American nurses (3.06 million) are at high risk for being overweight, as the majority are post-menopausal women (93.3% female; mean age 47). Studies have indicated that more than half of all nurses are either overweight or obese. This fact is of concern because nurses often lead major health promotion efforts. The aim of this study was to examine the feasibility of a novel participant-centered weight management program (PCWM) among nurses. The participant-centered (P-C) theoretical framework used originated from the field of usability engineering (i.e., user-centered design). Study methods included a single group pre-test/post-test design (baseline, eight weeks, three months) and an intervention consisting of face-to-face education sessions, technology-augmented exercise programs, and an eHealth portal. The results demonstrated a significant decrease in body weight, increased fruit and vegetable consumption, and increased exercise at eight weeks. In our discussion of this study, we note that although the intervention effects decreased at three months, these results are promising, considering that the intervention used was not regimented and relied only on nurses’ activation of their planned health behaviors. The major limitation of the study was the small sample size recruited from one large community hospital. Further research is needed to improve the sustainability of the program.

Key words: Overweight, obesity, weight management, nurse’s health, health promotion, participant-centered approach, Wii, motivation, exercise, diet, technology-based intervention

American nurses, the largest group of healthcare professionals...represent one illustrative population of older women at risk for overweight and obesity. Overweight and obesity are significant public health problems, affecting 68% of American adults (HBO Documentary Films, 2012; Institute of Medicine, 2010a; National Center for Health Statistics, 2009). Overweight people are at a higher risk for many chronic illnesses (Center for Disease Control and Intervention, n.d.; Hunskaar, 2008; Qin, Knol, Corpeleijn, & Stolk, 2010). In 2008, the per-person direct medical cost of obesity was $1,723 (Institute of Medicine, 2012; Tsai, Williamson, & Glick, 2011). Despite increased evidence of effective preventive measures, such as diet and exercise, obesity rates continue to rise (Barte et al., 2010; Institute of Medicine, 2010a; National Institutes of Health, 2012; Qin et al., 2010; Sodlerlund, Fischer, & Johansson, 2009; Tanne, 2010). Postmenopausal women are especially prone to weight gain and other health problems. American nurses, the largest group of healthcare professionals (3.06 million) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010; U.S. DHHS Health Resources and Services Administration, 2010), represent one illustrative population of older women at risk for overweight and obesity. They, as a profession, are predominantly female (93.3%) and rapidly aging (Cochran, 2010; Gambino, 2010; Twigg, Duffield, Thompson, & Rapley, 2010). The average age of nurses is 47, and the majority of these individuals do not plan to retire soon.

...nurses often neglect to take care of their own health. Although limited, recent studies have indicated a high prevalence of overweight nurses, 54% (N = 760) to 65% (N = 187) (Miller, Alpert, & Cross, 2008; Nahm, Warren, Zhu, An, & Brown, 2012; Zapka, Lemon, Magner, & Hale, 2009; Zitkus, 2011). Other studies have suggested that many clinicians lack knowledge about weight management (Forman-Hoffman, Little, & Wahls, 2006; Miller et al., 2008). Additionally, nurses often neglect to take care of their own health (American Association of Colleague of Nursing, 2008). For example, 21.7% of participants in a survey of 394 Icelandic nurses reported poor or very poor physical health, lack of regular exercise, and trouble sleeping (Sveinsdottir & Gunnarsdottir, 2008). Some female nurses (age 40-60) expressed "feeling uncared for" and had problems with "adapting to ageing" (Gabrielle, Jackson, & Mannix, 2008). From a public health perspective, these trends are significant because nurses serve as an important source of health information for the public (Institute of Medicine, 2010b; Miller et al., 2008) and often lead current efforts in obesity prevention (Nahm et al., 2012).

The purpose of this study was to examine the feasibility of a novel participant-centered weight management (PCWM) intervention program, comprised of Wii (Nintendo, 2010) exercise programs (e.g., boxing, tennis) and dance exercises on nurses’ stress and weight management. Considering that nurses are healthcare providers who promote health behaviors, this eight-week intervention was developed following the User-Centered Design (UCD) approach (Shneiderman, 2002; Usability Professionals' Association, 2010) that engages participants in the identification of problems as well as the requirements for the intervention. This will be referred to as the “participant-centered approach.” The study was conducted using a one group pre-test/post-test design with three observations: baseline, end-of-treatment, and three-month follow up. The primary outcomes included weight, activity behaviors, stress, and job satisfaction.

Background

Health Promotion Issues Among Nurses: Obesity, Stress, and Physical Activities

The unpredictability of work situations and highly time-sensitive nature of nurses’ work can affect their meal patterns in particular. High levels of stress have been a significant health problem for nurses (Dawson et al., 2007; McVicar, 2003; Ressler, 2007; Schulte et al., 2007). The main sources of stress include workload and the emotional cost of caring (McVicar, 2003). The unpredictability of work situations and highly time-sensitive nature of nurses’ work can affect their meal patterns in particular. As a result, nurses often choose to skip lunch and/or breaks to complete their work (King, Vidourek, & Schwiebert, 2009). In our preliminary study, 54.1% (n = 99) of nurses reported having irregular meals due to work, and there was a significant positive correlation between BMI and irregular meals (r = 0.21, p = .004) (Nahm et al., 2012). Long work hours and shift work are known barriers to nurses’ health (Keller, 2009; Lamond et al., 2003). Furthermore, these working conditions tend to have a more negative effect on older nurses (Lamond et al., 2003; Muecke, 2005). Nevertheless, findings have shown that nurses prefer 12-hour shifts (Montgomery & Geiger-Brown, 2010; Trinkoff, Geiger-Brown, Brady, Lipscomb, & Muntaner, 2006). Prior findings indicated that nurses with high levels of job stress have higher rates of eating disorders (King et al., 2009). Many tend to seek “comfort food” after stressful work (McVicar, 2003; Ruotsalainen, Serra, Marine, & Verbeek, 2008). Nurses must recognize their untoward process and learn to consciously make healthy dietary choices.

Long work hours and shift work are known barriers to nurses’ health. Although there is a general perception that nurses “walk a lot,” 71.9% (n = 123) of nurses in our preliminary study reported a lack of exercise (Nahm et al., 2012). In another study (N = 394) (Sveinsdottir & Gunnarsdottir, 2008), 21.7% (n = 85) of nurses reported the same issues. Exhaustion and lack of time were frequently cited reasons (Sveinsdottir & Gunnarsdottir, 2008). Generally, nurses in acute settings walk more than two miles per 12-hour shift (distances vary depending on unit design and patients’ needs) (Allnurses.com, 2009; Donahue, 2009; Welton, Decker, Adam, & Zone-Smith, 2006). In one study, the mean distance walked by RNs (N = 146) during a 12-hour shift in four adult medical-surgical units was 8,748 ± 2,953 steps (4.1 ± 1.4 miles) (Welton et al., 2006). Health benefits of nurses’ walking during working shifts still remain unclear.

Health Promotion Interventions in Work Places: A Paucity of Studies in the Nurse Population

Several large-scale health promotion studies conducted in work places have shown positive effects on employee diet and physical activities (Akers, Estabrooks, & Davy, 2010; Cook, Billings, Hersch, Back, & Hendrickson, 2007). These studies, however, have focused mainly on non-healthcare workers.

