Nursing burnout is a common and costly organizational problem that affects both nurses and patient care. Health behaviors, such as healthy nutrition, and adequate sleep and exercise, have been cited as burnout reduction strategies. At Mayo Clinic, the authors developed an educational program for nurses and other healthcare team members to address burnout and consider strategies to navigate work and life stressors. Audience participation software measured the percentage of audience members meeting criteria for burnout, as well as confidence in their ability to manage three basic health-influencing behaviors that included eating, sleeping, and moving well. Findings revealed a high prevalence of nursing burnout and low confidence in achieving healthy nutrition, sleep, and exercise. In this article the authors review selected background information about self–care, describe the course design and implementation of an educational program, and discuss findings from a brief survey included in the program. Their discussion considers their findings in relation to select literature and identifies needs for further inquiry and project limitations. They conclude by encouraging the profession of nursing and nurses to continue efforts to support self-care through healthy behaviors throughout their careers.

Key Words: Nurses, burnout, nutrition, sleep, exercise, stress, work, demand, control, support, self-care.

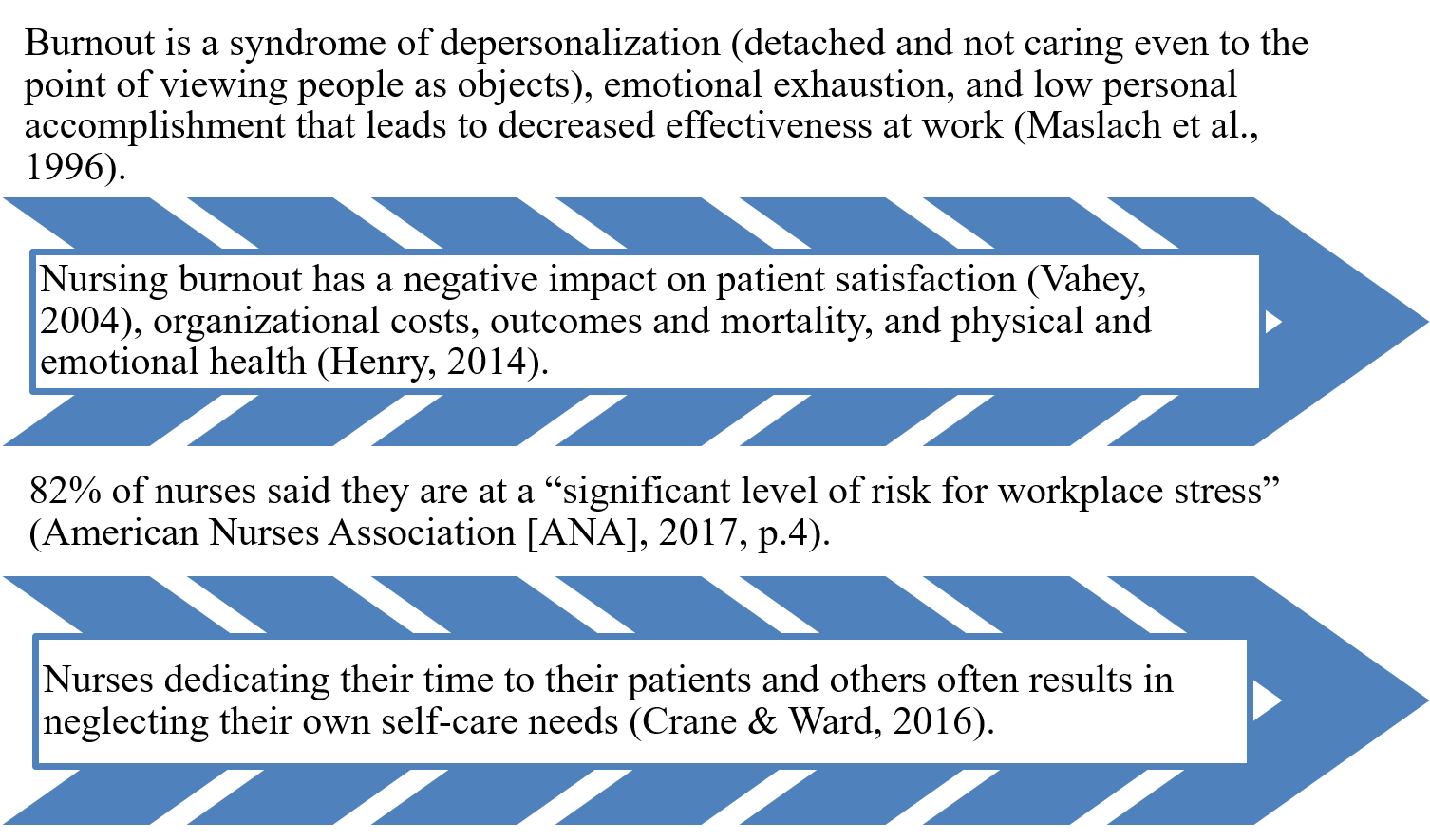

Burnout has become a topic of significance in healthcare, particularly in nursing.Burnout has become a topic of significance in healthcare, particularly in nursing (see Figure 1). The high demands placed on the inter-professional healthcare team have led to significant burnout amongst these team members (Bridgeman et al., 2018). Burnout has become increasingly prevalent (Shanafelt et al., 2015), and has been linked to medical errors and patient safety issues (Bridgeman et al., 2018; Hall et al., 2016). Specifically, nurses experiencing burnout often neglect the basic self-care behaviors of eating, sleeping, and moving well, which in turn compounds symptoms of burnout (Ross et al., 2017).

...nurses experiencing burnout often neglect the basic self-care behaviors of eating, sleeping, and moving well...In this article, we review selected background information about self–care, and describe the course design and implementation of an educational program developed and implemented at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. We will discuss our findings from a brief survey included in the program to inform our continued dedicated efforts to this important concern for nurses and all healthcare providers. Our discussion considers these findings in relation to select literature and identifies needs for further inquiry.

Figure 1. Nursing Burnout Facts and Figures

Background

In 2014, OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing (OJIN) posted the topic: “Healthy Nurses: Perspectives on Caring for Ourselves,” (Topic # 55). A number of authors focused on topics related to self-care strategies for nurses. Letvak introduced this topic, explaining it had been “designed to develop 'healthy nurses’ who are physically and emotionally prepared to provide the best possible care to our patients” (Letvak, 2014, para. 13). Contributing authors discussed interpersonal relationships and the importance of effective interpersonal communication strategies (Vertino, 2014); the complex dynamic between social media and the health of individual nurses and their workplaces (Jackson et al., 2014); and a structured course for nursing self-care (Blum, 2014). Other articles described a participant-centered, weight-management program (Nahm et al., 2014), and factors related to healthy diet and physical activity, noting that over 50% of nurses had moderately healthy diets but were insufficiently active (Albert et al., 2014). Speroni (2014) reviewed the paucity of evidence-based workplace wellness programs focused on healthy weight and offered suggestions for organizations interested in designing internal programs. Reed (2014) discussed the importance of good nutrition to reduce the impact of stressors and positively influence health and mentioned that quality sleep and exercise contributed to personal health.

