Ensuring that advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) students have optimal health promotion/disease prevention skills is critical as increasing numbers train and later work in rural and underserved areas. APRN students are more likely to have clinical training in rural areas in response to workforce initiatives designed to create a pipeline from nursing school to practice in rural and underserved communities. Therefore, they need both didactic and experiential learning to truly understand the social determinants of health in a community. We begin with a brief discussion about how APRNs meet needs in both rural America and women’s health. The article continues with an exemplar that considers how to prepare women’s health APRNs for a population in rural California. With the support of a rural consultant, a unique community assessment tool Mind Your Own Business was used by students to explore a new rural clinical placement area in southern California. We present the community assessment assignment and tool, analysis of student reflections; and subsequently identified community needs and offer future implications for education and practice. Nurse educators are encouraged to both enhance curriculum with activities to prepare students to work with rural populations, and expand clinical placements in these areas.

Key Words: advanced practice registered nursing, health promotion, community assessment, rural health, women’s health, nurse-midwives, Mind Your Own Business tool, Year of the Nurse and Midwife

Health promotion/disease prevention is the bedrock of advanced nursing practice...Health promotion/disease prevention is the bedrock of advanced nursing practice and therefore, an integral part of advanced practice nursing curriculum. Advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) students learn to use resources such as Healthy People 2020 and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Curley, 2016; APTR, 2015) to learn principles of population and community-based health, followed by data searches to identify the social determinants of health in a community. True understanding of the impact of such attributes on the community’s health is only partially uncovered by such learning. Lacking is the human, experiential element that resides in the life of the community. Therefore, it is critical to engage nursing students in community exploration activities to fully understand the health disparities and the strengths of the community (Evans-Agnew, Reyes, Primomo, Meyer, & Matlock-Hightower, 2017).

APRN students... may not be prepared to respond to the attributes of persons in their clinical placementsAPRN students are well positioned for such community activities as they apply refined versions of previously acquired interview skills and medical/nursing didactic knowledge. Master’s prepared nurses are educated to “Design patient-centered and culturally responsive strategies in the delivery of clinical prevention and health promotion interventions and/or services to individuals, families, communities, and aggregates/clinical populations” (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2011, p.25). In their careers as registered nurses, APRN students will likely have cared for vulnerable persons in the communities of their workplaces, but may not be prepared to respond to the attributes of persons in their clinical placements (Nyamathi, 1998). For example, APRN students are more likely to have clinical training in rural areas in response to workforce initiatives designed to create a pipeline from nursing school to practice in rural and underserved communities (Johnson, 2017).

In 2019, the Executive Board of the World Health Organization (WHO) designated 2020 as the "Year of the Nurse and Midwife" (WHO, 2019). This article will describe a new rural-academic partnership in California in a significantly underserved area that serves as one illustration of why nurses exemplify this designation. This partnership was strengthened when women’s healthcare women’s health APRNs used a unique community assessment tool to experientially learn about the rural community prior to their first clinical placement. The genesis of the community assessment tool used in the assignment, the Mind Your Own Business tool, will also be described by its author Dr. Juliana Fehr, the project rural consultant. We present the community assessment assignment and tool, analysis of student reflections; and subsequently identified community needs and offer future implications for education and practice.

APRNs Meet Needs in Rural America

...access to care continues to be the key factor in overall poorer health in rural areas as compared with metropolitan centers.Bolin et al., (2015) noted that access to care continues to be the key factor in overall poorer health in rural areas as compared with metropolitan centers. Health differences span the life trajectory from higher rates of infant prematurity to shorter adult life expectancy secondary to substance use/abuse, suicide, and cardiovascular disease and its comorbidities (ACOG, 2014b; Anderson et al., 2019; Singh & Siahpush, 2014). Access issues related to physical constraints (e.g. terrain, weather, and transportation) are often not modifiable in rural areas. However, the access issue related to deficit of healthcare providers is modifiable and emerging data describes that APRNs are gradually addressing this deficit.

Nurse practitioners (NPs) are the largest and fastest growing group of non-physician providers in the United States ([U.S.] Auerbach, Staiger, & Buerhaus, 2018; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2016a). This is evident in the average annual growth of healthcare providers from 2010 to 2016; physicians (1.1%), physician assistants (2.5%) and NPs (9.4%) (Auerbach et al., 2018). In the same time period, the number of NPs in primary care in the US doubled (59,442 to 123,316) while the number of primary care physicians was relatively constant (225,687 to 243,738). Further, the NP supply was highest in rural areas (41.3 per 100,000 population), as compared to urban (35.5) and metropolitan (37.9) areas (Xue, Smith, & Spetz, 2019). The proportion of non-physician healthcare providers in rural America also favors NPs. From 2008 to 2016, there was a 43.2% increase in NPs (17.6 to 25.2%) while physician assistants (PAs) showed no significant change (13.0 to 14.4%) (Barnes, Richards, McHugh, & Martsoff, 2018).

