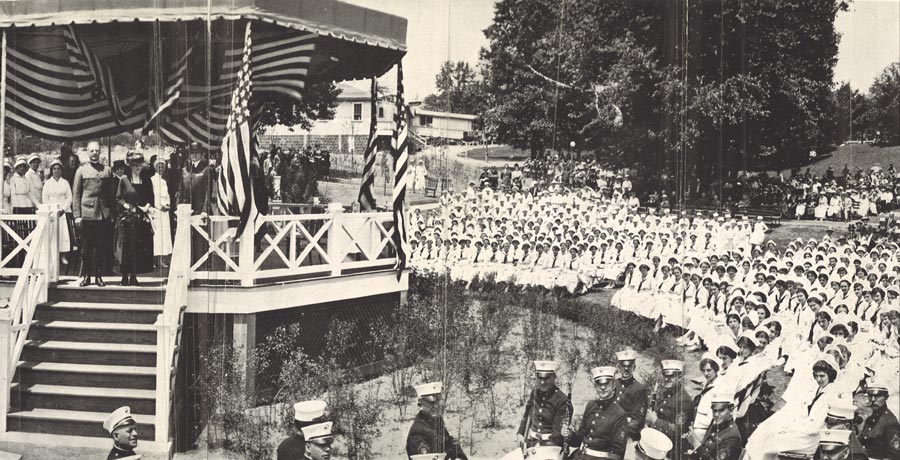

The civilian and military leaders born of this novel program were a testament to its success in preparing high-quality nurses for the profession in a time of dire need.The class of 1921 was also the first group of students trained under government control, and the only to be trained under wartime conditions. This was the largest class of nursing students to date to graduate from a school of nursing, and the first instance where the primary focus of nurse training was to educate and prepare high-quality nurses, rather than provide a cheap source of hospital labor (Sarnecky, 1999). Despite being stationed across the country, students maintained a sense of comradery and connectedness (Photo 2).

Photo 2: Class of 1921 Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington DC (1921).

Midwest Nursing History Research Center, University of Illinois Chicago College of Nursing (Used with permission)

Due to financial concerns following the crash of the U.S. stock market in the early 1930s, the Army School of Nursing was closed in 1933. However, according to Army historian Mary Sarnecky, had the Army School of Nursing "not been sacrificed on the altar of economy and political intrigue and had survived as a small unity capable of rapid expansion in time of need, perhaps the dilemma of inadequate nurse power experienced during World War II might not have come to pass. Moreover, as a shortage of nurses reappeared cyclically, such a resource could have served as a recruiting tool used to prepare nurses for the military" (Sarnecky, 1999, p. 154).

Despite its closure, the Army School of Nursing illustrates the ability of the profession of nursing to address health care challenges and inform the profession independently.Indeed, following the closure of the school, its re-establishment was consistently mentioned when considering approaches to address the shortage of nurses in the Army. The school was considered as a viable option in the 1940s in preparation for World War II, in the 1950s within context of the Korean War, as well as in 1958 when the Army had difficulty recruiting nurses (Sarnecky, 1999). However, it was never re-established.

Despite its closure, the Army School of Nursing illustrates the ability of the profession of nursing to address health care challenges and inform the profession independently.Despite its closure, the Army School of Nursing illustrates the ability of the profession of nursing to address health care challenges and inform the profession independently. Students in the Army School of Nursing, as many other military nurses who had come before them, were able to rise up and meet the needs of their patients and their country in times of national crises.

Author

Gwyneth Milbrath, PhD, RN, MPH

Email: gwyneth@uic.edu

Gwyneth Milbrath is a Clinical Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois Chicago College of Nursing. As a nurse historian she has researched the roles of military nurses in war and historical disasters. To date, her scholarship has been focused on the role of the nurses during the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and her current project, investigating the Army School of Nursing. She also currently serves as the First Vice President of the American Association for the History of Nursing.

References

Acting Surgeon General. (1918). Untitled. Record Group 112, Entry A1-31N, Box 264. Folder 211: Nurses. Series Correspondence 3/1/1917 – 9/30/1927. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Army School of Nursing. (1921). Those who died in service. Army School of Nursing Yearbook, 1921, p. 37. Midwest Nursing History Center, Chicago IL.

Condé, M. (1975). The lamp and the caduceus: The story of the Army School of Nursing. United States of America: Army School of Nursing Alumni Association.

Connolly, C. A. (2004). Beyond social history: New approaches to understanding the state of and the state in nursing history. Nursing History Review, 12(1), 5-24.

Durland, G. (1921). Fort Riley. Army School of Nursing Yearbook, 1921, p. 215. Midwest Nursing History Center, Chicago IL.

Frick, E.B. (1918a). Telegram from Frick to Surgeon General US Army dated 8 Oct 1918 3:50pm. Record Group 112, Entry A1-31N, Box 264. Folder 211: Nurses. Series Correspondence 3/1/1917 – 9/30/1927. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Frick, E.B. (1918b). Telegram from Frick to Surgeon General US Army dated 19 Oct 1918 7:20pm. Record Group 112, Entry A1-31N, Box 264. Folder 211: Nurses. Series Correspondence 3/1/1917 – 9/30/1927. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Frick, E.B. (1918c). Inquiry, Dec. 10, 1918, relative to influenza epidemic. Record Group 112, Entry A1-31N, Box 274. Folder 710: B.H. Ft. Riley, KS. Series Correspondence 3/1/1917 – 9/30/1927. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Hughes, D.M. (1921). History of the Army School of Nursing. Army School of Nursing Yearbook, 1921, p. 30 - 34. Midwest Nursing History Center, Chicago IL.

Sarnecky, M.T. (1999). A history of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sterner, D. (1996). In and out of harm’s way: A history of the Navy Nurse Corps. Seattle, WA: Peanut Butter Publishing.

Stone, C.J. (1919). Influenza. Record Group 112, Entry A1-31N, Box 264. Folder 211: Nurses. Series Correspondence 3/1/1917 – 9/30/1927. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.