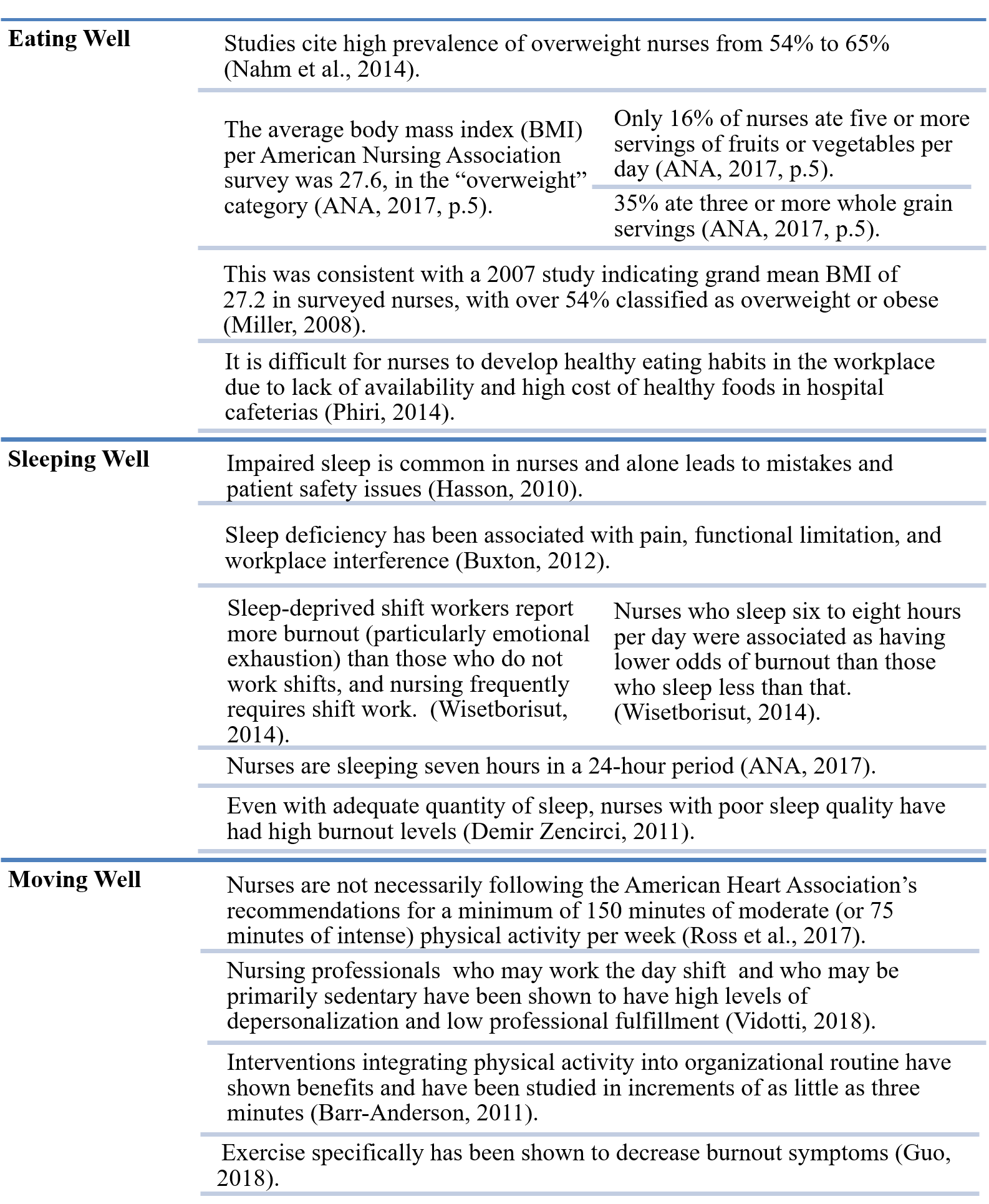

...having knowledge of healthy behaviors does not necessarily translate into lifestyle changes for nurses.Eating, Sleeping, and Moving Well in Nurses

Selected topics, including eating, sleeping, and moving well in nurses, were addressed in the OJIN topic described above and in other publications (see Figure 2, developed by author Couser). Nurses are well educated professionals who understand and teach patients about health-promoting behaviors, such as good nutrition, sleep, and exercise. However, having knowledge of healthy behaviors does not necessarily translate into lifestyle changes for nurses (Albert et al., 2014; Malik et al., 2011).

Figure 2. Eating, Sleeping, and Moving Well in Nurses

Including Nurses in the Solution

...during the time burnout had been studied this closely, there were few concrete interventions to address the problem.Since 2016, discussions about burnout have become increasingly important at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Institutionally there has been a rigorous focus on physician burnout (e.g., extensive research conducted by Dr. Tait Shanfelt and colleagues and physician engagement groups) and burnout in general (e.g., Employee Assistance Program counselors; other offerings through the separate employee healthy living center). However, during the time burnout had been studied this closely, there were few concrete interventions to address the problem. Meanwhile, with a work force of close to 35,000 employees in Rochester, comprised of thousands of nurses, the nurses at Mayo Clinic were seeking solutions and options. Anecdotally, both in discussions with nursing leadership and in counseling of individual nurses, Employee Assistance Program professionals reported large numbers of nurses in distress.

It was generally recognized that a lack of engagement in self-care activities contributed to this burnout. To meet the gap of possible available solutions to address burnout, and increase the scope of availability to include nurses and others, we developed an educational course regarding burnout for employees of the Mayo Clinic. The course content was designed to address health behaviors that are a challenge for nurses and everyone. We conceptualized the course as an opportunity to support and validate nurses and other providers in their personal quest to identify sources of burnout and to guide them in navigating self-care activities, including eating, sleeping, and moving well.

Course Design and Implementation

It was generally recognized that a lack of engagement in self-care activities contributed to this burnout.At Mayo Clinic’s campus in Rochester, Minnesota, this “Optimizing Provider Potential” course was developed in an effort to provide an opportunity for nurses and other clinicians to discuss various topics related to healthy behaviors and to share ideas to manage stress and burnout. The course design was underpinned by the tenets of adult learning theory (Knowles, 1975) and social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977; Kay & Kibble, 2016). In the planning stages, we desired an interactive course that would immerse participants in this learning experience. We recognized that participants would need explanations of why the material was being taught (Knowles, 1975).

Much of the didactic material would likely be familiar, as healthcare providers are well educated and often teach this exact information to others. We also incorporated a self-directed approach so participants could tailor the material to their individual needs (Knowles, 1975). The interactive aspect of course was informed by social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977; Kay & Kibble, 2016); participants learned from and supported one another.

We also incorporated a self-directed approach so participants could tailor the material to their individual needs.The initial teaching challenge was holding audience attention. We addressed this challenge by keeping lectures to a minimum and enhancing the participatory experience. The plan included a facilitator to introduce basic concepts and reinforce the learning using easy-to-remember superhero metaphors for our modules, a strategy that would also help to reduce stigma. These metaphors, presented in five modules over a half day period of time (4 hours), are described in Table 1.

Table 1. Optimizing Provider Potential Course Structure

|

Superhero Modules |

Module Description |

|

Invincibility |

Protect health by appraising habits related to diet, exercise, sleep, and seeking help. Assess aspects of life's demands and identify which aspects can be controlled. |

|

Secret Identity |

Examine issues related to competing values and identify how competing values influence choices of where we ultimately put our efforts. |

|

Mental Projection |

Examine one's future life in the ideal, in relationship to what one is ultimately seeking for his/her reward. |

|

Shapeshifting |

Adapt goals and plans based upon the moving target of what is desired both from one's work and from one's life |

|

Super Allies |

Employ support to enhance one's individual strengths and to accomplish more by working as teams. |

During the course, participants were challenged to reflect on their lives and potential positive changes. The facilitator, a psychiatrist, posed questions to the audience to spark discussion; encourage brainstorming for individual reflection; and promote writing in personal course booklets. Through effective facilitation and active discussion, participants learned from each other, and collected ideas to tackle challenging behaviors.