Recruiting registered nurses who come from the rural community, or similar communities, is better for long-term APRN retention However, approaches that can increase recruitment of health professionals to rural areas include short-term rural clinical placements, and curriculum tailored to rural practice (Gluck, 2017; Johnson, 2017). Therefore, nurse educators are encouraged to not only expand clinical placements in rural areas, but to enhance curricula with activities to prepare students for placements in these areas.

APRNs Meet Women’s Health Needs

The current supply of women’s health providers in the US in rural and metropolitan areas is insufficient to meet the demand. One study suggested that the demand will grow nationally at a modest 6% rate over the next decade (Dall, Chakrabarti, Storm, Elwell, & Rayburn, 2013). However, the projected demand will require more APRNs (certified nurse-midwives [CNMs] and NPs) trained in women’s health as the supply of physicians who specialize in obstetrics and gynecology (OB-GYN) diminishes due to: a) an unchanged number of OB-GYN residents trained since 1980 (about 1,205 residents per year); b) a greater proportion choosing subspecialties (19.5% in 2012 compared to 7% in 2000), leaving fewer to provide primary care OB-GYN services; and c) the higher proportion of female OB-GYNs (>50% now and >60% in 2022) who are more likely to work part-time schedules and retire earlier than their male counterparts (Rayburn, 2011).

The current supply of women’s health providers in the US in rural and metropolitan areas is insufficient to meet the demand.Concurrent with the workforce growth and demand for primary care APRNs, positive trends are occurring in the use and supply of women’s health providers, specifically women’s health NPs and CNMs. An increase in the supply of women’s health NPs and CNMs is expected in the US by 2025; this will result in a surplus of 1,650 FTE women’s health NPs and 2,060 FTE CNMs (U.S. DHHSb, Health Resources and Services Administration, & National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, 2016). In the context of the anticipated women’s health service deficits, it is estimated that the decrease in OB-GYN physicians will be at least partially addressed by anticipated surpluses.

Diminishing obstetric services in U.S. rural areas is a critical subset of the rural health access crisis.Diminishing obstetric services in U.S. rural areas is a critical subset of the rural health access crisis. As of 2014, less than half of rural counties offered obstetric services, even though three of four rural women depended on those local birth services (Kozhimannil, Henning-Smith, Hung, Casey, & Prasad, 2016). As compared to rural counties with obstetric services, initial studies show increases in infant mortality, preterm birth, and out of hospital birth in counties that have lost obstetric services (Kozhimannil, Hung, Henning-Smith, Casey & Prasad, 2018; Powell, Skinner, Lavender, Avery & Leeper, 2018). Women and newborns in rural areas are negatively affected not only by loss of place to give birth, but also the lack of obstetric providers.