It is necessary to implement stress and weight management modalities that can be integrated into nurses’ daily lives and the hospital workflow. A few small studies have investigated the effects of exercise programs or complementary therapies for nurses (Raingruber & Robinson, 2007; Yuan et al., 2009). However, these studies rarely focused on weight management. More studies have been conducted related to managing stress (Mimura & Griffiths, 2003). For example, after a review of 77 studies, Edwards and Burnard (2003) suggested a few effective strategies for stress reduction in nurses, such as relaxation. The authors also identified a limitation in translating these study findings into practice settings. Considering the increasing patient acuity levels in hospitals, workplace stress and demands will continue to rise for nurses, while the population of nurses continues to age. It is necessary to implement stress and weight management modalities that can be integrated into nurses’ daily lives and the hospital workflow.

Weight Management Interventions: Strategies to Improve Engagement and Adherence

A gap exists between efficacious interventions in research settings and their practical use in real-life. Many studies have shown that behavioral interventions have some effectiveness on weight management (Brunner, Thorogood, Rees, & Hewitt, 2009; Lombard, Deeks, & Teede, 2009; Shaikh, Yaroch, Nebeling, Yeh, & Resnicow, 2008; Sodlerlund et al., 2009). Engagement of participants and their adherence to interventions have been reported as major challenges in those studies (Lombard et al., 2009; Sodlerlund et al., 2009). A gap exists between efficacious interventions in research settings and their practical use in real-life (Institute of Medicine, 2010a; National Institutes of Health, 2009). Researchers have begun exploring innovative approaches to translate interventions into individuals’ daily lives (Rhodes, Fiala, & Conner, 2009; Rhodes, Warburton, & Murray, 2009). Some studies have shown that affective judgment (e.g., enjoyment) is an influential factor for individuals’ health behaviors (Hu, Motl, McAuley, & Konopack, 2007; Rhodes, Fiala et al., 2009). A systematic review of 102 studies showed a significant relationship between physical activities (PA) and affective judgment expected from performing PA (Rhodes, Fiala et al., 2009). Other studies have demonstrated that participants who had multiple choices in exercise interventions showed better adherence than those who had only one option (Thompson & Wankel, 2006). To date, behavioral interventions in studies have primarily been prescribed by experts and rarely emphasize participants’ affective judgment. To develop behavioral interventions that can engage participants for the long term, affective judgment should be considered.

Theoretical Framework and Its Application to the Study

The majority of participants had used multimedia-based exercise programs, such as exercise DVDs and Wii exercise games, and were open to using those activities. Considering nurses’ expertise, compared to laypersons in the practice of health promotion, the presented novel intervention focused on the initial motivation of nurses to practice their preferred health activities and to provide resources and interesting activity options. The participant-centered (P-C) framework, which originated from the field of usability engineering (i.e., user-centered design) (Shneiderman, 2002; Usability Professionals' Association, 2010), guided the study approach. The P-C framework values participant friendliness in the intervention and engages potential participants in the intervention development (Table 1). For instance, participants’ health problems with weight management and lack of activities were identified by our preliminary study about nurses' perception on health and health improvement needs (Nahm & Warren, September 2010). We then conducted a follow-up survey to identify nurses’ preferences and motivations for methods to solve the problems (Table 2) (Nahm et al., 2012). For diet, the most frequently preferred methods were related to the cafeteria food, regular meal times, and time to prepare meals, followed by resource guides, recipes, and supports. The selected hospital was making improvements in cafeteria foods at the system level; thus, our team focused on the other methods through education sessions and online resource information. For exercise, the most preferred exercises included using the treadmill or elliptical; yoga or Pilates; and dancing. The majority of participants had used multimedia-based exercise programs, such as exercise DVDs (n = 109, 64.5%) and Wii exercise games (n = 72, 42.6%), and were open to using those activities. In this pilot study, we focused on the provision of multimedia programs, such as Wii and DVDs for yoga, Pilates, dance, and exercise.

Table 1. The Participant-Centered Approach and Its Application to the Development of the Behavioral Intervention

|

P-C Approach |

Application of the Task in this project |

|

1. Specify the context (e.g., goals & conditions) for the program |

|

|

2. Specify user requirements |

|

|

3. Develop solutions |

|

|

4. Evaluate solutions |

|

Table 2. Preferred Approaches to Improve Diet and Exercise Behaviors (Nahm et al., 2012)

|

Category |

Comments |

Frequency |

|

|

Diet |

Better cafeteria food (availability and cost) |

40 |

|

|

Exercise |

Treadmill or elliptical |

105 |

|

|

Stress management Technique

|

Eat Exercise Relaxation techniques (tub bath, massage, meditation, yoga) Conversation with family members, friends, etc. Reading |

32 31 27 26 23 |

|

The intervention was designed to offer participants several options for exercise types. Upon selection of the exercise types, including Wii and exercise DVDs, 21 nurses at the hospital evaluated the intervention approaches (Nahm & Warren, September 2010). All participants reported that they would use the selected exercise programs if they were available on the unit. The majority of participants (N = 14, 67%) reported that the level of activity provided by Wii and DVD programs was appropriate for exercise activities. During testing, most participants mentioned having “fun” and experiencing “stress release.” The intervention was designed to offer participants several options for exercise types. This approach has been shown to improve individuals’ adherence to their exercise plans (Thompson & Wankel, 2006).

Study Methods

Design

The feasibility of the program was examined using a pre-test/post-test design on a small sample (N = 25). The primary outcomes included stress, weight, activity behaviors, and job satisfaction. The data were collected at three points (baseline, end-of treatment [EOT, 8-week], and at three months) via online survey. This study also identified potential issues for a future larger scale trial through qualitative analysis of narrative comments.

Sample

The eligibility criteria for the study included: (1) registered nurse (RN) who works at least 0.5 FTE at the Medstar Franklin Square Medical Center (MFSHC); (2) female gender; (3) age 45 years or older; (4) access to the Internet/e-mail; (5) ability to use the Internet/e-mail independently; and (6) BMI > 24. Participants were excluded if they: (1) were pregnant; (2) did not pass the PAR-Q (the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire) (American College of Sports Medicine, 2009; Thomas, Reading, & Shephard, 1992); (3) were currently participating in any study on: weight management, nutrition or exercise; and (4) required any of the following medical treatments: chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or hemo/peritoneal dialysis.

Upon approval from the Institutional Review Boards of the MedStar Health System and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, participants were recruited from MFSHC, a large community teaching hospital located in the state of Maryland. Participants were recruited for five weeks (3/30/2012–5/6/2012), using an e-mail listserv (all nurses in MFSHC use e-mail) and flyers in the nurses’ break rooms.