Participants were encouraged to experiment with their goals after completing the course...Participants were encouraged to experiment with their goals after completing the course and to continually revise these goals based upon what they had learned. This was an important point as the intention of the course was to provide self-help principles so that participants could continue to experiment on their own after the course ended. Although the course initially was not designed with follow-up in mind, follow-up will be considered in the future, based on feedback from course participants.

The course was offered six times to live audiences of providers between May 2017 and July 2018. Select details about course content and approaches are listed in Table 2. Of the six sessions offered to various participants, all except Session 3 were offered primarily to nurses. Session 3 was offered to 24 participants, all of whom were physicians (MD/DO), physician assistants (PA), or advanced practice registered nurses (APRN).

Table 2. Optimizing Teaching Effectiveness Course Content

|

Point |

Explanation |

|

Advertising |

The course was advertised via internal e-mails to Mayo Clinic employees. and through the Intranet. All sessions (except session 3) were advertised specifically to nurses; however, the first two sessions may have included at least one, but not more than three, non-nursing participants. Session 3 was advertised as part of a larger continuing medical education course, specifically to internal and external physicians, physician assistants, and advanced practice nurses. As initial course offerings applied primarily to nurses, sessions 4, 5 and 6 were advertised to nurses only. |

|

Demographic information |

Specifics were not collected. However, participant roles were determined by their credentials when registering for the course. |

|

Course session composition |

The following 6 course sessions were comprised of the following participants: 1) 24 participants, primarily nurses (i.e., at most three were not nurses) |

|

Questions posed to audience that are considered in Results |

1) I have been feeling burned out (i.e., experiencing at least one of the following: depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, or low personal accomplishment). A. True 2) I do a good job with eating right. A. Strongly agree. 3) I do a good job with getting enough sleep. A. Strongly agree. 4) I do a good job with exercising. A. Strongly agree. |

Participants volunteered to take the course and attended a session on their specified day. Each participant received a booklet of educational material that also served as a source of journaling during the offering. The facilitator provided didactic material and led discussions. A psychiatrist (the facilitator) moderated the discussion by posing the questions and allowing audience members to respond aloud. Concurrently participants made personal notes about their own specific situation.

Participants were assigned participation software, specifically an electronic transmitter, to allow anonymous answers to questions posed. Many questions utilized participation software. For questions posed by audience participation software, the facilitator presented the slide with the question and allowed a short time for audience members to answer before moving on to the next slide. Not all participants responded to each question as responses were anonymous and voluntary.

Between 44 and 46 questions were asked by audience participation software at each educational session; all questions were multiple choice or true/false types of questions. Approval to acquire and publish unidentifiable data from this event was retrospectively obtained from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board without concern, due to the minimal risk of the intervention. We consider four relevant questions only (see Table 2) in our discussion of the results. These questions were asked consistently (i.e., the question was asked verbatim in the same way at each session). The survey questions were instructor-developed and no reliability or validity data is yet available.