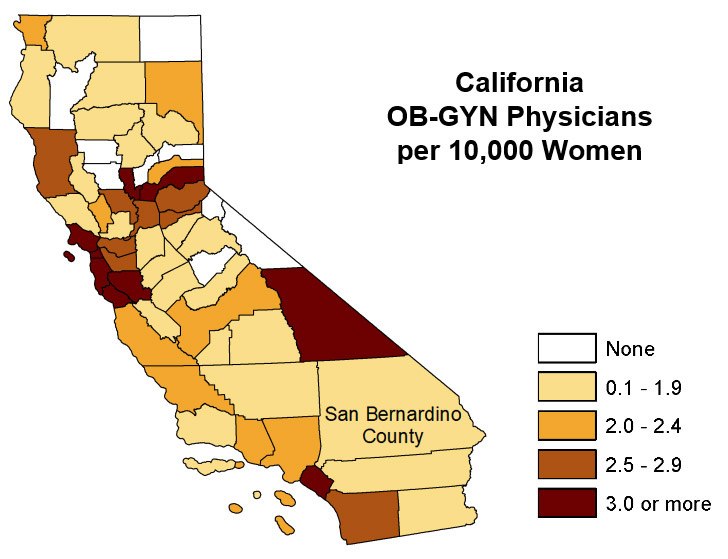

The impact of decreasing supply of OB-GYN physicians will be particularly dire in certain states, such as California.The impact of decreasing supply of OB-GYN physicians will be particularly dire in certain states, such as California. California’s female population is the largest in the US and is expected to increase by 22.61% by 2030 while the total U.S. female population is expected to increase by 17.76% (ACOG, 2014a). In California, the number of OB-GYN physicians in practice (3.95 per 10,000 for women of reproductive age) is lower than the national median (4.2 per 10,000). Nine of California’s 58 counties do not have any OB-GYN physicians (ACOG, 2014a) and 24 counties have fewer than two OB-GYNs for 10,000 women (Figure 1). One of the 24 counties is San Bernardino, the largest county in the United States. This county covers over 20,000 square miles of land, has 24 cities and towns, and multiple unincorporated communities. San Bernardino County has three distinct geographical areas: a valley, a desert region, and a mountain region (Figure 2). The location of the rural clinical placement described in this article was in one of the San Bernardino mountain communities, Lake Arrowhead (The Community Foundation, 2011).

Figure 1. Number of OB-GYN Physicians per 10,000 Women in California Counties

(ACOG, 2014a; used with permission)

Figure 2. San Bernardino County with its Valley, Mountain, and Desert Regions

(San Bernardino County, 2007; used with permission)

The United States is experiencing the prodrome of a maternity care paradigm shift.The United States is experiencing the prodrome of a maternity care paradigm shift. In contrast to other industrialized nations (e.g., England, Sweden, Netherlands, Norway) with midwife-centric maternity care models, the U.S. model is physician-centric. However, U.S. policy makers, healthcare systems, and consumers are heeding high-level evidence of better perinatal outcomes and lower costs when midwives are more accessible and central to care (Attanasio, Alarid-Escudero, & Kozhimannil, 2019; Ten Hoope-Bender et al., 2014; Vedam et al., 2018).

Even in states like California, where CNMs experience greater practice restrictions compared to almost all other states, the number of births attended by CNMs between 2007 and 2017 rose, while the number attended by physicians declined. In 2017, CNMs attended 10.5% of births in California, with more than 97% occurring in hospitals (Kwong, Brooks, Dau, & Spetz, 2019). Current efforts to accurately identify birth attendants in California are underway and preliminary results indicate that the actual percentage of CNM attended births in California is higher than 10.5% (California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, 2019). These trends suggest that while women’s health APRNs (i.e., women’s health NPs and CNMs) are increasingly meeting the greater demand for women’s health services in California, they ideally should also be prepared to meet the needs in California’s rural areas.

Exemplar: Preparing Women’s Health APRNs for a Population in Rural California

California State University, Fullerton, is a large, publicly funded university in Southern California that is part of a 23-university state system. “Cal State Fullerton” (CSUF) focuses on attracting and retaining first generation students; is designated as a Hispanic-Serving Institution; and is highly diverse, with 44% of students identifying as ethnic minorities (California State University Fullerton, 2019). The Fullerton School of Nursing has pre- and post-licensure undergraduate, credential, and graduate (master’s and doctoral) nursing programs. The Women’s Health Care concentration is a dual track master’s degree that allows students to concurrently become women’s health NPs and CNMs (CSUF School of Nursing, 2019).

In July 2017, CSUF School of Nursing Women’s Health Care Concentration (CSUF SON WHC) initiated a project, Rural Women of the Mountains Accessing New Services (Rural-WOMANS), in response to the Advanced Nursing Education Workforce Program (ANEW) (HRSA-17-067). This project expanded the Women’s Health Care Concentration by establishing a new academic-service partnership with Mountains Community Hospital and Rural Clinics (MCH) in the San Bernardino Mountains. Students have immersive clinical experiences at MCH in the rural mountain community of Lake Arrowhead and a previously established partner in an underserved area of downtown Los Angeles.

Beyond establishing the new academic-rural partnership, the two-year project objectives included: a) increasing the availability and breadth of women’s health services in the rural health clinic; b) admitting eight additional students, with at least two rural-based students seeking APRN education; c) converting Women’s Health Care courses to online delivery and enhancing WHC content across the curriculum relating to cultural competency, rural healthcare, mental health, health literacy, substance use/addiction, and telehealth and d) distributing traineeships to students who successfully completed 3-6 month immersive clinical experiences in rural or underserved areas.

Rural Health Consultant Prepares Faculty and Students

In the initial phases of developing the Rural WOMANS partnership, a rural health consultant, Juliana Fehr, CNM, PhD, FACNM, suggested content and activities to prepare faculty and students for practice in a rural health setting. Using her tool, Mind Your Own Business, students gathered experiential data about a rural community prior to their clinical rotations the following semester. We identified and analyzed themes from student reflections related to “rurality.” The assignment has been foundational for the activities that CSUF WHC students and faculty do in partnership with Mountains Community Hospital and Rural Clinics to improve access to women’s health services. In the following section, Dr. Fehr offers a narrative sharing the history behind her tool.