Intervention

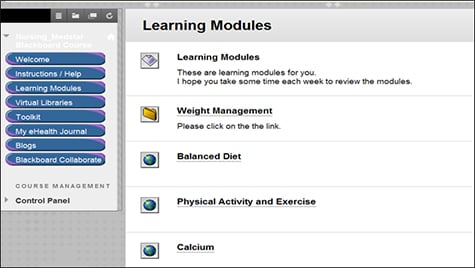

The eight-week program was comprised of three components: (1) two face-to-face (FTF) sessions (introduction, diet, and exercise); (2) Wii (Nintendo, 2010) exercise games (e.g., boxing, tennis) and various DVDs for dance exercises; and (3) an eHealth portal, including eHealth journals and other resource materials on balanced diet and exercise (Figure 1). The resource materials were optional and comprised of learning modules, virtual libraries, and blogs that were used by the nurses in the program.

|

Figure 1. Screen Shots of eHealth Portal |

|

|

|

All participants received a pedometer and a dance DVD of their choice. Group sessions and exercise media options. At the beginning, participants attended two FTF group sessions. Table 3 describes an overview of the intervention. Dieticians at the MFSMC and an exercise trainer who had worked with nurses in similar studies taught the FTF sessions. During these sessions, participants were also exposed to Wii programs and DVD programs. All participants received a pedometer and a dance DVD of their choice. In the second session, participants set their own activity goals under the guidance of the health coach (at least 150 minutes of moderate-level activities per week). Upon completion of the two sessions, they worked on their selected activities independently, at their convenience (e.g., at home or at work). Additionally, the nursing research department ran a DVD rental program (a total of 33 DVDs covering low, medium, and high impact exercises, such as weight- loss yoga, walk-away pounds, fat-burning dance aerobics, and kick-boxing; and participants were encouraged to rent these at no charge. The hospital also opened a nurses’ health lounge that was equipped with “Wii Sports” (Nintendo, 2014) programs with screens and DVD players, as well as a yoga mat.

Table 3. Overview of the Intervention

|

Week* |

Content |

|

Wk 1 (FTF) |

|

|

Wk 2 (FTF) |

|

| Wk 3 – 8 |

|

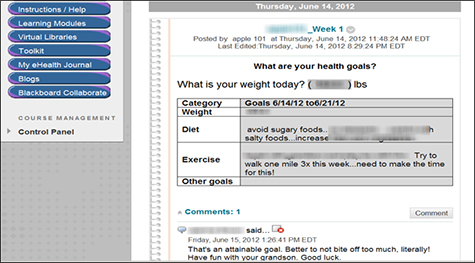

After participating in two FTF sessions, participants entered their health goals for the next four weeks into the goal section of the eHealth journal. eHealth portal. An eHealth portal was developed as a health community for nurses using the Blackboard (BB) Program (Blackboard Inc., 2010) and web pages for resource materials. Secure personal journals and blogs were part of the BB components. After participating in two FTF sessions, participants entered their health goals (exercise, diet, and other goals) for the next four weeks into the goal section of the eHealth journal. They were encouraged to evaluate progress toward the goals at least weekly using a Goal Attainment scale (Kiresuk & Sherman, 1968) incorporated in the eHealth journal. This scale assesses the effect of the intervention on individual goals and has been used successfully in our prior online studies (Nahm et al., 2010; Nahm et al., In Press). On the fifth week, participants were asked to revisit their goals and modify as needed. The health coach, a registered nurse with extensive experience in similar online health programs, reviewed the participants’ progress journals and provided motivational comments based on the Journal Operation Procedures. She also consulted expert panel members as needed.

Use of blogs and resources was optional. All participants were able to create new blogs and post comments. Other resource programs included learning modules (e.g., weight management, balanced diet, physical activity/exercise, calcium/vitamin D), a tool kit (e.g., food and exercise diaries, BMI calculator), and a virtual library on relevant topics. The majority of the learning materials were developed and tested in our prior projects and modified as needed for this project (Nahm et al., 2010; Nahm et al., In Press). During the initial orientation process, participants were encouraged to use these additional resources. In particular, the use of blogs was highlighted as a peer-support forum.

Procedures. After consenting, participants were placed on a waiting list. At the end of the recruitment period, they were contacted via e-mail and given a user ID, a password, and the link to the baseline survey (one week). Upon completion of the survey, participants attended two FTF sessions. Each session was offered twice (early morning and late afternoon) to accommodate nurses’ schedules, and sessions were videotaped. The videos were uploaded on the eHealth portal (one nurse missed the dietary session and watched the video session), and participants learned to use the portal resources (e.g., eHealth journal, blogs) during the introduction session. The first session was comprised of this introduction and a lecture on healthy diet behaviors, focusing on nurses’ life styles, such as meal times, skipping meals, and snacking.

The second session focused on physical activities and exercise, and demonstrated use of Wii exercise games and dance exercise DVDs. A simple step-by-step instruction tip sheet for the Wii program was distributed. The intervention emphasized peer motivation, thus a small group approach was applied. The 12 and 13 participants who took the FTF sessions together started the intervention as a group (intervention period: May 31, 2012 to August 5, 2012).

After the second session, participants were asked to enter health goals for exercise and diet in their eHealth journal. The health coach again provided online comments. In addition, they were encouraged to use the health lounge for their workouts at their convenience and to try out new videos. At the end of the intervention and at the three month follow up, participants were provided a link to an online survey. One week was given to complete the survey.

Treatment fidelity. Among different areas of treatment fidelity discussed by Bellig et al. (2004), we assessed the (1) delivery of treatment; (2) receipt of treatment; and (3) enactment of treatment skills. The first was assessed by the usage of the program via BB analytic reports such as the frequency of the postings, and qualitative comments. The second was assessed by the activity level captured by the pedometer (SureSource LLC, 2010). The third was assessed by the participants’ maintenance of their planned activities using the self-reported scores in the survey and weight measures.

Measures

At baseline, participants provided information about demographics (e.g., age, sex, education, and years of internet experience), medication, chronic diseases, and recent acute illnesses (cardiac events, infections, musculoskeletal or neurological events).

Physical measures. Trained health coaches assessed height, weight, and waist circumference. Height was measured using a portable stadiometer, and weight was measured with a calibrated scale based on the measurement protocol. Heights and weights were converted into a BMI score. Waist circumference (WC) was measured at a level midway between the lower rib margin and iliac crest in accordance with the protocol (Nadas, Putz, Kolev, Nagy, & Jermendy, 2008).

Stress. The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used to assess the nurses’ level of stress (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983; Cohen & Williamson, 1988). This scale has previously been used for nurse participants (Cuneo et al., 2010). Prior findings provided some evidence of concurrent and predictive validity. The calculated α coefficient ranged from .71 to .86 (Cohen & Williamson, 1988; Cuneo et al., 2010).

Dietary behavior. We used the Rapid Block Food Screener (Block, Gillespie, Rosenbaum, & Jenson, 2000), including a 15-item Block Fat Screener and a seven-item Block Fruit-Vegetable Screener. Prior findings showed adequate predictive validity (King et al., 2009).

Exercise behavior. Exercise behavior was assessed using the Yale Physical Activity Survey (YPAS) (Dipietro, Caspersen, Ostfeld, & Nadel, 1993) and the pedometer (Omron HJ-112 (SureSource LLC, 2010). The YPAS is a 27-item questionnaire, including five categories of common groups of work, exercise, and recreational activities performed during a typical week. This measure has shown stability (r = .63) (Dipietro et al., 1993) and has been validated against several physiological variables (Dipietro et al., 1993; Pescatello, DiPietro, Fargo, Ostfeld, & Nadel, 1994). Participants wore the Omron HJ-112 Pedometer for seven days except while sleeping or during water activities. Participants were instructed to wear it when the online survey started (open for seven days) and bring it to the health coach for a reading when they came to measure their body composition. Prior findings showed acceptable interdevice reliability (r = 0.8), and the pedometer has been validated against other criterion measures (Hasson, Haller, Pober, Staudenmayer, & Freedson, 2009; Holbrook, Barreira, & Kang, 2009).