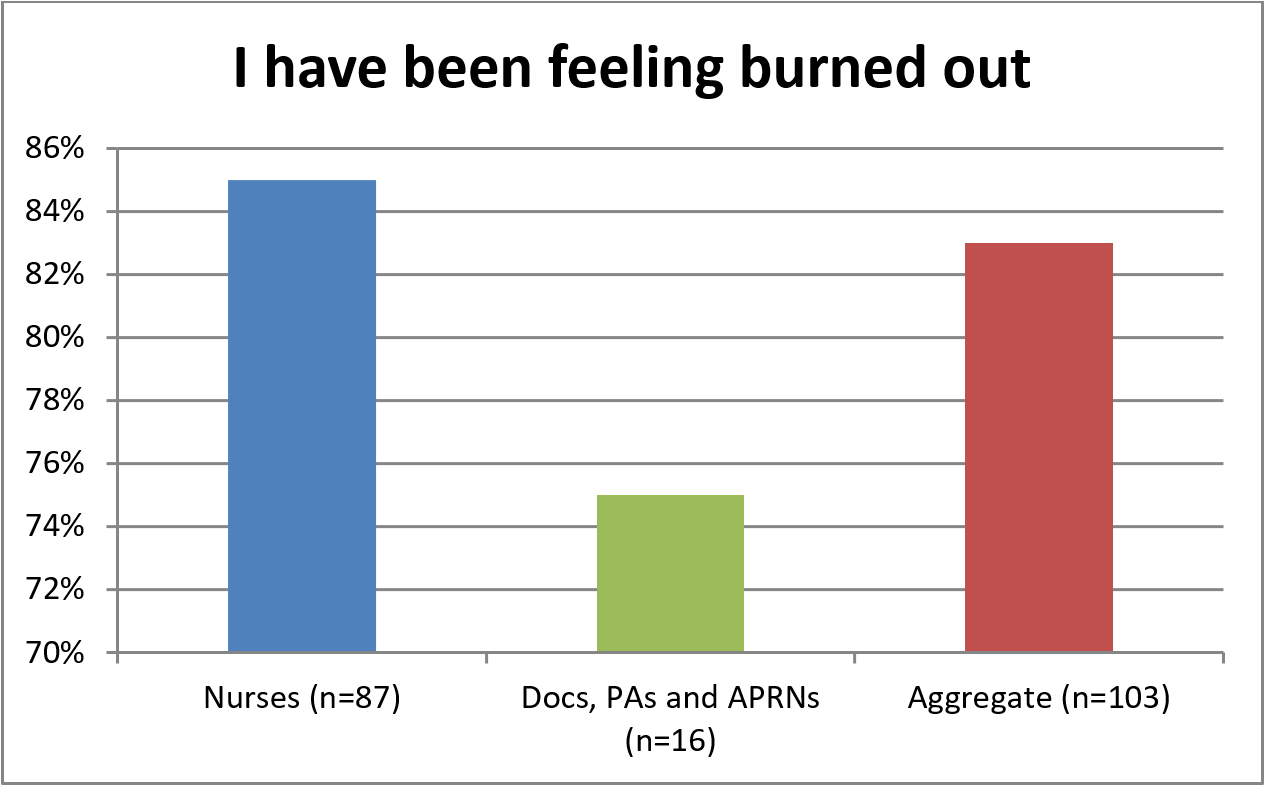

Findings Related to the Optimizing Provider Potential Course

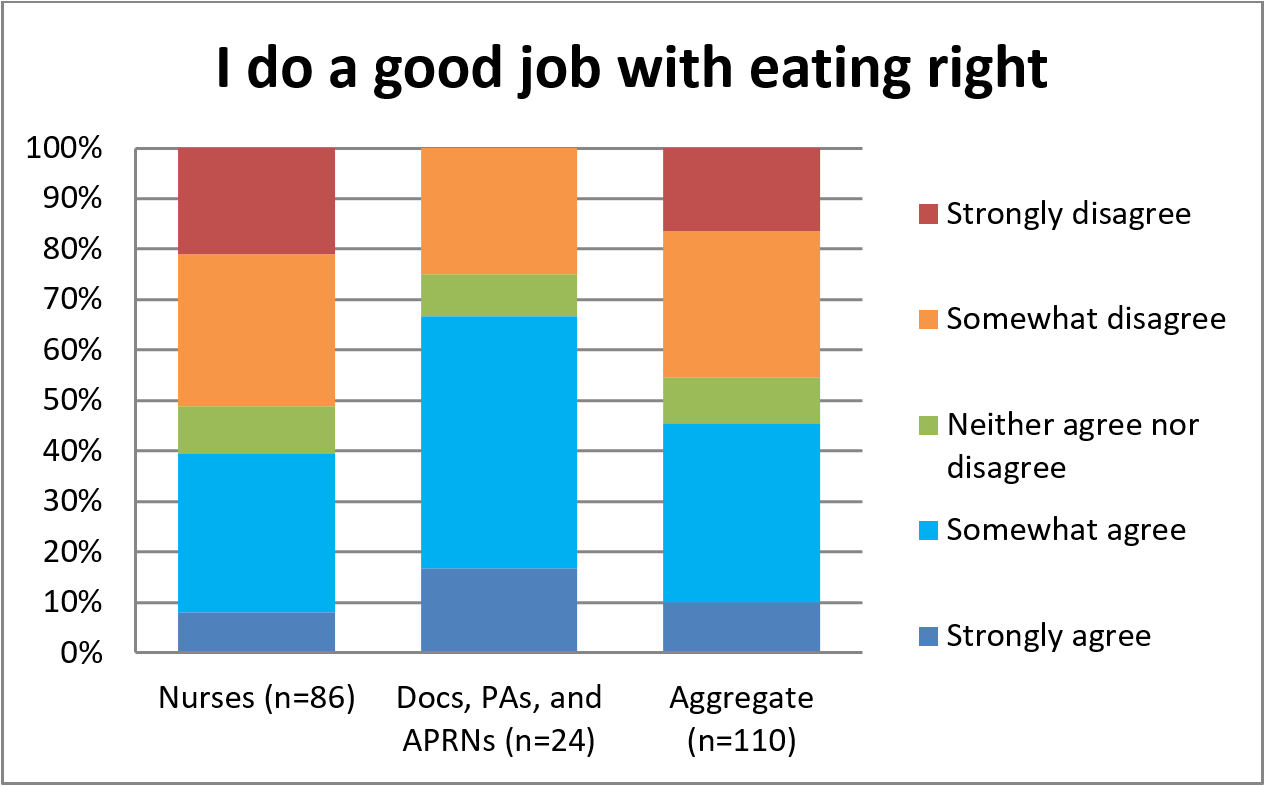

Aggregate results are shown in Table 3. Although there were 134 participants over the six sessions, not all participants answered every question, thus the numbers do not add up to the total number of participants. Raw data and totals over all sessions are shown for each question. In aggregate, 83% of participants indicated burnout; 45% at least somewhat disagreed that they were doing a good job with eating right; 50% at least somewhat disagreed that they were doing a good job with getting enough sleep; and 58% at least somewhat disagreed that they were doing a good job with exercising.

Table 3. Aggregate Results from “Optimizing Provider Potential” Sessions

|

Session Date |

5/15/ 2017 |

8/28/ 2017 |

10/26/ 2017 |

2/5/ 2018 |

7/16/ 2018 |

11/26/ 2018 |

Total Number of Participants |

|

|

Session |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

||

|

Number of Participants |

n=24 |

n=22 |

n=24 |

n=15 |

n=12 |

n=37 |

n=134 |

|

|

Professional Status |

Mostly nurses |

Mostly nurses |

MD/ DO/PA/ APRNs |

All nurses |

All nurses |

All nurses |

||

|

Question 1. I have been feeling burned out (i.e., at least one of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, or low personal accomplishment) (True / False) |

||||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

All Sessions |

Percentage |

|

True |

17 |

17 |

12 |

9 |

6 |

25 |

86 |

83% |

|

False |

3 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

17 |

17% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

20 |

20 |

16 |

11 |

7 |

29 |

103 |

100% |

|

2. I do a good job with eating right. (Multiple Choice) |

||||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

All Sessions |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

1 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

11 |

10% |

|

Somewhat agree |

8 |

4 |

12 |

4 |

1 |

10 |

39 |

35% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

10 |

9% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

7 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

3 |

11 |

32 |

29% |

|

Strongly disagree |

5 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

18 |

16% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

22 |

16 |

24 |

9 |

8 |

31 |

110 |

100% |

|

3. I do a good job with getting enough sleep. (Multiple Choice) |

||||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

All Sessions |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

3 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

18 |

15% |

|

Somewhat agree |

7 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

0 |

11 |

34 |

28% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

7% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

8 |

4 |

7 |

4 |

3 |

8 |

34 |

28% |

|

Strongly disagree |

3 |

6 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

26 |

22% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

23 |

20 |

24 |

12 |

8 |

33 |

120 |

100% |

|

4. I do a good job with exercising. (Multiple Choice) |

||||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

All Sessions |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

4 |

3 |

7 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

16 |

14% |

|

Somewhat agree |

2 |

5 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

22 |

19% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

10 |

9% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

4 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

17 |

15% |

|

Strongly disagree |

12 |

9 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

17 |

50 |

43% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

23 |

20 |

22 |

10 |

7 |

33 |

115 |

100% |

Session 3 was comprised primarily of physicians, physician assistants, and advanced practice nurses. Table 4 includes the results from session 3 only. Of those participants, 75% indicated burnout; 25% at least somewhat disagreed to doing a good job with eating right; 50% at least somewhat disagreed to doing a good job with getting enough sleep; and 32% at least somewhat disagreed to doing a good job with exercising.

Table 4. Results from Course Session 3

|

Session Date |

10/26/2017 |

|

|

Session |

3 |

|

|

Number of Participants |

n=24 |

|

|

Professional Status |

MD/DO/PA/APRNs |

|

|

Question 1. I have been feeling burned out (i.e., at least one of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, or low personal accomplishment) (True / False) |

||

|

|

3 |

Percentage |

|

True |

12 |

75% |

|

False |

4 |

25% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

16 |

100% |

|

|

|

|

|

2. I do a good job with eating right. (Multiple Choice) |

||

|

|

3 |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

4 |

17% |

|

Somewhat agree |

12 |

50% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

2 |

8% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

6 |

25% |

|

Strongly disagree |

0 |

0% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

24 |

100% |

|

3. I do a good job with getting enough sleep. (Multiple Choice) |

||

|

|

3 |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

6 |

25% |

|

Somewhat agree |

6 |

25% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

0 |

0% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

7 |

29% |

|

Strongly disagree |

5 |

21% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

24 |

100% |

|

4. I do a good job with exercising. (Multiple Choice) |

||

|

|

3 |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

7 |

32% |

|

Somewhat agree |

6 |

27% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

2 |

9% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

2 |

9% |

|

Strongly disagree |

5 |

23% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

22 |

100% |

All other sessions were composed primarily of nurses, the results of which are shown in Table 5. Of nursing participants, 85% indicated burnout. Thirty-nine percent at least somewhat agreed and 51% at least somewhat disagreed to doing a good job with eating right. Forty-two percent at least somewhat agreed and 50% at least somewhat disagreed to doing a good job with getting enough sleep. Twenty-seven percent at least somewhat agreed and 64% at least somewhat disagreed to doing a good job with exercising.