My sudden realization that an ounce of prevention was worth a pound of cure caused me to change my career to nurse-midwifery...Dr. Fehr’s Narrative (included with permission). As a rural health consultant with California State University, Fullerton Campus, I was thrilled to share my Community Needs Assessment Tool, Mind Your Own Business, developed in 1998, with graduate women’s health and midwifery students (J. van Oolphen Fehr, personal communication, August 13, 2017). The tool culminated from a long journey that I began as a special education teacher in Appalachia, teaching multiply handicapped children in a small schoolhouse deep in Virginia’s southwestern mountains. My sudden realization that an ounce of prevention was worth a pound of cure caused me to change my career to nurse-midwifery so that I could teach pregnant women to take care of themselves to increase their chances to give birth to healthy infants. Seven years later I was a CNM. I practiced for fourteen years in rural homes and a rural hospital. I spent another twenty years as the co-founder and director of a nurse-midwifery program focusing on increasing access to midwifery care in rural areas.

...I quickly learned that my “reductionist” thinking was not enough. As a clinician in the 1980s I entered women’s homes and hospital clinics, confident that my practice was “safe” because I followed research findings. However, I quickly learned that my “reductionist” thinking was not enough. During those long days and nights caring for laboring women, I developed a deep respect and admiration for those I cared for and I saw how dependent I was on them, their families, and their social networks to do my work. Being something of an enigma I found myself being embraced by rural communities who invited me to radio and television interviews, and to school, university, church, governmental, and other community meetings. I learned early that to truly care for women, I belonged next to them at their kitchen tables, offices, places of worship, gardens, baptisms, graduations, bar mitzvahs, and schools.

An unintended consequence of my caring was that I found myself a recipient of their caring.An unintended consequence of my caring was that I found myself a recipient of their caring. Indeed, caring was a two-way street. When I became their spokesperson in our state’s capital, they surrounded me with their safety nets which ultimately made it possible for me to start the midwifery program to serve their communities. In my early years, when I first arrived in my communities, many thought a “midwife” was a potentially dangerous person. But after experiencing midwifery care, many began to tell me stories of how years ago their mothers and grandmothers called the local midwife whenever a family member was sick. At that time a midwife was their only access to care. Many years later, they stood by my side as my colleagues and I convinced legislators that midwifery care continues to be essential to a family’s health.

Organically, over time, I also saw that my community assessments were taking on the structure of my individual assessments. This Community Needs Assessment Tool grew from many years of patiently and persistently networking, communicating, and listening. As a lifelong learner I began to see myself, and those I cared for, as reflections of our communities. Truth be told, I saw communities influencing and caring for individuals, and individuals influencing and caring for their communities. Organically, over time, I also saw that my community assessments were taking on the structure of my individual assessments. Indeed, visualizing communities through the lenses of their residents guided the structure of my assessments into similar categories as those of an individual female assessment; demographics; family and medical histories through systems approaches; menstrual, pregnancy and contraceptive histories, and social histories fell into remarkably similar categories. Also, my physical examinations (or community explorations) helped me gain a “physical feeling” of a community through which I could gain a deeper understanding of its residents.

By acknowledging that individuals and their communities reflect each other, my assessment tool opened a new awareness that guided me to effectively balance my research findings and a community’s demographic data, with an understanding of an individual woman’s preferences, values, and concerns. The community-individual dyad were the pieces of the puzzle that made my assessments holistic, complete and yet dynamic. This viewpoint allowed my expertise to grow by leaps and bounds. My clinical judgement and decision-making were positively affected by this worldview, which would later become the three-fold definition of evidence-based practice: an integration of the best research evidence with a clinician’s expertise which includes internal evidence from the data gleaned from a woman, while paying attention to a woman’s/family’s preferences and values (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019).

It is imperative that healthcare be provided together with patients, their families, and if needed, their networks. As a clinician I developed this worldview of evidence-based practice on the ground, with the people. As a midwifery educator, I mentored my graduate students into this discovery through my Community Needs Assessment tool. I am honored to share it with others.