Job satisfaction. We assessed job satisfaction using the seven-item Job Enjoyment Scale of the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI®) (α= .91-.92) (American Nurses Association, 2009; NDNQI, 2010; Montalvo, 2007). MFSMC conducts this survey every other year (MedStar Health, 2010).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, frequency, percentage) were computed on demographic data, other job-related characteristics and intervention usages. Qualitative comments were analyzed, using frequency and content analysis. Exploratory data analysis was performed on each variable to assess normality and to ensure that analysis model assumptions were adequately met. Transformations were used for several continuous outcome variables to correct skewness. Linear mixed models growth curve analyses were used to examine changes in outcome variables over the course of the study. The linear component tests for a linear trend in the outcome over time and the quadratic component tests for a peak shaped pattern of changes in the outcome over time. A quadratic effect indicates a peak; a negative coefficient indicates an inverted crest. Examination of outcomes began with fixed effects only, proceeded to random intercept, and finally random intercept/random slope models. Separate analyses were conducted for each outcome, and information criteria were used to compare models within outcomes.

Results

Demographics

Table 4 summarizes demographic characteristics of the participants. The majority were white with a mean age of 54.8. Most nurses were direct care providers working an eight-hour fixed shift. More than half of the nurses had an associate or diploma degree and six (24%) had a baccalaureate degree. The average years of web use was 12.6, and the majority of participants perceived that their level of computer knowledge was advanced beginner or competent. The average baseline BMI was 31.73, and the mean number of steps per day was 7,504.02. Yale exercise minutes per week were 130.8.

Table 4. Participant Demographics

|

Characteristics |

|

N |

n (%) or M + SD

|

|

Age (M + SD) |

|

25 |

54.76 ± 6.05 |

|

Ethnicity |

African American |

|

1 (4.00) |

|

White

|

|

24 (96.00) |

|

|

BMI

|

|

25 |

31.73 ± 4.77 |

|

Mean Steps

|

|

24 |

7,504.02 ± 2,406.36

|

|

Chronic Illnesses

|

High BP |

25 |

5 (20.00) |

|

Heart |

25 |

1 (4.17) |

|

|

Diabetes |

25 |

3 (12.00) |

|

|

Depression |

25 |

4 (16.00) |

|

|

Osteoporosis |

25 |

2 (8.00) |

|

|

Highest nursing degree |

Associate degree |

25 |

6 (24.00) |

|

Diploma degree |

|

8 (32.00) |

|

|

Baccalaureate degree |

|

9 (36.00) |

|

|

Master’s degree

|

|

2 (8.00) |

|

|

Position |

Administration |

25 |

3 (12.00) |

|

|

Direct care RN |

|

18 (72.00) |

|

|

Prof. development specialist |

|

2 (8.00) |

|

|

Other

|

|

2 (8.00) |

|

Shift |

8-h rotation shift |

24 |

1 (4.17) |

|

|

8-h fixed shift |

|

19 (79.17) |

|

|

12-h-fixed shift |

|

3 (12.50) |

|

|

Irregular shift

|

|

1 (4.17) |

|

Ethnicity |

African American |

|

1 (4.00) |

|

|

White

|

|

24 (96.00) |

|

Highest degree |

Associate degree |

25 |

6 (24.00) |

|

|

Diploma degree |

|

8 (32.00) |

|

|

Baccalaureate degree |

|

9 (36.00) |

|

|

Master’s degree

|

|

2 (8.00) |

|

Web experience (years)

|

|

24 |

12.60 ± 5.39 |

|

PC knowledge |

Beginner |

25 |

2 (8.00) |

|

|

Advanced beginner |

|

8 (32.00) |

|

|

Competent |

|

9 (36.00) |

|

|

Proficient |

|

6 (24.00) |

The most frequent chronic illness was high blood pressure. On average, participants’ diet was high in fat and their fruit and vegetable consumption was similar to most Americans. The mean stress score was 20.84 and the average job satisfaction score was 31.28.

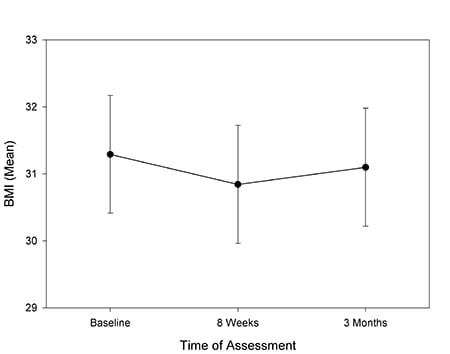

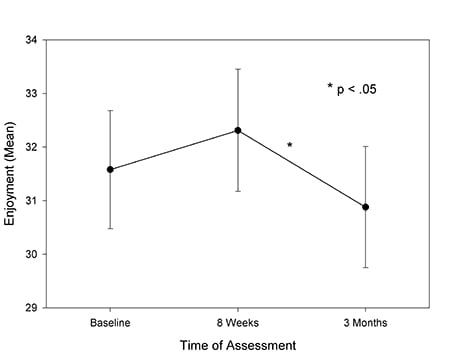

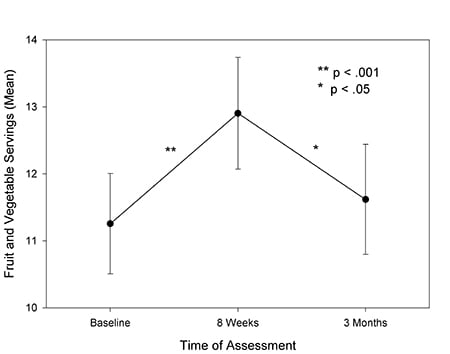

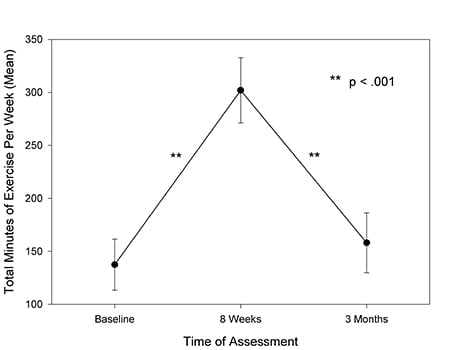

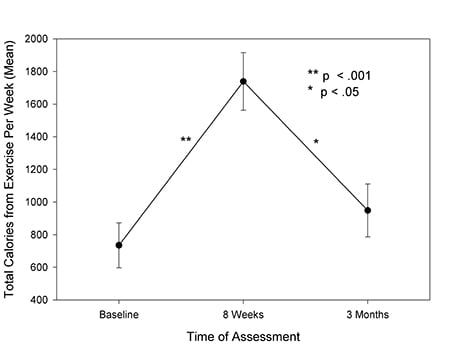

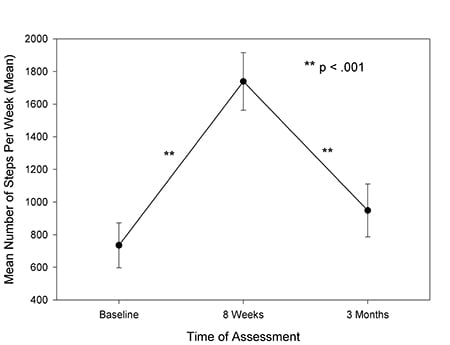

A total of 20 participants (80%) participated in the baseline data collection followed by 18 (72%) at three months. Linear mixed models have the advantage of including all data from incomplete as well as complete cases and provide unbiased estimates as long as the data are missing in a non-informative manner (Singer & Willett, 2003), which was the case in this data set. In linear mixed models, analyses with random intercepts, BMI, fruit and vegetable servings, Yale total minutes of exercise, and Yale calories of exercise all increased significantly from baseline to the end of the intervention and returned toward baseline after the conclusion of the intervention (Table 5). None of them remained significantly above baseline at 12 weeks (see Figure 2). Mean number of steps demonstrated no significant increase during the intervention and a significant decrease after the intervention.