Table 5. Results from “Optimizing Provider Potential” Sessions with Nursing Participants

|

Session Date |

5/15/ 2017 |

8/28/ 2017 |

2/5/ 2018 |

7/26/ 2018 |

11/26/ 2018 |

Total Number of Participants |

|

|

Session |

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

||

|

Number of Participants |

n=24 |

n=22 |

n=15 |

n=12 |

n=37 |

n=110 |

|

|

Professional Status |

Mostly nurses |

Mostly nurses |

All nurses |

All nurses |

All nurses |

||

|

Question 1. I have been feeling burned out (i.e., at least one of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, or low personal accomplishment) (True / False) |

|||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

All |

Percentage |

|

True |

17 |

17 |

9 |

6 |

25 |

74 |

85% |

|

False |

3 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

13 |

15% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

20 |

20 |

11 |

7 |

29 |

87 |

100% |

|

2. I do a good job with eating right. (Multiple Choice) |

|||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

All |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

7 |

8% |

|

Somewhat agree |

8 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

10 |

27 |

31% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

1 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

8 |

9% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

7 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

11 |

26 |

30% |

|

Strongly disagree |

5 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

18 |

21% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

22 |

16 |

9 |

8 |

31 |

86 |

100% |

|

3. I do a good job with getting enough sleep. (Multiple Choice) |

|||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

All |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

12 |

13% |

|

Somewhat agree |

7 |

6 |

4 |

0 |

11 |

28 |

29% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

8% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

8 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

8 |

27 |

28% |

|

Strongly disagree |

3 |

6 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

21 |

22% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

23 |

20 |

12 |

8 |

33 |

96 |

100% |

|

4. I do a good job with exercising. (Multiple Choice) |

|||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

All |

Percentage |

|

Strongly agree |

4 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

9 |

10% |

|

Somewhat agree |

2 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

16 |

17% |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

8 |

9% |

|

Somewhat disagree |

4 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

15 |

16% |

|

Strongly disagree |

12 |

9 |

3 |

4 |

17 |

45 |

48% |

|

Total Number of Responses |

23 |

20 |

10 |

7 |

33 |

93 |

100% |

There are some notable differences when comparing the “nurses only” data to Session 3 participants. Figure 3 illustrates that while 85% of nurses surveyed indicated burnout, only 75% of the other providers did.

Figure 3. Burnout Measured in Course Audience

Nurses were less confident in their ability to eat right. Figure 4 illustrates that only 39% of nurses indicated they agreed at least somewhat to doing a good job with eating right versus 67% of the other providers.

Figure 4. Confidence with Eating Right

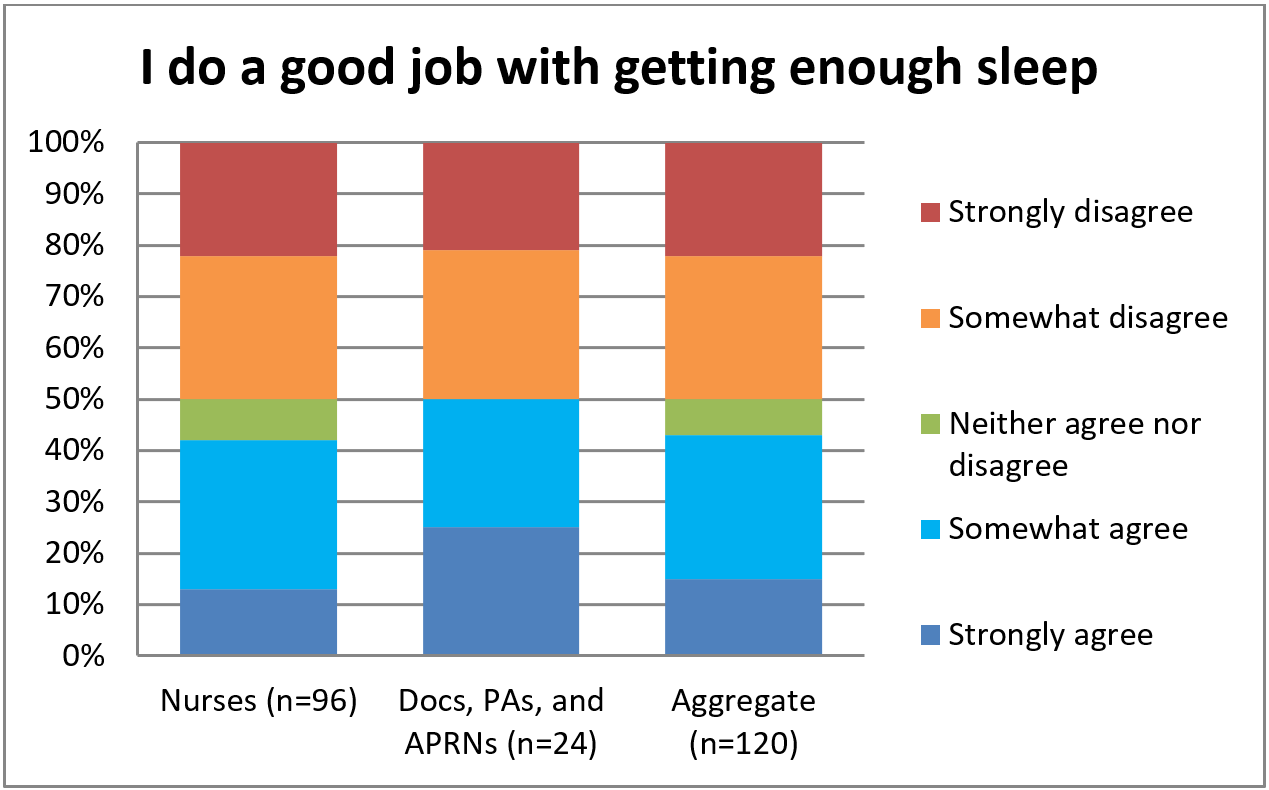

Nurses shared about the same level of confidence with other providers regarding doing a good job with getting enough sleep. Figure 5 shows that about half of nurses and half of other providers at least somewhat agreeing/disagreeing to getting enough sleep.

Figure 5. Confidence with Getting Enough Sleep

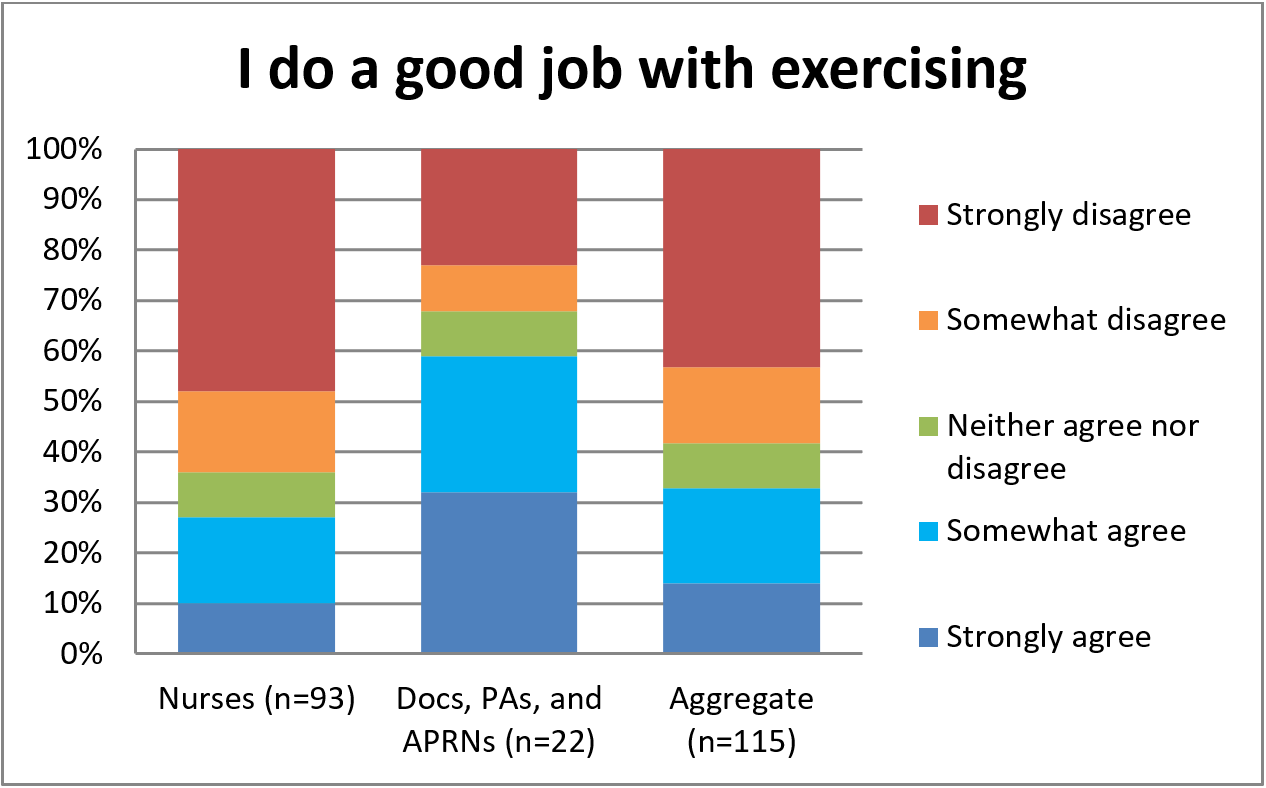

Again nurses were less confident than other providers in their ability to do a good job with exercising. Per Figure 6, only 27% of nurses at least somewhat agreed to doing a good job of exercising compared to 59% of the other providers.