Community Assessment Assignment

All the Women’s Health Care Concentration students at CSUF take the course Health Promotion/Disease Prevention prior to their first clinical rotation. The course is concurrent with the foundational course content colloquially known as the “3Ps” (i.e., pathophysiology, pharmacology, and physical health assessment). Of note, in Part I of the assignment, the tool follows the model of a systematic advanced physical examination while the students learn to an individual assessment in a separate course. In Part 2 of the assignment, the class is divided in four groups of 3-4 students. Each group receives a portion of the assessment (e.g. family and past medical history, menstrual/pregnancy history). The assignment is summarized briefly in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The Mind Your Own Business Community Assessment Assignment with Rubric

Community Assessment (Part 1)

This is a two-part assignment that involves individual and group work. Some aspects of the assignment will require field work (i.e., you will not be able to find the needed information via internet searches). Your field work assignment will in an area designated in the Community Assessment Tool.

This first part of the assignment is to be done individually.

|

Criteria |

Points Possible |

Points Achieved |

|

1. Demographic information

|

10 |

|

|

2. Scholarship: Logical and concise writing, APA/grammar |

5 |

|

|

Total Points Possible: |

15 |

|

Community Assessment (Part 2)

The second part of the assignment will be done within your and presented by your group. Note: there must be evidence that all persons in the group participated in the field work.

|

Content |

Points Possible |

Points Achieved |

|

1. Content appropriate to the topic; communicates pertinent information from community assessment guide |

10 |

|

|

2. Effective presentation – well-organized and within time limits |

2 |

|

|

3. Utilizes media appropriately; creativity |

2 |

|

|

4. Responds appropriately to questions and comments |

2 |

|

|

5. Collaboration evident |

2 |

|

|

6. Scholarship – APA references, citations in presentation, grammar/spelling |

2 |

|

|

Total Points Possible: |

20 |

|

Assignment Evaluation

As part of the final examination for the course, students complete two short-answer reflection questions:

- Based on course readings and your personal experience, what are the area’s greatest needs in terms of health promotion and disease prevention?

- What did you learn during the community assessment that will inform how you provide care for women and families in rural areas?

We used qualitative content analysis to identify themes from the written responses to these prompts. Responses were collated, coded, and codes were collapsed into themes. The next section discusses our findings.

Results

Following IRB approval, 14 students completed the Mind Your Own Business Community Assessment assignment and the process of sharing their findings with classmates. In the short answer reflection prompts, they described the community as “close knit.” For example, students often found it difficult to obtain what they considered to be public knowledge, such as the number of marriages, until the community came to know them. One student said, “being able to meander the streets, observing what the people dress like, how they communicate, and how they act was paramount for understanding how best to meld into the community.” For students who had only lived in urban areas, the experience was a “big culture shock.”

In response to the first prompt, students identified five community needs: a) access to health services; b) women’s health services and prenatal care; c) mental health; d) substance abuse; and e) preventive health and health screening. Community needs were understood within the context of “down the mountain.” As San Bernardino is the closest access to care if resources were unavailable “on the mountain,” “down the mountain” is, at best, a 40-minute drive on a curvy mountain road. The road can be icy during snow season thus, the drive can take several hours each way. Mountain Transit makes four trips “down the mountain” each day at a cost of $15 round trip. The fare is sometimes difficult for individuals working part-time and/or earning minimum wage.

Access to Health Services. Students identified three issues that could decrease access to health services: lack of insurance, lack of providers, and transportation. Many community members are employed seasonally and do not have health insurance, are not eligible for Medi-Cal (California’s form of Medicaid), or may be unaware that Medi-Cal is available. They also may not be able to access services or transportation outside their hours of work.

The community hospital has an emergency room physician, one full-time surgeon, a part-time orthopedic surgeon, and two primary care physicians who only see patients with private insurance. There are three family NPs in the Rural Clinic for those without insurance or with publicly funded insurance (MediCal, Medicare). Care for other health issues must be accessed down the mountain. However, many community members do not have cars or reliable transportation, thus, rely on intra-community buses or daily bus service down the mountain which may not allow them to easily get to and from appointments. In addition, residents who do not live close to established bus routes have difficulty getting to bus stops during inclement weather.

The only women’s health service available on the mountain is a routine pap smear.Lack of Women’s Health Services/Prenatal Care. “I learned that there are not a lot of prenatal care/women’s healthcare... Since there are no OB-GYN providers, women would need to go down the mountain in order to get care. The teen pregnancy rate is also high.” The only women’s health service available on the mountain is a routine pap smear. All prenatal and postpartum care is down the mountain, and women in labor are often fearful they will not reach the facility in time. One school nurse covers many schools and is unable to provide reproductive education to students. Only oral contraceptives and condoms are available on the mountain. Teens wanting oral contraceptives often fear they will be “found out” by parents or do not have transportation to access providers. Students also found it was culturally acceptable to be a teen mother in this population.