Table 5. Estimates of Difference From Baseline in Mean Value of Each Outcome at End of Eight Week Intervention and 12 Weeks After the End of the Intervention

|

Outcome Parameter |

Estimate (95% CI) |

Std. Error |

df |

t |

Sig. |

||

|

BMI |

|

||||||

|

8 weeks |

-.444 (-0.748-0.141)** |

0.150 |

39.1 |

-2.959 |

0.005 |

|

|

|

12 weeks |

-.184 (.500-.132) |

.156 |

39.1 |

-1.175 |

.247 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enjoyment |

|

||||||

|

8 weeks |

.839 (-0.628-2.306 |

0.724 |

36.8 |

1.159 |

0.254 |

|

|

|

12 weeks |

-.583 (-2.018-0.852) |

0.708 |

36.8 |

-.823 |

0.416 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stress |

|

||||||

|

8 weeks |

-.546 (-2.806-1.714) |

1.120 |

42.4 |

-.487 |

0.629 |

|

|

|

12 weeks |

1.310 (-0.912-3.532) |

1.101 |

41.6 |

1.190 |

0.241 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fat |

|

||||||

|

8 weeks |

-1.958 (-4.534-0.619) |

1.274 |

38.9 |

-1.537 |

0.132 |

|

|

|

12 weeks |

-1.406 (-3.928-1.116) |

1.247 |

38.8 |

-1.128 |

0.266 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fruit and Vegetables |

|

||||||

|

8 weeks |

1.650 (0.222-3.078)* |

0.705 |

38.0 |

2.339 |

0.025 |

|

|

|

12 weeks |

.363 (-1.035-1.760) |

0.690 |

38.0 |

0.525 |

0.603 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exercise minutes/week |

|

||||||

|

8 weeks |

152.260 (59.856-244.663)** |

36.832 |

34.6 |

4.134 |

< 0.001 |

|

|

|

12 weeks |

48.515 (-45.670-142.699) |

37.592 |

35.6 |

1.291 |

0.082 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exercise Kcal / week |

|

||||||

|

8 weeks |

916.200* (393.448-916.200)* |

211.610 |

50.0 |

4.330 |

< 0.001 |

|

|

|

12 weeks |

382.714 (150.818-382.714) |

215.973 |

50.0 |

1.772 |

0.228 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mean Steps/day |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

8 weeks |

173.530 (-1583.129-1930.188) |

705.293 |

40.4 |

-1583.129 |

0.993 |

|

|

|

12 weeks |

-2292.874* (-4188.171-397.576)* |

762.121 |

41.9 |

4188.171 |

-0.013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

* < 0.05, ** <0.01

Note: A negative estimate indicates that the mean for this outcome was below the mean at baseline at the comparison time (8 or 12 weeks).

|

Figure 2. Estimated Mean (+/- sem) for Each Outcome at Baseline, Immediately Post Intervention (8 Weeks) and 12 Weeks Later |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Usage of the Intervention Components

More than half of the participants used the virtual libraries and blogs. All participants used the eHealth portal. For health goals, 21 participants (92%) entered their initial health goals into their own eHealth portal journal, and among those 10 revised their health goals at the fifth week. Table 6 summarizes the participants’ usage of other resource programs. Most of the participants used the learning modules on balanced diet and exercise and/or weight management. More than half of the participants used the virtual libraries and blogs. However, only 13 postings were posted by the participants. The majority of blog postings contained comments about the program (e.g., “... I am really excited about this program and really want to give it a good try.”)

Table 6. Other Resource Section

|

Resource Component |

Frequency (number participants) |

|

Virtual libraries |

54 (n = 13, 52%) |

|

Balanced diet and activity learning modules |

91 (n = 22, 88%) |

|

Weight management module |

135 (n = 22, 88%) |

|

Blogs |

8 postings; (n = 13) |

Few participants used the health lounge, and they did not always document their visits on the attendance sheet provided. Few participants used the health lounge, and they did not always document their visits on the attendance sheet provided. Although it is likely that more participants used the health lounge, the usage still seemed minimal. Based on the qualitative comments, almost half of the participants (n = 8 out of 17; 47.1%) had the Wii program at home and 52.9% (n = 9 out of 17) had used DVDs at home. Ten participants commented that they either did not want to exercise at work or preferred to exercise at home. For the DVD rental program, in addition to each individual’s choice of a DVD at the start of the program, the participants borrowed an additional 25 DVDs during the trial phase.

Discussion

The study findings showed a significant decrease in body weight (mean change, 5 lbs; BMI, 0.6), increased fruit and vegetable consumptions (2.16 on the Block Fruit-Vegetable Screener score [range, 0-35]), and increased time spent exercising (161 minutes per week) at eight weeks. These are promising results, considering that the intervention required minimal supervision by the researchers and mainly relied on the nurses’ own execution of behavior changes. In particular, the July 4th holiday occurred toward the end of the intervention, and participants expressed challenges in controlling foods and exercise. It seems that the eHealth journal entries helped some participants stay on track.

Findings from the fat consumption were informative. Based on the Block Fat screener (Block et al., 2000), participants’ consumed diets high in fat (17.84 ± 8.49). Although fat consumption was reduced (15.65 ± 8.17) at eight weeks, the changes were not significant. This may be a future target area for further education. Generally, participants reported having less chronic illnesses than those of the same age group (Table 4). The most frequent chronic illness was high blood pressure (n = 5, 20%), which was still less than the general population (31%, 67 million) in the United States (Center for Disease Control and Intervention, 2013). With changes in age, older nurses face increased risks for high blood pressure and cardiac illnesses. Although nurses may be well aware of the clinical impact of fat consumption and heart illness, they may need to evaluate their diet and make necessary adjustments.

The use of the pedometer fostered friendly competition and served as a linkage for peer support... The step counts, however, were considerably reduced at 12 weeks. Pedometer step counts increased by approximately 500 steps, however, the change was not significant. The pedometer could have served as a motivating factor at baseline data collection. Initially, we expected that step exercises might not be appealing to nurses since they usually stay on their feet for long hours and often walk a great deal on the unit. Based on the qualitative comments, however, nurses really liked the pedometers. The use of the pedometer fostered friendly competition and served as a linkage for peer support (i.e., nurses who worked on the same unit compared and challenged each other to increase their step counts). The step counts, however, were considerably reduced at 12 weeks.