Figure 6. Confidence with Exercising

Discussion

This survey provided data regarding burnout and self-perception of simple health behaviors. This particular group indicated higher levels of burnout than is described in the literature, with 85% of the group of primarily nurses indicating burnout. This is contrasted with the relatively lower (but still high) 75% of physicians, physician assistants, and advanced practice nurses who indicated burnout. The higher rates could be due to selection bias into the educational program (i.e., those who feel that they are burned out are more likely to seek solutions). Without knowing the exact composition of the audience or other factors, it is not appropriate to extrapolate further conclusions. However, the relatively higher rate of burnout in nurses versus physicians, physician assistants, and advanced practice nurses was an interesting finding, even in light of the small group of physicians, physician assistants, and advanced practice nurses.

The nurses surveyed did not seem satisfied with their health behaviors.The nurses surveyed did not seem satisfied with their health behaviors. Fifty-one percent of nurses at least somewhat disagreed that they were doing a good job with eating right; 50% at least somewhat disagreed related to getting enough sleep; and 64% at least somewhat disagreed related to exercising. Even though this survey had a low number of physicians, physician assistants, and advanced nurse practitioners, this smaller physician group (Session 3, n=24) generally had higher confidence in their health behaviors (i.e., as compared to nurses), at least regarding eating and exercise. For this physician group, 25% at least somewhat disagreed they were doing a good job with eating right, 50% at least somewhat disagreed they were doing a good job with getting enough sleep (same as in nursing group), and 32% at least somewhat disagreed they were doing a good job with exercising. Given this was a limited survey with a small sample and selection bias, no conclusions can be generalized. Yet, it is interesting to begin to compare confidence in healthy nutrition, sleep, and exercise behaviors found in nurses versus other colleagues.

Specifically regarding healthy nutrition, although 51% of nurses at least somewhat disagreed they were doing a good job with eating right, 39% of nurses at least somewhat agreed with this statement. The survey results were not compared to actual dietary habits. However, in Albert et al.’s (2014) study of 278 nurse participants, by self-assessment 66.3% of nurses had a moderately healthy diet, 16.7% had a mostly healthy diet and 17% had an unhealthy diet. In Albert’s same study group, the nurses indicated moderate confidence in maintaining a healthy weight or losing weight. Although it is not possible to make meaningful comparisons between the current survey and Albert’s study, the nurses in the current survey were generally less confident in their dietary habits.

For solutions regarding issues with nutrition, the author asked the nursing audience during the educational sessions for practical ideas regarding healthy behaviors. These practical tips are listed in Table 6. The “eating well” ideas suggested by these nursing audience members were similar to what Reed (2014) suggested in tips to avoid potential food pitfalls, including: commitment to health, planning and packing, drinking water, and allowing the occasional slight indulgence as a treat. The suggestions by this audience were geared toward reducing barriers and what individuals could control on their own. This underscores the point Albert and colleagues (2014) made that, of the factors associated with a healthy diet, perceiving fewer barriers was the most important. We agree with Albert and colleagues regarding the value of developing hospital programs that reduce barriers to healthy eating at work.

Table 6. Practical Tips from Nursing Peers Regarding Healthy Behaviors

|

Eating Well |

Always have a predetermined grocery list and stick to items on list to avoid impulse purchases |

|

Take notes in a simple "bullet journaling" format to see what works and what does not (allow notes to serve as a comparison point to scientifically iterate regarding dietary habits) |

|

|

Be mindful on eating by not "eating on the fly" but rather taking time to enjoy food on breaks off the nursing unit |

|

|

Place sticky notes around the house with positive quotes and reminders to support good nutrition |

|

|

Practice self-compassion and recognize there are seasons for everything (i.e., if healthy eating isn't working now, then maybe try again at a more opportune time) |

|

|

Practice good meal planning (e.g., plan meals for a week and do cooking in batches) |

|

|

Sleeping Well |

Focus on sleep hygiene by staying organized and setting aside specific sleep hours |

|

Create a soothing sleep environment by using enhancements, such as soft music, essential oils, and a dark environment free from distraction |

|

|

Use sleep apps to collect data to analyze for solutions |

|

|

Reduce electronic screen time to make it easier to "unplug" and fall asleep |

|

|

Moving Well |

Set aside specific time for exercise (particularly at a time of high energy for the individual) |

|

Practice self-compassion and forget about 'the perfect workout plan' |

|

|

Exercise whenever possible, with flexibility in scheduling and in smaller chunks |

|

|

Walk at work (e.g., during breaks, walking meetings, and with patients when possible and appropriate) |

|

|

Stress Reduction |

Minimize interruptions (e.g., reduce frequency of checking e-mail, turn off phone notifications) |

|

Make any team problems at work into a project others can help solve |

|

|

Take breaks away from the work unit |

|

|

Use work resources (e.g., exercise facilities, break rooms, and employee assistance programs) |

|

|

Maintain a positive attitude |

|

|

Focus on one thing at a time |

|

|

Delegate appropriately |

|

|

Know when to assertively and appropriately say no |

|

|

Ask for help when it is needed |

Barriers given by the nursing audience included rotating shifts, long hours, competing priorities at home, and a general theme of not enough time.Specifically regarding healthy sleep, 42% of nurses surveyed at least somewhat agreed they were doing a good job with getting enough sleep (versus 8% neutral and 50% at least somewhat disagreeing). Barriers given by the nursing audience included rotating shifts, long hours, competing priorities at home, and a general theme of not enough time. Numerous tips were given by the nursing audience, also listed in Table 6. Although Reed (2014) discussed sleep-related issues (e.g., poor sleep being associated with poor nutrition and exercise as a means to improve sleep quality), further study and discussion could be focused on nurse-specific solutions to healthy sleep.

Specifically regarding healthy exercise, only 27% of nurses at least somewhat agreed they were doing a good job with exercising. This is consistent with Albert et al.’s (2014) discussion suggesting weak self-efficacy that nurses could be physically active five days per week. This is also consistent with Nahm and colleagues’ (2012) preliminary study indicating that 71.9% of nurses reported lack of exercise. In the current survey, audience members gave ideas for moving well that are listed in Table 6. Although the current survey was focused on personal plans to combat burnout, the audience members also gave many tips for stress reduction in general (see Table 6).