Mental Health. Healthcare providers reported that approximately two-thirds of the patients seen at the community hospital have significant mental health needs. Behavioral health services are available daily using a telehealth service at the rural health clinic. Residents wishing to access this service often lack consistent transportation and frequently miss appointments.

Substance Abuse. Providers note a high incidence of individuals with substance abuse, primarily crystal methamphetamine and alcohol. Residents display drug-seeking behaviors during provider visits, although the clinic has a well-developed protocol for prescribing pain medications. There are few resources on the mountain, such as health education. Students noted that intimate partner violence was often a side effect of substance abuse, and that women in relationships with substance abusers were at high risk for homelessness due to this violence.

Preventive Health and Screening. Students found that patients often lacked knowledge of their bodies, appropriate health behaviors, and lifestyle recommendations. This is not surprising as there is no public health department in the area, and the county health department does not provide service on the mountain. Students do not receive health education in schools and there are limited sources of health education on the mountain other than those provided to MCH patients. For reasons previously mentioned, such as lack of transportation or financial issues, residents may be unable to access preventive health screening or routine check-ups through MCH clinics or facilities down the mountain. As noted, residents face various barriers to knowledge about health, access to health services, and understanding of preventive health practices

Students stated that residents were protective of their community, thus they had to know the community, provide holistic care, and educate patients. Findings that Informed Future Care.In response to the second prompt, students were asked how their experience of the community assessment and working in a rural community would inform their future care to women and their families. Students stated that residents were protective of their community, thus they had to know the community, provide holistic care, and educate patients. They described this as being “private” or “guarded” and not providing information to those not part of the community. In addition, residents often did not go beyond the norms of the community.

Based on this, students identified four actions they would take in their future practice. The first was establishing a trusting relationship prior to assessing or examining patients. This involved entering the relationship with an attitude of respect; dressing and speaking in a way that was not intimidating; learning what was important to the patient and family; and asking about their needs. Establishing and maintaining this rapport was fundamental to providing quality care.

Holistic care also involved determining the level of support for recommended health behaviors and making recommendations consistent with community norms.In addition to knowing the patient, the second action was knowing about the community. Examples of required knowledge were available services; the range of living conditions; “the high incidence of domestic violence and drug use;” transportation; socioeconomic factors; and community norms.

The third action was providing holistic care. This was described as “care of the whole person, not just what you see.” They needed to learn about health habits within the individual or family context, provide care without judgment, make it as easy as possible for the individual or family to access available resources, be diligent about screening for health of the living situation, and be sensitive to barriers such as transportation issues. Holistic care also involved determining the level of support for recommended health behaviors and making recommendations consistent with community norms.

...students understood that education must be provided in the context of a reciprocal relationship. Last, students understood that education must be provided in the context of a reciprocal relationship. Patients would teach them about their lives and health needs and providers would educate the patient and family. It would require additional time to cultivate the trusting relationship, determine the patient’s perspective and needs, and provide information that might be new to the patient. Students also noted the importance of providing education and resources to teens about contraception and sexually transmitted diseases.

Future Implications

The community assessment assignment using the Mind Your Own Business tool has become an ongoing part of the CSUF Women’s Health Care Concentration Health Promotion Disease Prevention course. To date, the area for community assessment has been in the single location of our rural partner. However, the option of doing the assignment in another partner area in an underserved urban area of Los Angeles is also being considered. This assignment is one that could be revised for undergraduate nursing students in their community health rotation; is applicable to other APRN graduate program populations (e.g., family, adult, pediatrics, gerontology); and could be adapted for non-APRN master’s and doctoral students as well. In this instance, the students were learning about our new rural partner to prepare for their clinical placement in the rural health clinic. However, the assignment can be adapted to prepare nursing students for clinical rotations or projects in any vulnerable/marginalized population.

...our adult learners themselves addressed the imperative that course projects such as this continue in order to meet the needs of our rural communities...As described, our adult learners themselves addressed the imperative that course projects such as this continue in order to meet the needs of our rural communities, regardless of the type or foci of health profession chosen. Just as Dr. Fehr learned as she immersed in rural life, rural residents are protective of their communities, and if practitioners take the time to know about, and immerse into, the communities they work in, they will be embraced and welcomed into the reciprocal relationships necessary for teaching and learning. From these relationships holistic knowing of a community grows and teaching can become more tailored to the unique needs of each individual within the context of that community.