These findings were consistent with many other behavior intervention studies (Bickmore et al., 2013; De Greef, Deforche, Tudor-Locke, & De Bourdeaudhuij, 2010; Morey et al., 2009). In these reports, the length of the interventions varied, such as eight weeks (Bickmore et al., 2013), six months (De Greef et al., 2010) , or 12 months (Morey et al., 2009). The similarity of the findings was that participants’ health behaviors improved after the period of intensive interventions, then regressed. Anecdotal comments from nurses provided further insights on future interventions. For example, considering nurses’ general knowledge about balanced diets, exercise, and busy life schedules, we made efforts to minimize the number of FTF sessions by limiting it to two and tailored the content of the FTF sessions by adding practical cases applicable to nurses (e.g., packing healthy snacks that they could consume when work gets very busy or finding ways to maximize activity levels at work). Contrary to our initial assumption, nurses enjoyed the FTF sessions and wished for more of them. Only one nurse missed the first session and watched the video clip. We also hoped to see participants’ active blog entries. Only 8 postings were posted although more than half of the participants (n = 13) accessed the blogs. A few nurses commented that they were not familiar with blogs and recommended that the health coach moderate the blogs with helpful information from other blog sites.

Contrary to our initial assumption, nurses enjoyed the FTF sessions and wished for more of them. Considering the nurses’ preference for FTF sessions more than two FTF sessions may be helpful. For example, use of monthly brown bag lunches on nurses’ health behaviors can be part of their continuing education. These approaches may have a synergistic impact by combining healthy food with learning. Some participants commented that the health education material in the eHealth portal was useful for teaching patients.

In this study, most participants were white (96%), higher than the percentage of whites in overall nurses at the MFSHC (88.28%). Additionally, 96% were day-shift nurses. Traditionally, engaging night-shift staff in activities is difficult. Many elect to work nights because they have young children and/or other family obligations and often are not as engaged in work activities.

The intervention did not demonstrate its direct impact on stress or job satisfaction, which was expected. In this feasibility study, the intervention focused more on dietary and exercise interventions. In a future study, we plan to add an intervention that could alleviate nurses’ job-related stress levels.

Limitations

The major limitation of the study was the small sample size recruited from one large community hospital. The majority of participants were also white and day shift nurses. Further studies are needed with larger samples including minority nurses and nurses recruited from several hospitals. In addition, specific efforts are needed to recruit nurses working different shifts. The intervention of this study was not designed to deliver regimented behavior protocols. Rather, the modes and doses of the interventions varied depending on each participant. The major data collection method for dietary consumption and the amount of exercise was self-reported. Although the steps were counted using pedometers, there was no significant correlation between the amount of exercise and the number of steps. This could be due to the nature of nurses’ work (i.e., walking for a prolonged time during their shift). Findings showed that only fat consumption served as a moderator for the changes in BMI at eight weeks. Further investigation of nurses’ dietary consumption, as well as the effects of exercise and diet on their weight status, may provide helpful information to benefit many aging women still active in the work force.

Conclusion

... although nurses are healthcare providers, they need interventions to manage their own weight... hospitals can make a significant contribution to nurses’ health by introducing innovative interventions. Overweight and obesity are becoming a major health issue for nurses. Many are getting older and are subject to other illnesses as well. The PCWM intervention used in this study showed promising preliminary effectiveness. The importance of these findings is two-fold. First, although nurses are healthcare providers, they need interventions to manage their own weight. Second, hospitals can make a significant contribution to nurses’ health by introducing innovative interventions. Maintenance of sustained motivation is a challenging task; however, hospitals are well positioned to overcome this issue since they already have many experts to guide these efforts. Healthy nurses are good role models for patients and provide higher quality care. Further research is needed along with a heightened awareness regarding overweight and obesity among healthcare providers.

Authors

Eun-Shim Nahm, PhD, RN, FAAN

Email: enahm@son.umaryland.edu

Dr. Eun-Shim Nahm is a Professor and the Program Director for the Nursing Informatics program at the University of Maryland School of Nursing (UMSON) in Baltimore, MD. Her research focuses on the use of technology-based interventions to promote health and to manage chronic illnesses of older adults. She has conducted various studies in this field, including qualitative, measurement, theory testing, and usability studies, as well as randomized controlled trials. She has developed and successfully implemented online health behavior interventions for adults aged 50 and older and their caregivers. Dr. Nahm is the recipient of multiple grant awards from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). She has published more than 40 peer-reviewed journal articles and six book chapters. At the UMSON, Dr. Nahm teaches graduate-level nursing informatics courses and doctoral-level research courses and has mentored many graduate and doctoral students.

Joan Warren, PhD, RN-BC, NEA-BC

Email: joan.warren@medstar.net

Dr. Warren has been a hospital-based researcher and nursing leader for over 20 years. She successfully led two large hospitals to establish an evidence-based practice and research program for nurses. Her responsibilities have included oversight for nursing quality and patient safety programs, professional development programs for nursing staff, school of nursing affiliation agreements, grants and partnerships, and evidence-based practice and research. Dr. Warren was instrumental in the hospital’s achievement of initial Magnet® designation and re-designation. As a nurse researcher, she has been awarded grant funding from the Maryland Health Care Cost Review Commission to advance the professional nursing work force, as well as grants from the American Organization of Nurse Executives, National Nursing Staff Development Organization and the American Nurses Foundation. She was named the Julia Hardy, RN/ANF Scholar.

Erika Friedmann, PhD

Email: friedmann@son.umaryland.edu

Erika Friedmann, PhD, has been a Professor on the University of Maryland School of Nursing faculty since 2003. She is a member of the Centers of Excellence in Biology and Behavior Across the Lifespan and Health Systems Outcomes. She has extensive expertise in research methods and biostatistics and has served as the methodologist on several NIH funded grants. Dr. Friedmann is an active researcher, conducting NIH funded research, publishing over 100 papers in interdisciplinary refereed journals, and mentoring PhD students and faculty members. Her statistical proficiency includes modern regression methods applied to data analysis in the current study.

Jeanine Brown, MS, RN

Email: jbrown@son.umaryland.eduJeanine

Brown, MS, RN has a diverse career in direct patient care, health research, and care management. Ms. Brown obtained her master’s degree in Nursing Informatics. As health program manager for the Early Renal Insufficiency program at (UMMC), she worked closely with patients affected by diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. She has also served as research coordinator for a large online bone health study. In the present study, she served as project manager and supervised the field operation.

Debbie Rouse, RN-BC, VA-BC

Email: debbie.c.rouse@medstar.net

Debbie Rouse has worked for over 22 years as a professional Registered Nurse and has firsthand experience of the unhealthy behavior and habits that nurses often adopt. She participated in the study as a research nurse at MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center.

Bu Kyung Park, MS, RN

Email: bkpark0708@gmail.com

Bu Kyung Park is a PhD student and a research assistant in the School of Nursing at University of Maryland in Baltimore, MD. She has worked in various technology-based health interventions with Dr. Nahm and served as a research assistant for the present study.