Finding solutions to nursing burnout requires understanding models that explain burnout.Finding solutions to nursing burnout requires understanding models that explain burnout. One such model, the demand-control (-support) model, suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have (Karasek, 1979), and that social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain (Johnson, 1989). The 'demand' portion of this model has already been brought to light in previous writing. In discussing self-care for nurses, Blum (2014) outlined many occupational stressors for practicing nurses: protecting patients’ rights; autonomy and informed consent to treatment; staffing patterns; advanced care planning; surrogate decision-making; greater patient acuity; unpredictable and challenging workspaces; violence; increased paperwork; reduced managerial support; role-based factors (e.g., lack of power, role ambiguity, role conflict); and threats to career development and achievement (e.g., threat of redundancy, being undervalued, unclear promotion prospects). These stressors are very real demands on nurses that need to be better understood and managed to individualize nursing burnout solutions.

This greater sense of control and support could buffer against burnout.Nurse managers and individual nurses subjected to these demands can buffer them by paying attention to the 'control' and 'support' aspects of the demand-control(-support) model. For example, a nurse manager could empower a team of nurses to brainstorm solutions to a problem that the team identifies as both relevant and having potential 'low hanging fruit' solutions. Imagine that the nursing team wanted to tackle the problem of increased paperwork. If the nurse manager skillfully led the team to implement a feasible solution, this could allow both a sense of greater control among the group and a sense of cohesion. This greater sense of control and support could buffer against burnout.

Although successful teams can decrease burnout, the unfortunate reality is that non-cohesive teams and/or unskilled nurse managers can compound the problem. In these situations, individual nurses can feel demoralized and powerless. In the authors’ experience, these are times when self-care and appropriate help-seeking are crucial. Yet it can be a natural response to let self-care slide and not seek help when one is in survival mode and sees the problem created by an unforgiving work system and/or an unskilled manager. Thus, the invitation posed by Blum becomes paramount: “I challenge you to consider what you currently do to practice self-care behaviors. Are you satisfied with the results?” (Blum, 2014, para. 2).

...it can be a natural response to let self-care slide and not seek help when one is in survival mode...Overall, the concept of caring for ourselves is a complicated proposition. In the authors’ clinical experience in working with nurses, many by personality are hard on themselves and take care of others often at the expense of their own self-care. Most nurses seem to fully understand the 'oxygen mask' metaphor (i.e., on an airplane the flight attendant instructs you to put on your oxygen mask first before helping others) of taking care of their own needs so that they can more effectively take care of others. Yet, in the authors’ experiences, nurses are generally hardworking people, many with a 'pull yourself up by the bootstraps' mentality that leaves them thinking they are required to be invincible.

Overall, the concept of caring for ourselves is a complicated proposition.If nurses truly want to be invincible, it is imperative that they support and challenge each other to optimize well-being. As detailed in the Advisory Board report “Rebuild the Foundation for a Resilient Workforce” (Advisory Board, 2018), a key factor that undermines nurse resilience is that nurses today tend to feel “isolated in a crowd” (Advisory Board, 2018, p.5). Due to changes in care delivery, technology, responsibilities, and care protocols, nurses are more likely to feel insulated rather than part of a team. Therefore, nurse leaders are challenged to create a work community where individual nurses can connect with colleagues, identify barriers to health, and work through them together. This extra social and emotional support has the potential to lead to an environment where nurses can thrive (Advisory Board, 2018). Feedback from our Mayo Clinic “Optimizing Provider Potential” course indicates participants appreciated an environment that supported learning and sharing their anecdotes about adopting healthy behaviors. These healthy behaviors are the foundation for all nurses (and all people) to begin to achieve full potential and then work toward reaching their full potential.

Further Inquiry

Further study is needed regarding simple health behaviors in nurses (i.e., nutrition, sleep, and exercise) and their relationship to stress level and burnout. This is especially true as ineffective management of stress and burnout can prevent nurses from having rewarding careers and reaching their full potential. Specific areas for further study could include comparing nurses’ confidence in their health behaviors (e.g., healthy eating) to an actual measure of those behaviors (e.g., actual dietary measures), and also relating those measures to burnout.

New interventions that focus on team building and improving support are needed to buffer against burnout.The “Optimizing Provider Potential” course is an educational and interactive intervention that has been well-received. Areas of further inquiry may include measuring how this intervention and others actually impact health behaviors. New interventions that focus on team building and improving support are needed to buffer against burnout. Such interventions could be measured to determine whether they actually improve health behaviors, by employing a randomized, controlled trial design. Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1977; Kay & Kibble, 2016) can inform interventions for nurses to continue discussions about these issues, brainstorm new insights (e.g., through courses such as Optimizing Provider Potential), and motivate and support each other, thus innovating solutions to challenging health behaviors. New insights in turn could lead to current and effective long-term solutions to support rewarding nursing careers.

Limitations

The most significant limitation of this survey was the likelihood of selection bias. Participants were selected by advertising about potential burnout solutions. In addition, our data were collected from a relatively low sample size and participants came primarily from one institution. Therefore, these findings may not generalize to other nursing populations.

Conclusion

As nurses work to optimize their own self-care and navigate their career paths, they face inevitable challenges to their well-being, such as burnout. A culture of wellness goes beyond basic self-care activities to allow nurses to reach their full potential of health. This culture is inherent in the World Health Organization’s definition for mental health: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community" (World Health Organization, 2014, para.1).

A culture of wellness goes beyond basic self-care activities to allow nurses to reach their full potential of health.Nurses are motivated people with extensive healthcare knowledge; yet they need support to translate this information into action. As a profession, nursing leaders can help by continuing to develop programs specific to supporting healthy behaviors in the workforce, programs that then need to be studied and replicated. The components of the Mayo Clinic course “Optimizing Provider Potential” are relatively straightforward; similar courses/programs could be developed locally to engage nurses in peer support in their quest to optimize lifestyle changes.

Simple health behaviors regarding nutrition, sleep, and exercise are possibly more challenging for nurses even than their other health professional colleagues. Nurses are not invincible; like everyone else they are susceptible to the drain of daily stressors. A career in nursing, while rewarding, includes multiple demands placed upon nurses and often a lack of adequate control over these daily burdens. Many nurses tend to take on multiple roles and tasks, and commitment to simple health behaviors can become even more challenging. However, nurses can engage in self-care, and at least metaphorically approach an aura of invincibility, by reaffirming their individual commitments to the basic activities of healthy life, namely adequate nutrition, sleep, and exercise.

Authors

Greg Couser, MD, MPH

Email: couser.gregory@mayo.edu

Greg Couser is a consultant at Mayo Clinic both in the Division of Preventive, Occupational, and Aerospace Medicine, and in the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology. He studied industrial engineering prior to attending medical school. His subsequent formal residency training and board certification were in the areas of psychiatry and occupational medicine (a subspecialty of preventive medicine). Dr. Couser is a fellow both in the American Psychiatric Association and in the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. He has served for 14 years as Medical Director of the Mayo Clinic Rochester’s Employee Assistance Program, which provides counseling services and advice for over 35,000 employees, including nurses, allied health staff, and physicians. Dr. Couser's clinical practice has provided him with extensive experience in helping nurses navigate mental health issues, including burnout, in the workplace. He offers an educational course, “Optimizing Provider Potential,” to guide healthcare providers in developing solutions for their own self-care.

Sherry Chesak, PhD, RN

Email: chesak.sherry@may.edu

Sherry Chesak is a Nurse Scientist in the Department of Nursing, Division of Nursing Research, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota (MN). Her program of research is centered on care for the caregiver. She has focused primarily on studying stress management interventions to enhance resilience in both professional and family caregivers. Dr. Chesak received a Master’s degree in Nursing Education from Winona State University in Winona, MN, and a PhD in Nursing from the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee. Her doctoral dissertation focused on the Integration of a Stress Management and Resiliency Training in a Nurse Residency Program. She has attended multiple educational sessions which have prepared her to teach meditation and other stress management and resiliency principles. Her previous roles include Nursing Instructor, Nursing Education Specialist, and Midwest Program Director for Nursing Academic Affairs.