Conclusion

In rural areas, where access to women’s health and maternity services is shrinking, women’s health NPs and CNMs are needed more than ever.APRN students need not only classroom content, but experiential tools. The community assessment described here helps them to, in the words of Dr. Juliana Fehr, “gain a ‘physical feeling’ of a community to gain a deeper understanding of its residents” (J. van Oolphen Fehr, personal communication, August 13, 2017). The planning, implementation, and results of such a rural community exploration have been presented here to show one example of how women’s health APRNs gathered their own information to prepare for a new rural clinical experience. In rural areas, where access to women’s health and maternity services is shrinking, women’s health NPs and CNMs are needed more than ever. In 2020, the designated Year of the Nurse and Midwife, we encourage educators to incorporate similar activities and field work in curriculum to improve care in rural communities, and deepen the student appreciation of the community that they will serve.

Author Note: To access the Mind Your Own Business: A Community Needs Assessment Tool please contact Juliana van Olphen Fehr, CNM, PhD, FACNM at the Shenandoah University Nurse-Midwifery Program, Winchester, Virginia, U.S.A. E-mail: jfehr@su.edu.

Acknowledgement: This program, Rural Women of the Mountain Accessing New Services (Rural WOMANS), was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), as part of an award totaling $1,541,000 with no percentage financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. HRSA Advanced Nursing Workforce Education Grant no. T94HP30890

Authors

Ruth Mielke, PhD, CNM, FACNM, WHNP-BC

Email: ruthmielke@fullerton.edu

Dr. Mielke is the Principal Investigator for the Health Resources and Services Administration Advanced Nursing Workforce Education Grant no. T94HP30890 “Rural Women Accessing New Services” (Rural WOMANS) and coordinates the Women’s Health Care Concentration at the California State University School of Nursing. She practices as a nurse-midwife/women’s health nurse practitioner at Eisner Health, a federally qualified health center in Los Angeles, California and at the Rural Health Clinic at Mountains Community Hospital in Lake Arrowhead, California.

Sue Robertson, PhD, RN

Email: srobertson@fullerton.edu

Dr. Robertson coordinated the Nurse Educator Concentration at California State University Fullerton (CSUF) for nine years. She is Emeritus faculty in the CSUF School of Nursing.

Juliana van Olphen Fehr, CNM, PhD, FACNM

Email: jfehr@su.edu

Dr. van Olphen Fehr, is a retired professor-emeritus, and was the co-creator and director of the first nurse-midwifery education program in Virginia at Shenandoah University where she developed the “Midwifery Initiative,” a series of collaborative agreements with universities serving rural areas to enable graduate nursing students to obtain their nurse-midwifery education through Shenandoah University while attending these universities. While directing the nurse-midwifery program, she was appointed by Virginia’s Governor The Honorable Mark R. Warner to a Rural Obstetrical Services Task Force where she co-created legislation (HB2656) to establish pilot midwifery clinics in medically underserved areas.

References

ACOG. (2014a). ACOG Workforce fact Sheet: California. Retrieved from http://california.midwife.org/california/files/ccLibraryFiles/Filename/000000000290/CAACOGworkforce2014revised.pdf

ACOG. (2014b). Committee Opinion No. 586: Health disparities in rural women. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 123(2 Pt 1), 384. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000443278.06393.d6

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011). The Essentials of Master's Education in Nursing. Retrieved from Washington, D.C.: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/MastersEssentials11.pdf

Anderson, B., Gingery, A., McClellan, M., Rose, R., Schmitz, D., & Schou, P. (2019). NRHA policy paper: Access to rural maternity care. National Rural Health Association Policy Brief. Retrieved from https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/NRHA/media/Emerge_NRHA/Advocacy/Policy%20documents/01-16-19-NRHA-Policy-Access-to-Rural-Maternity-Care.pdf

APTR (2015) Clinical prevention and population Health Curriculum Framework, version 3. Retrieved from: https://www.teachpopulationhealth.org/uploads/2/1/9/6/21964692/revised_cpph_framework_2.2015.pdf

Attanasio, L. B., Alarid-Escudero, F., & Kozhimannil, K. B. (2019, November 3). Midwife-led care and obstetrician-led care for low-risk pregnancies: A cost comparison. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1111/birt.12464

Auerbach, D. I., Staiger, D. O., & Buerhaus, P. I. (2018). Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians — Implications for the physician workforce. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(25), 2358-2360. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1801869

Barnes, H., Richards, M. R., McHugh, M. D., & Martsoff, G. (2018). Rural and nonrural primary care physician practices increasingly rely on nurse practitioners. Health Affairs, 37(6), 908-914. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1158

Bolin, J. N., Bellamy, G. R., Ferdinand, A. O., Vuong, A. M., Kash, B. A., Schulze, A., & Helduser, J. W. (2015). Rural Healthy People 2020: New decade, same challenges. The Journal of Rural Health, 31(3), 326-333. doi:10.1111/jrh.12116