Kyle W. Quigley, MBA, BS

Email: kyle.w.quingley@medstar.net

Kyle Quingley works as the Nursing Business Coordinator for the Nursing Research department at the MedStar Frankline Square Medical Center. He is responsible for the submission of IRB materials for review, and compliance. He also aids in the administering of the study through data collection and analysis, coordinating and interacting with study participants, and facilitating focus group sessions. He participated in this study as a research associate.

© 2014 OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

Article published September 30, 2014

References

Akers, J. D., Estabrooks, P. A., & Davy, B. M. (2010). Translational research: Bridging the gap between long-term weight loss maintenance research and practice. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(10), 1511-1522. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.005

Allnurses.com. (2009). Does working as a nurse count as exercise? Retrieved from http://allnurses.com/general-nursing-discussion/does-working-nurse-373154-page3.html

American Association of Colleague of Nursing. (2008). The essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from www.aacn.nche.edu/Education/pdf/BaccEssentials08.pdf

American College of Sports Medicine. (2009). ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

American Nurses Association. (2009). NDNQI® RN Survey. Retrieved from www.nursingquality.org/RNSurvey/Confidentiality.aspx

Barte, J. C., ter Bogt, N. C., Bogers, R. P., Teixeira, P. J., Blissmer, B., Mori, T. A., & Bemelmans, W. J. (2010). Maintenance of weight loss after lifestyle interventions for overweight and obesity, A systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 11(12), 899-906. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00740.x

Bellig, A. J., Borrelli, B., Resnick, B., Hecht, J., Minicucci, D. S., Ory, M., … Czajkowski, S. (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology, 23(5), 443-451. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443

Bickmore, T. W., Silliman, R. A., Nelson, K., Cheng, D. M., Winter, M., Henault, L., & Paasche-Orlow, M. K. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of an automated exercise coach for older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(10), 1676-1683. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12449

Blackboard Inc. (2010). Blackboard Academic Suite 9.1. Available: http://www.blackboard.com

Block, G., Gillespie, C., Rosenbaum, E. H., & Jenson, C. (2000). A rapid food screener to assess fat and fruit and vegetable intake. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 18(4), 284-288. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00119-7

Brunner, E. J., Thorogood, M., Rees, K., & Hewitt, G. (2009). Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002128.pub2

Center for Disease Control and Intervention. (2013). High blood pressure facts. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm

Center for Disease Control and Intervention. (n.d.). Overweight and obesity: Causes and consequences. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/obesity/causes/health.html

Cochran, J. H. (2010). A physician prescription for the nursing shortage. Permanente Journal, 14(1), 61-63.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R., (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385-396,

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Cook, R. F., Billings, D. W., Hersch, R. K., Back, A. S., & Hendrickson, A. (2007). A field test of a web-based workplace health promotion program to improve dietary practices, reduce stress, and increase physical activity: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 9(2), e17. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e17

Cuneo, C. L., Cooper, M. R., Drew, C. S., Naoum-Heffernan, C., Sherman, T., Walz, K., & Weinberg, J. (2010). The effect of reiki on work-related stress of the registered nurse. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 29(1), 33-43. doi: 10.1177/0898010110377294

Dawson, A. P., McLennan, S. N., Schiller, S. D., Jull, G. A., Hodges, P. W., & Stewart, S. (2007). Interventions to prevent back pain and back injury in nurses: A systematic review. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 64(10), 642-650. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.030643

De Greef, K., Deforche, B., Tudor-Locke, C., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2010). A cognitive-behavioural pedometer-based group intervention on physical activity and sedentary behaviour in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Health education research, 25(5), 724-736. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq017

Dipietro, L., Caspersen, C. J., Ostfeld, A. M., & Nadel, E. R. (1993). A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 25(5), 628-642. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199305000-00016

Donahue, L. (2009). A pod design for nursing assignments: Eliminating unnecessary steps and increasing patient satisfaction by reconfiguring care assignments. American Journal of Nursing, 109(11 Suppl), 38-40. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000362019.47504.9d

Edwards, D., & Burnard, P. (2003). A systematic review of stress and stress management interventions for mental health nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42(2), 169-200. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02600.x

Forman-Hoffman, V., Little, A., & Wahls, T. (2006). Barriers to obesity management: A pilot study of primary care clinicians. BMC Family Practice, 7, 35. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-7-35

Gabrielle, S., Jackson, D., & Mannix, J. (2008). Adjusting to personal and organisational change: Views and experiences of female nurses aged 40-60 years. Collegian, 15(3), 85-91. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2007.09.001

Gambino, K. M. (2010). Motivation for entry, occupational commitment and intent to remain: A survey regarding registered nurse retention. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(11), 2532-2541. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05426.x

Hasson, R. E., Haller, J., Pober, D. M., Staudenmayer, J., & Freedson, P. S. (2009). Validity of the Omron HJ-112 pedometer during treadmill walking. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 41(4), 805-809. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818d9fc2

HBO Documentary Films. (2012). The Weight of the Nation. Retrieved from http://theweightofthenation.hbo.com/

Holbrook, E. A., Barreira, T. V., & Kang, M. (2009). Validity and reliability of Omron pedometers for prescribed and self-paced walking. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 41(3), 670-674. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181886095

Hu, L., Motl, R. W., McAuley, E., & Konopack, J. F. (2007). Effects of self-efficacy on physical activity enjoyment in college-aged women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 14(2), 92-96.

Hunskaar, S. (2008). A systematic review of overweight and obesity as risk factors and targets for clinical intervention for urinary incontinence in women. Neurourology & Urodynamics, 27(8), 749-757. doi: 10.1002/nau.20635

Institute of Medicine. (2010a). Bridging the evidence gap in obesity prevention: A framework to inform decision making. Washington, DC National Academy of Sciences.

Institute of Medicine. (2010b). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2012). Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: Solving the weight of the nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Keller, S. M. (2009). Effects of extended work shifts and shift work on patient safety, productivity, and employee health. American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal, 57(12), 497-502; quiz 503-494. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20091124-05

King, K. A., Vidourek, R., & Schwiebert, M. (2009). Disordered eating and job stress among nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(7), 861-869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.00969.x

Kiresuk, T. J., & Sherman, R. E. (1968). Goal attainment scaling: A general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Mental Health Journal, 4(6), 443-453. doi: 10.1007/BF01530764

Lamond, N., Dorrian, J., Roach, G., McCulloch, K., Holmes, A., Burgess, H., … Dawson, D. (2003). The impact of a week of simulated night work on sleep, circadian phase, and performance. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(11), e13. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.11.e13

Lombard, C. B., Deeks, A. A., & Teede, H. J. (2009). A systematic review of interventions aimed at the prevention of weight gain in adults. Public Health Nutrition, 12(11), 2236-2246. doi:10.1017/S1368980009990577

McVicar, A. (2003). Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(6), 633-642. doi:10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02853.x

Miller, S. K., Alpert, P. T., & Cross, C. L. (2008). Overweight and obesity in nurses, advanced practice nurses, and nurse educators. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 2(5), 259-265. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00319.x

Mimura, C., & Griffiths, P. (2003). The effectiveness of current approaches to workplace stress management in the nursing profession: An evidence based literature review. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 60(1), 10-15. doi:10.1136/oem.60.1.10

Montalvo, I. (2007). The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators® (NDNQI®). Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 12(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol12No03Man02

Montgomery, K. L., & Geiger-Brown, J. (2010). Is it time to pull the plug on 12-hour shifts? Journal of Nursing Administration, 40(4), 147-149. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181d40e63

Morey, M. C., Snyder, D. C., Sloane, R., Cohen, H. J., Peterson, B., Hartman, T. J., … Demark-Wahnefried, W. (2009). Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(18), 1883-1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643

Muecke, S. (2005). Effects of rotating night shifts: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nuring, 50(4), 433-439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03409.x

Nadas, J., Putz, Z., Kolev, G., Nagy, S., & Jermendy, G. (2008). Intraobserver and interobserver variability of measuring waist circumference. Medical Science Monitor, 14(1), 15-18.