Susanne Cutshall, DNP, APRN, CNS, APHN-BC, HWNC-BC

Email: cutshall.susanne@may.edu

Susanne Cutshall is a certified adult health clinical nurse specialist with a specialty focus in integrative health. She has a post graduate certificate in complementary therapies and healing practices from the University of Minnesota and is certified as an advanced holistic nurse by the American Holistic Nurses Association. She has training in mind-body therapies, and several other modalities including acupressure, biofeedback, Reiki and Healing Touch. She is also trained as a whole health educator, and as a surgery coach, and is certified as a health and wellness coach. Susanne is currently working as an Integrative Health Specialist in the Department of General Internal Medicine in Rochester, MN, in the Complementary and Integrative Medicine Program. She has had the opportunity to conduct research and quality improvement programs that have been presented and published and include topics of massage therapy, acupuncture, ambient music, biofeedback, yoga, nurse stress and health behaviors, and resilience training with newly hired nurses. She is a worksite wellness champion for the Mayo Clinic Dan Abrahams Healthy Living Center work site wellness program and is active in the Department of Nursing at Mayo Clinic with their Wellness Champion Steering Group. She is an Assistant Professor of Nursing and Medicine with the Mayo College of Medicine. Dr. Cutshall is passionate about holistic nursing and integrative health practices and believes that these models of care can be instrumental in transforming our current healthcare trends.

References

Albert, N. M., Butler, R., & Sorrell, J. (2014). Factors related to healthy diet and physical activity in hospital-based clinical nurses. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 19(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No03Man05

Advisory Board. (2018). Rebuild the foundation for a resilient workforce: Best practices to repair the cracks in the care environment. https://www.advisory.com/-/media/Advisory-com/Research/NEC/White-Papers/2018/Rebuild%20the%20Foundation%20for%20a%20Resilient%20Workforce_aug-2018.pdf

American Nurses Association. (2017). Executive summary, American Nurses Association health risk appraisal. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/~495c56/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/healthy-nurse-healthy-nation/ana-healthriskappraisalsummary_2013-2016.pdf

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Blum, C. (2014). Practicing self-care for nurses: A nursing program initiative. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 19(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No03Man03

Barr-Anderson, D. J., AuYoung, M., Whitt-Glover, M. C., Glenn, B. A., & Yancey, A. K. (2011). Integration of short bouts of physical activity into organizational routine. A systematic review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(1), 76-93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.033

Bridgeman, P. J., Bridgeman, M. B., & Barone, J. (2018). Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. The Bulletin of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists, 75(3), 147-152. doi: 10.2146/ajhp170460

Buxton, O. M., Hopcia, K., Sembajwe, G., Porter, J. H., Dennerlein, J. T., Kenwood, C., Stoddard, A.M., Hashimoto, D., & Sorensen, G. (2012). Relationship of sleep deficiency to perceived pain and functional limitations in hospital patient care workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 54(7), 851-858. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31824e6913

Crane, P. J., & Ward, S. F. (2016). Self-healing and self-care for nurses. Association of Operating Room Nurses Journal, 104, 336-400. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2016.09.007

Demir Zencirci, A., & Arslan, S. (2011). Morning-evening type and burnout level as factors influencing sleep quality of shift nurses: A questionnaire study. Croatian Medical Journal, 52(4), 527-37. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2011.52.527

Guo, Y. F., Luo, Y. H., Lam, L., Cross, W., Plummer, V., & Zhang, J. P. (2018). Burnout and its association with resilience in nurses: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(1-2), 441-449. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13952

Hall, L. H., Johnson, J., Watt, I., Tsipa, A., & O’Connor, D. B. (2016). Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review. PloSOne, 11(7), e0159015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159015

Hasson, D., & Gustavsson, P. (2010). Declining sleep quality among nurses: A population-based four-year longitudinal study on the transition from nursing education to working life. PLoS One, 5(12), e14265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014265

Henry, B. J. (2014). Nursing burnout interventions: What is being done? Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18(2), 211-214. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.211-214

Jackson, J., Fraser, R., & Ash, P. (2014). Social media and nurses: Insights for promoting health for individual and professional use. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 19(3). doi: 0.3912/OJIN.Vol19No03Man02

Johnson, J. V. (1989). Collective control: Strategies for survival in the workplace. International Journal of Health Services, 19, 469-480. https://doi.org/10.2190/H1D1-AB94-JM7X-DDM4

Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285-308. doi: 10.2307/2392498

Kay, D., & Kibble, J. (2016). Learning theories 101: Application to everyday teaching and scholarship. Advances in Physiology Education, 40(1), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00132.2015

Knowles, M. S. (1975). The modern practice of adult education: Andragogy versus pedagogy. New York: Association Press.

Letvak, S. (2014). Healthy nurses: Perspectives on caring for ourselves. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 19(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No03ManOS

Malik, S., Blake, H., & Batt, M. (2011). How healthy are our nurses? New and registered nurses compared. British Journal of Nursing, 20(8), 489-496. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.8.489

Maslach, C., Jackson, S., & Leiter, M. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory manual (3rd Ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Miller, S. K., Alpert, P. T., & Cross, C. L. (2008). Overweight and obesity in nurses, advanced practice nurses, and nurse educators. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 2(5), 259-265. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00319.x

Nahm, E., Warren, J., Friedmann, E., Brown, J., Rouse, D., Park, B., & Quigley, K. (2014). Implementation of a participant-centered weight management program for older nurses: A feasibility study. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 19(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No03Man04

Nahm, E. S., Warren, J., Zhu, S., An, M. J., & Brown, J. (2012). Nurses’ self-care behaviors related to weight and stress. Nursing Outlook, 60(5), e23-e31. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2012.04.005

Phiri, L. P., Draper, C. E., Lambert, E. V., & Kolbe-Alexander, T. L. (2014). Nurses’ lifestyle behaviours, health priorities and barriers to living a healthy lifestyle: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Nursing, 13(38). doi: 10.1186/s12912-014-0038-6

Reed, D. (2014). Healthy eating for healthy nurses: Nutrition basics to promote health for nurses and patients. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 19(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No03Man07

Ross, A., Bevans, M., Brooks, A. T., Gibbons, S., Wallen, G. R. (2017). Nurses and Health-Promoting Behaviors: Knowledge May Not Translate into Self-Care. Association of Operating Room Nurses Journal, 105(3), 267-275. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2016.12.018

Shanafelt, T. D., Hasan, O., Dyrbye, L. N., Sinsky, C., Satele, D., Sloan, J., & West, C. P. (2015). Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(12), 1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

Speroni, K. (2014). Designing exercise and nutrition programs to promote normal weight maintenance for nurses. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing,19(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No03Man06

Vahey, D. C., Aiken, L. H., Sloane, D. M., Clarke, S. P., & Vargas, D. (2004). Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Medical Care, 42(2 Suppl), II57–II66. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000109126.50398.5a

Vertino, K. (2014). Effective interpersonal communication: A practical guide to improve your life. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 19(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No03Man01

Vidotti, V., Ribeiro, R. P., Galdino, M. J. Q., & Martins, J. T. (2018). Burnout syndrome and shift work among the nursing staff. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 26, e3022. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.2550.3022

Wisetborisut, A., Angkurawaranon, C., Jiraporncharoen, W., Uaphanthasath, R., & Wiwatanadate, P. (2014). Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occupational Medicine, 64, 279-286. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu009

World Health Organization. (2014, August). Mental health: a state of well-being. Retrieved from http://origin.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/