California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. (2019). Maternal Data Center. Retrieved from https://www.cmqcc.org/maternal-data-center

California State University Fullerton. (2019). Boilerplate Information. Retrieved from https://www.fullerton.edu/doresearch/resource_library/boilerplate_information.php

California State University Fullerton School of Nursing. (2019). Nursing Programs at CSU Fullerton. Retrieved from http://nursing.fullerton.edu/programs/index.php

Curley, A. L. (2016). Introduction to population-based nursing. In A. L. Curley & P. A. Vitale (Eds.), Population-based nursing: Concepts and competencies for advanced practice (2nd ed., pp. 1–22). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Dall, T. M., Chakrabarti, R., Storm, M. V., Elwell, E. C., & Rayburn, W. F. (2013). Estimated demand for women's health services by 2020. Journal Of Women's Health, 22(7), 643-648. doi:10.1089/jwh.2012.4119

Evans-Agnew, R., Reyes, D., Primomo, J., Meyer, K., & Matlock-Hightower, C. (2017). Community health needs assessments: Expanding the boundaries of nursing education in population health. Public Health Nursing, 34(1), 69-77. doi:10.1111/phn.12298

Gluck, M. E. (2017). What are effective approaches for recruiting and retaining rural primary care health professionals? Rapid Evidence Review. Retrieved from https://www.academyhealth.org/publications/2018-01/rapid-evidence-review-what-are-effective-approaches-recruiting-and-retaining

Johnson, I.M. (2017). A rural "Grow your own" strategy: Building providers from the local workforce. Nursing Administration Quarterly October/December, 41(4), 346-352. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000259

Kozhimannil, K. B., Henning-Smith, C., Hung, P., Casey, M. M., & Prasad, S. (2016). Ensuring access to high-quality maternity care in rural America. Women's Health Issues, 26(3), 247-250. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2016.02.001

Kozhimannil, K. B., Hung, P., Henning-Smith, C., Casey, M. M., & Prasad, S. (2018). Association Between Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services and Birth Outcomes in Rural Counties in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 319(12), 1239-1247. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.1830

Kwong, C., Brooks, M., Dau, K. Q., & Spetz, J. (2019). California's midwives: How scope of practice laws impact care. In California Health Care Foundation (Ed.). Retrieved from https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/CaliforniasMidwivesScopePracticeLawsImpactCare.pdf

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: A guide to best practice (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

Nyamathi, A. (1998). Vulnerable populations: A continuing nursing focus. Nursing Research, 47(2), 65-66.

Powell, J., Skinner, C., Lavender, D., Avery, D., & Leeper, J. (2018). Obstetric care by family physicians and infant mortality in rural Alabama. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM, 31(4), 542. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.04.170376

Rayburn, W. (2011). The obstetrician–gynecologist workforce in the United States. Washington DC: American Congress of Obstetricians.

San Bernardino County. (2007). San Bernardino County Land Use Services Department, 2007 General Plan. California State Association of Counties. Retrieved from http://wp.sbcounty.gov/indicators/county-profile/

Singh, G. K., & Siahpush, M. (2014). Widening rural–urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969–2009. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(2), e19-e29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017

Ten Hoope-Bender, P., de Bernis, L., Campbell, J., Downe, S., Fauveau, V., Fogstad, H., . . . Van Lerberghe, W. (2014). Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. The Lancet, 384(9949), 1226-1235. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60930-2

The Community Foundation. (2011). San Bernardino County 2011 Community Indicators Report. Riverside, CA: The Community Foundation. Retrieved from: http://www.sbcounty.gov/uploads/dph/publichealth/documents/2011-Community-Indicators-Report.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, & National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. (2016a). National and regional projections of supply and demand for primary care practitioners: 2013-2025. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/primary-care-national-projections2013-2025.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, & National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. (2016b). National and regional projections of supply and demand for women’s health service providers: 2013-2025. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Retrieved from https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/womens-health-report.pdf

Vedam, S., Stoll, K., MacDorman, M., Declercq, E., Cramer, R., Cheyney, M., . . . Powell Kennedy, H. (2018). Mapping integration of midwives across the United States: Impact on access, equity, and outcomes. PLoS ONE, 13(2), e0192523. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192523

World Health Organization. (2019, January 30). Executive Board designates 2020 as the “Year of the Nurse and Midwife.” Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/hrh/news/2019/2020year-of-nurses/en/

Xue, Y., Smith, J. A., & Spetz, J. (2019). Primary care nurse practitioners and physicians in low-income and rural Areas, 2010-2016. Journal of the American Medical Association, 321(1), 102-105. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.17944