Nahm, E.-S., Barker, B., Resnick, B., Covington, B., Magaziner, J., & Brennan, P. F. (2010). Effects of a social cognitive theory-based hip fracture prevention web site for older adults. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 28(6), 371-379. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181f69d73

Nahm, E.-S., Resnick, B., Bellantoni, M., Zhu, S., Brown, C., Brennan, P. F., (In Press). Dissemination of Theory-Based Online Bone Health Programs: Two Intervention Approaches. Health Informatics Journal.

Nahm, E.-S., & Warren, J. (2010, September). Testing the feasibility of Wii exercise programs for nurses: Pilot study. Paper presented at the Franklin Square Hospital Center EBP Council Research Meeting.

Nahm, E.-S., Warren, J., Zhu, S., An, M.-J., & Brown, J. (2012). Nurses’ self-care behaviors related to weight and stress. Nursing Outlook, 60(5), e23-e31. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2012.04.005

National Center for Health Statistics. (2009). Health, United States, 2009 with special feature on medical technology. Hyattsville, MD: Author. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus09.pdf

National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI). (2010). National database of nursing quality indicators. Retrieved from https://www.nursingquality.org/

National Institutes of Health. (2009). PAR-10-038: Dissemination and implementation research in health (R01). Retrieved from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-07-086.html#SectionI

National Institutes of Health. (2012). About NIH obesity research. Retrieved from http://www.obesityresearch.nih.gov/about/about.aspx

Nintendo. (2010). Wii. Available: http://wii.com/Nintendo. (2007). Wii sports. Retrieved from: http://www.nintendo.com/games/detail/1OTtO06SP7M52gi5m8pD6CnahbW8CzxE

Pescatello, L., DiPietro, L., Fargo, A., Ostfeld, A., & Nadel, E. (1994). The impact of physical activity and physical fitness on health indicators among older adults. Journal of Aging Physical Activity, 2(1), 2-13.

Qin, L., Knol, M. J., Corpeleijn, E., & Stolk, R. P. (2010). Does physical activity modify the risk of obesity for type 2 diabetes: A review of epidemiological data. European Journal of Epidemiology, 25(1), 5-12. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9395-y

Raingruber, B., & Robinson, C. (2007). The effectiveness of Tai Chi, yoga, meditation, and Reiki healing sessions in promoting health and enhancing problem solving abilities of registered nurses. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28(10), 1141-1155. doi: 10.1080/01612840701581255

Ressler, P. K. (2007). Stress management for nurses. Beginnings, 27(1), 14-15.

Rhodes, R. E., Fiala, B., & Conner, M. (2009). A review and meta-analysis of affective judgments and physical activity in adult populations. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38(3), 180-204. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9147-y

Rhodes, R. E., Warburton, D. E., & Murray, H. (2009). Characteristics of physical activity guidelines and their effect on adherence: A review of randomized trials. Sports Medicine, 39(5), 355-375. doi: 00007256-200939050-00003

Ruotsalainen, J., Serra, C., Marine, A., & Verbeek, J. (2008). Systematic review of interventions for reducing occupational stress in health care workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 34(3), 169-178. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1240

Schulte, P. A., Wagner, G. R., Ostry, A., Blanciforti, L. A., Cutlip, R. G., Krajnak, K. M., … Miller, D. B. (2007). Work, obesity, and occupational safety and health. American Journal of Public Health, 97(3), 428-436. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086900

Shaikh, A. R., Yaroch, A. L., Nebeling, L., Yeh, M. C., & Resnicow, K. (2008). Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adults a review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34(6), 535-543. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.028

Shneiderman, B. (2002). Leonardo's laptop: Human needs and the new computing technologies. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sodlerlund, A., Fischer, A., & Johansson, T. (2009). Physical activity, diet and behaviour modification in the treatment of overweight and obese adults: A systematic review. Perspectives in Public Health, 129(3), 132-142. doi: 10.1177/1757913908094805

SureSource LLC. (2010). GOsmart™ pocket pedometer. Retrieved from http://omronhealthcare.com/wp-content/uploads/HJ112_IM_10262010.pdf

Sveinsdottir, H., & Gunnarsdottir, H. K. (2008). Predictors of self-assessed physical and mental health of Icelandic nurses: Results from a national survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(10), 1479-1489. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.01.007

Tanne, J. H. (2010). Michelle Obama launches programme to combat US childhood obesity. British Medicine Journal, 340, c948. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c948

Thomas, S., Reading, J., & Shephard, R. J. (1992). Revision of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Canadian Journal of Sport Sciences, 17(4), 338-345.

Thompson, C. E., & Wankel, L. M. (2006). The effects of perceived activity choice upon frequency of exercise behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 10(5), 436-443.

Trinkoff, A. M., Geiger-Brown, J., Brady, B., Lipscomb, J., & Muntaner, C. (2006). How long and how much are nurses now working? American Journal of Nursing, 106(4), 60-71, quiz 72. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200604000-00030

Tsai, A. G., Williamson, D. F., & Glick, H. A. (2011). Direct medical cost of overweight and obesity in the USA: A quantitative systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 12(1), 50-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00708.x

Twigg, D., Duffield, C., Thompson, P. L., & Rapley, P. (2010). The impact of nurses on patient morbidity and mortality - The need for a policy change in response to the nursing shortage. Australian Health Review, 34(3), 312-316. doi: 10.1071/AH08668

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2010). 2010-2011 editions of the occupational outlook handbook and the career guide to industries available on the internet [Press release]. Retrieved from www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/ooh_12172009.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Health Resources and Services Administration. (2010). The registered nurse population: Initial findings from the 2008 National sample survey of registered nurses. Retrieved from http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/rnsurveys/rnsurveyfinal.pdf

Usability Professionals' Association. (2010). What is user-centered design? Retrieved from www.upassoc.org/usability_resources/about_usability/what_is_ucd.html

Welton, J. M., Decker, M., Adam, J., & Zone-Smith, L. (2006). How far do nurses walk? Medsurg Nursing, 15(4), 213-216.

Yuan, S., Chou, M., Hwu, L., Chang, Y., Hsu, W., & Kuo, H. (2009). An intervention program to promote health-related physical fitness in nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(10), 1404-1411. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02699.x

Zapka, J. M., Lemon, S. C., Magner, R. P., & Hale, J. (2009). Lifestyle behaviours and weight among hospital-based nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(7), 853-860. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00923.x

Zitkus, B. S. (2011). The relationship among registered nurses' weight status, weight loss regimens, and successful or unsuccessful weight loss. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 23(2), 110-116. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00583.x